[Speaking Truth To Power: Commentary]

Yesterday, as some readers recall, after I was informed that an assistant Queens County district attorney told the judge in the Kris Gounden trial that he planned to call me as a witness, I tweeted “Hope DA is not trying to prevent Black Star News from #speakingtruthtopower and writing about the #Goundencase.”

I’ve been writing about what I’ve called a 12-year vendetta against Gounden by police officers from the 106 precinct and the Queens County DA’s office since 2012. On every occasion, I’ve reached out to the DA’s office for comment while writing about Gouden’s cases over the years, including the pending matter in Queens criminal court arising from a Feb. 5, 2018 incident. As I’ve previously reported, Gounden’s ordeal began soon after his family purchased a home in Howard Beach in 2007 as shown in a New York Daily News story at the time. His was the first family of color to move into his new neighborhood.

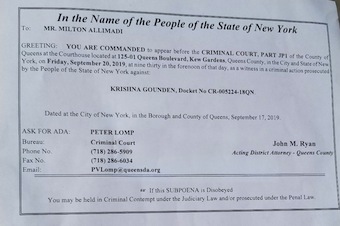

Today, it turns out that my journalistic instincts with respect to the assistant district attorney’s motive was correct. During a break in Gounden’s trial, assistant district attorney Peter Lomp handed me a subpoena. He wants me to take the witness stand on Friday morning. What did he want to discuss? The conversations between defendant Gounden and myself.

“You mean during the course of my reporting, correct?” I inquired.

“There will be no tricks. I will ask you direct questions about those conversations,” Lomp said.

“No problem,” I said.

Lo and behold when the trial resumed this afternoon, just before he delivered his opening statement Lomp, asked Judge Eugene Guarino who is handling the case to have me removed from the courtroom since he would be calling me on the witness stand. Gounden’s attorney, Ron Kuby, objected, telling the court he didn’t see on what grounds Lomp was seeking to have me removed: after all, I was publisher and editor of Black Star News and I’d been writing consistently about the case; and, there was also a First Amendment rights issue.

Judge Guarino also seemed puzzled by Lomp’s request. I was not a witness to the alleged incident underlying the case. After the judge denied Lomp’s request, he withdrew it.

It’s no secret that I’ve written about a pattern of arrests of Gounden dating back years from officers from the NYPD’s 106 precinct and the subsequent court proceedings; they have not occurred in a historical vacuum. Readers can read a number of those articles that places this pending case in some perspective by Googling “Gounden and Queens District Attorney.”

Today I will focus on what the two sides –Lomp for the prosecution and Kuby for defendant– said by summing their opening statements.

Lomp told the jury that on Feb. 5, 2018, Joseph Adorno, who was allegedly a victim of a hit-and-run by Gounden, drove his wife Evaline Orovco, to Manhattan for a medical appointment from their Queens home. When the couple drove back to Queens, they eventually encountered Gounden at a Queens red light near 117 Street and Rockaway Blvd. Adorno was driving his wife’s black BMW; Gounden, in his vehicle ahead, was distracted. He was holding his cell phone up against his windscreen as if he was recording something outside.

Gounden drove forward and stopped his car in the middle of a crossroads. Adorno drove pass Gounden. He was heading to a nearby auto repair-shop called V.J.’s to have the BMW checked out; on the way back to Queens Adorno had encountered a pothole. When Adorno exited his car, he could see that Gounden was driving forward, still with his phone pressed against the windshield. Gounden, still distracted, then struck Adorno as he was crossing the road. Lomp said Adorno braced himself with the windscreen of the vehicle. As Adorno’d body shifted, he was struck in his back by the side-view mirror of the vehicle and he stumbled and fell. Gounden didn’t stop; he fled from the scene of the incident.

