Photo: Twitter

The redrawing of congressional and legislative maps around the country has still yet to reach its midway point, but there already are some clear trends. These initial takeaways give some clues to what to look out for as the process continues.

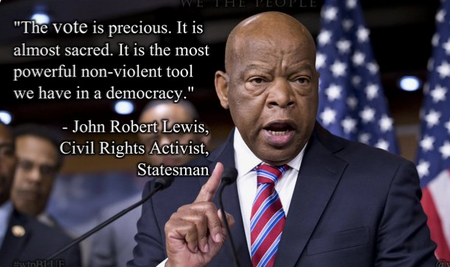

Most of these early trends, unfortunately, do not bode well for fair maps, and they provide more evidence of the need for state-level reforms and federal ones like the Freedom to Vote Act and the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act.

Gerrymandering is alive and well — with some differences.

Last decade saw some of the most extreme gerrymandering in U.S. history. But early signs are that this decade’s gerrymandering could in some ways be even worse. Last decade, Republicans were responsible for most of the extreme gerrymanders. This time round, both Democrats and Republicans appear ready to be aggressive, though Democrats will have far fewer opportunities than Republicans to draw skewed maps.

For Republicans, this decade’s gerrymanders so far have been a mixture of defense and offense. This contrasts with last decade, when Republicans aggressively targeted Democratic seats, taking advantage of the landslide majorities they won in the 2010 Tea Party midterms.

For example, Texas’s new congressional map is aimed largely at preserving the lopsided advantages Republicans already hold due to last cycle’s gerrymandering, a recognition perhaps of rapidly changing demographics and shifting political tides in the suburbs.

But not all Republican gerrymanders are defensive. In North Carolina, for example, Republicans are on offense, passing a congressional map that would eliminate 2 of 5 Democratic seats and that could give Republicans an 11 to 3 seat advantage in a strong GOP election cycle. And Republicans’ offensive posture this cycle could extend to smaller and medium-sized states — like Tennessee and Missouri — which did not see extreme gerrymandering last decade but where new maps could eliminate longtime Democratic seats in cities like Nashville and Kansas City.

By contrast, Democrats are more singularly in offensive mode this decade. In Illinois, for example, they passed a wildly contorted new congressional map that gives Democrats a 14 to 3 advantage in the state’s congressional delegation. And there is wide expectation that Democrats will be equally if not more aggressive in New York when the legislature takes up redistricting in early 2022.

But Democrats’ ability to level the playing field through gerrymandering is limited. That’s because the party controls the drawing of just 75 congressional districts this cycle compared to the 187 that Republicans control, and many of the seats that Democrats will draw are in states like Massachusetts or Rhode Island where Democrats already hold all the seats.

Communities of color are bearing the brunt of aggressive map drawing.

Unsurprisingly, communities of color are emerging as principal targets in this decade’s redistricting. But some of this decade’s maps are especially brazen in their treatment of communities of color

In Texas, for example, communities of color accounted for 95 percent of the state’s population growth last decade. Yet, not only did Texas Republicans create no new electoral opportunities for minority community communities, their maps often went backwards. In the Dallas-Fort Worth region, for instance, the most Latino congressional district in the region saw its Latino citizen voting age population reduced from 48 percent to 42 percent due to the move of a large block of Latino voters in suburban Dallas into a mostly rural district. Similarly, in North Carolina, the state’s new Republican-drawn congressional map significantly undermines the district of one of two Black members of the state’s congressional delegation.

And Republicans are not alone in targeting minority voters. In Illinois, Black voters have filed suit contending that Black voters were split among multiple districts in order to shore up white Democratic incumbents.

A combination of racially polarized voting and residential segregation have long made targeting the political power of communities of color an easy and ruthlessly effective way to change the partisan valiance of maps — regardless of whether map drawers are Democrats or Republicans. But this decade, the Supreme Court’s greenlighting of partisan gerrymandering and its decision to gut key provisions of the Voting Rights Act have made the targeting of communities of color easier than ever. Racially discriminatory maps now are likely to be defended on the basis of politics and, with no need to get federal approval under the Voting Rights Act, states no longer have any need to be cautious in drawing maps.

Maps may ultimately be struck down, but litigation will take years in many cases. All the while, states like Texas will continue to use discriminatory maps.

There will be fewer competitive seats when all is said and done.

Another victim of this decade’s maps will almost certainly be competition. If current maps are a harbinger of the rest of the redistricting cycle, the 2022 midterms will feature far fewer competitive districts.

Take Texas, for example. Last decade’s Texas map featured five to six seats that were competitive in a good Democratic year. Under the newly enacted map, no Republican-held seats are competitive. In fact, Democrats are not favored to win more than one additional seat unless they win close to 60 percent of the statewide vote — something that in the near term seems like a remote possibility.

Republicans are afraid of the suburbs.

For many decades, suburbs in states like Texas were a solid Republican heartland. No more. With half of all people of color in metro areas now living in the suburbs, and with white suburban voters trending Democratic in recent years, suburban voters now increasingly threaten GOP hegemony.

The result has been new maps like Texas’s that divide suburban communities and join them to heavily rural, and more reliably Republican, districts — a tactic that used to be used with Democratic cities like Austin but now is a tool for neutralizing suburban voters. The newly redrawn Texas 13th congressional district, for example, places parts of suburban Denton County (north of Dallas) in a sprawling district that stretches all the way to the Texas Panhandle.

Some redistricting reforms are doing well, but others aren’t.

Last decade saw states enact a record number of redistricting reforms. But evidence from this redistricting cycle suggests that not every reform is equally robust.

On the one hand, new independent commissions in Colorado and Michigan have done well in meeting the goals of reformers and producing fairer maps. In Colorado, maps passed by the commission and approved by the state supreme court have low rates of partisan bias as well as increase the number of competitive seats. In Michigan, the process is ongoing, but maps put out by the commission for public comment similarly all have negligible partisan bias (in sharp contrast to the gerrymandered maps drawn by Republicans in 2011). On the other hand, reforms that give a significant role in the process to partisan elected officials have struggled.

In Ohio, for example, where all members of the state’s redistricting commission are elected officials and Republicans hold 5 of 7 seats, the commission approved new legislative maps on a party-line basis that give Republicans a durable supermajority (several lawsuits are now challenging those maps). Likewise, in Virginia, where legislators make up half of the bipartisan commission, the process has broken down in acrimony and deadlock, sending responsibility for map drawing to the state supreme court (though the court process so far is playing out fairer).

There also are signs that new advisory bodies that draw maps for legislative consideration could end up being largely shunted to the side by partisan legislatures determined to gerrymander. In Utah, for example, the state legislature ignored a commission-recommended congressional map that would have created a competitive seat in Salt Lake City, and instead legislators passed one that aggressively divides the city among four districts in order to make all four districts safely Republican.

Something similar could play out in New York.

A full assessment of reforms will have to wait until the cycle is complete, but one clear, early lesson seems to be that, in a deeply polarized age, the degree to which partisan elected officials are allowed to continue to be involved in redistricting will play a key role in whether a reform delivers the intended results.