Adorno got into his car and told his wife to dial 911; they drove after Gounden. Orovco instead used her cell phone to video-record Gounden’s vehicle as it sped away. Gounden, according to Lomp, led Adorno and his wife on a wild goose chase. Eventually, he pulled up at an address that turned to be the home of his grandmother, where he sometimes lived. Meanwhile the couple had used Adorno’s cell phone to dial 911 — because Orovco’s own phone died after recording the chase; she’d been playing games on the phone earlier and burned up energy. The couple made their 911 call at around 2:26 pm –which was also around the time Gounden made the first of his own two “self-serving” 911 calls, Lomp said. Why did Gounden make the calls? Because he wanted to give the false impression that it was he –not Adorno– who’d been the victim of an assault. (Gounden made his second 911 call at 2:34 pm.)

The police arrived and heard both sides’ account of the incident. One officer, Carlos Bello, took Orovco’s dead phone to his car and powered it. After he viewed the video he then arrested Gounden. At the time he was arrested Gounden also did not have a driver’s license in his possession and his New York driving privileges had been suspended. He’d not paid an administrative fine by DMV even though a notice had been mailed to another Queens address listed as his home. Adorno was transported by ambulance to Jamaica Hospital where he was x-rayed. When he was told it could take as long as eight to 10 hours to read the result –as there were many more urgent cases ahead– Adorno decided to leave after 2 1/2 hours.

Lomp allowed that jurors may find that Adorno may not be the “smartest guy” they’ve ever met. He allowed that even though on Feb. 5, 2018, the day of the incident, the couple was “happily” married with two children, since then, the couple separated. They may end up getting divorced. Lomp told jurors that during an argument, Orovco told Adorno that she was prepared to tell the authorities that he was lying about the allegations against Gounden. Lomp also allowed that Adorno had been arrested for allegedly assaulting his wife and that, just two days ago, pled guilty to disorderly conduct. His wife had obtained an order of protection. None of these issues were to suggest that Adorno was not telling the truth concerning the alleged crime committed by Gounden. Lomp also told jurors that race had nothing to do with the arrest and prosecution of Gounden, who is a dark-skinned ethnic Indian immigrant from Guyana.

Gounden’s lawyer Ron Kuby, opened by telling jurors that Adorno had an “anger management” problem. Adorno no longer had access to his wife’s BMW, and a $500-a-week job she’d provided him. All he’d been required to do was not to lay a hand on his wife; this was something he couldn’t resist not doing. (Orovco has said Adorno punched her; Adorno himself claims he only “pushed” her.)

Adorno seemed to be in a big hurry on the day of the Feb. 5, 2018 alleged incident. He had been tailgating the car Gounden was driving in Queens; he was so impatient that he tapped the rear of the vehicle. The car had Florida plates and belongs to Gounden’s mother; he lives with her in Florida. When Gounden drove forward, he pulled over to let Adorno pass by. Adorno drove ahead and eventually emerged from his vehicle and stood in the street. As Gounden drove by, Adorno banged on Gounden’s vehicle. As Gounden drove away, Adorno “escalates” the situation and drove after Gounden. Kuby ridiculed the notion that Gounden led Adorno on a wild chase. He said Gounden dialed 911 to report the incident. “He doesn’t know if it’s a crazy guy,” Kuby said.

Gounden returned to his grandmother’s home, from where he was subsequently arrested. Kuby noted that Adorno has since offered multiple, different, conflicting, and “irreconcilable” versions of the alleged incident; especially, when describing the nature of the injury he suffered. The narrative kept shifting depending on when and to whom he was describing the alleged injuries.

Adorno first told police he’d been injured on his hand by Gounden; later, while in the ambulance being transported to hospital, he claimed it was his back; later, Adorno said it was his shoulder; yet later, he signed a sworn statement that he was struck on his hand, not the side of his back. Later, when Adorno filed a claim against Gounden’s insurer and testified under oath to an Allstate lawyer, he claimed he was hit on the left knee, and that he also had neck injuries. More recently, in an effort at a pay day Adorno had filed a civil lawsuit against Gounden and his mother. This time Adorno claimed several injuries, including internal injuries; injuries to his ribs; and other injuries that may be permanent. Kuby also noted that on the day of the Feb. 5, 2018 incident Gounden did have a valid Florida driver’s license; and that he was not aware of the administrative fine by New York’s DMV. Kuby said the jurors would have to determine whether race played a role. However, unlike Lomp, Kuby didn’t explicitly rule it out. “I’m not here telling you race is not an issue,” he said.

Based on my coverage of this case, there are some critical information that Lomp left out of his opening statement. When Officer Bello and others responded from the 106 precinct, Gounden, who was wary about past encounters, made sure his cell phone audio recorder was running. Gounden’s surreptitious recording captured Orovco’s voice saying the couple had a video recording of the incident. Gounden could be heard insisting that Adorno and Orovco were lying about the existence of such a recording and he demanded, several times, that they play it. Instead, Gounden was told to turn around so he could be arrested. Gounden asked why he was being arrested. After the officer said “they said they have a video,” Gounden can be heard asking if the officer had seen the video, to which Bello responded, “No.” Still, Gounden was arrested. Bello’s own words in the recording –a copy of which I forwarded to the Queens DA’s office and to the NYPD headquarters when I was seeking comment– contradicts Lomp’s opening statement that Bello had powered Orovco’s phone and viewed the video before arresting Gounden.

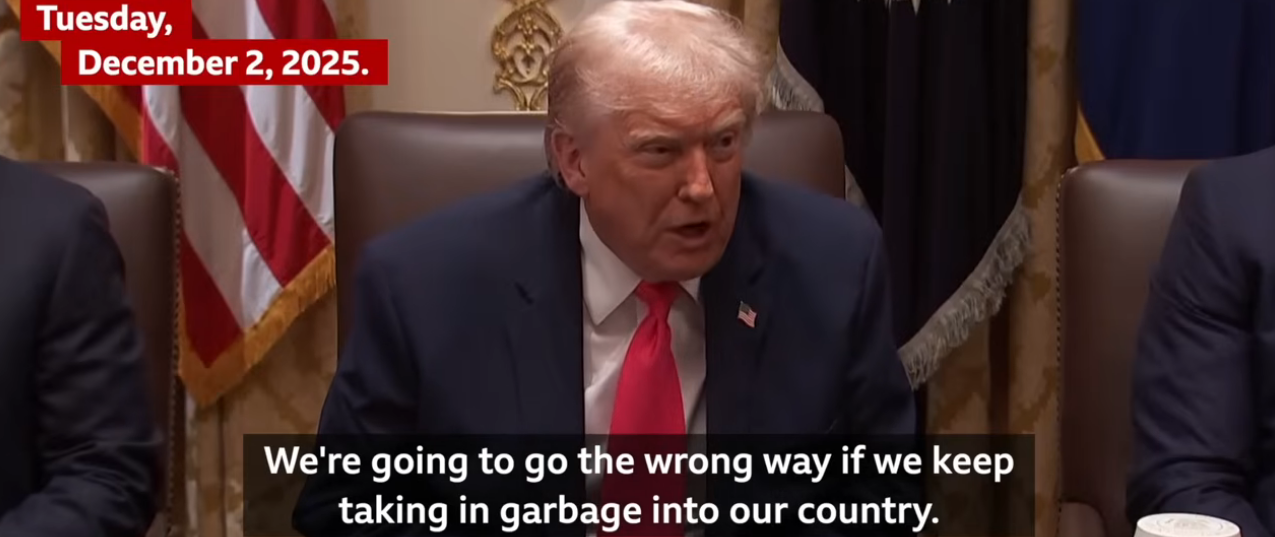

Even though Lomp in his opening told jurors that race hadn’t played a role, it was actually Adorno himself who apparently played the race card. In his sworn testimony to Daniel Gilley, the Allstate attorney on April 26, 2018 –the lawyer also questioned Adorno about numerous auto accident insurance claims he’s filed in the past–Adorno claimed there had been a “Black man” in the car with Gounden on that day of the Feb. 5, 2018 account.

Many readers must be familiar with this ugly “Black-guy-did it” calumny sadly pervasive in this country.