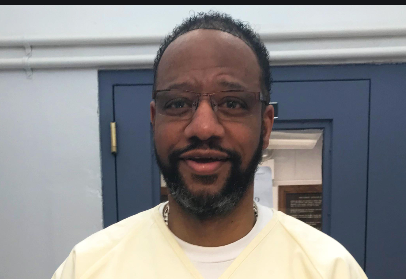

[Pervis Payne]

Selby: “There is still time to save Payne’s life…Payne’s family, legal team, and supporters are continuing to call for justice in his case, as Davis’ family continues to push for the truth and to end the death penalty.”

Photo: PervisPayne.org

Death Row inmate, and Innocence Project client Pervis Payne’s life now hangs in the balance–he is scheduled to be executed on Dec. 3 even though the evidence suggests he is just another wronfully convicted Black man.

On Sept. 21, 2011, the state of Georgia ended Troy Anthony Davis’ life with a lethal injection. Davis was executed for the murder of a police officer, a crime he always maintained he did not commit.

In the months before his execution, people around the country urged Georgia to reconsider in light of the serious doubts about his guilt, including the fact that seven out of nine witnesses recanted their testimony against him. Despite calls to stay his execution from politicians on both sides of the aisle, the NAACP, the Innocence Project, and Amnesty International, the State moved ahead with Davis’ execution.

On the morning of his scheduled execution, Davis asked Wende Gozan-Brown of Amnesty International to share a message with the world.

“The struggle for justice doesn’t end with me. This struggle is for all the Troy Davis’s who came before me and all the ones who will come after me,” he said.

Unfortunately, there have been several Troy Davis’s in the nine years since his execution, and the struggle for justice is far from over. Since 2011, dozens of men sentenced to death have been exonerated — most of them Black men wrongfully accused of murder — according to data from the National Registry of Exonerations. In fact, innocent Black people are seven times more likely to be wrongfully convicted of murder than innocent white people, the National Registry of Exonerations reported.

These wrongful convictions are just the ones that have been discovered. But it’s likely that many more people with claims of innocence are currently on death row, like Pervis Payne, a Black man living with an intellectual disability, who has been on death row in Tennessee for 33 years for the murder of a white woman, a crime he’s consistently said he did not commit.

Even though 21 states have now abolished the death penalty, those which continue to use capital punishment do so in ways that are inextricably linked to and exemplify the United States’ deeply rooted history of racism. A new report from the Death Penalty Information Center (DPIC) shows that the states with the highest incidences of lynchings of Black people between 1883 and 1940, are largely the same states that have executed the most Black people over the last 50 years.

Last year, 52% of people on death row were Black, though they comprise just 13% of the overall US population. This has little to do with the nature of the crimes Black people are accused of committing, and more to do with the racially biased way that the death penalty is applied.

Since 1977, when the executions resumed, just 21 white people accused of killing Black people have been executed, while 295 Black people accused of killing white people have been executed, even though white people make up only half of all murder victims, according to the Death Penalty Information Center.

“Racial disparities are present at every stage of a capital case and get magnified as a case moves through the legal process,” said Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, in a statement on the organization’s website. “If you don’t understand the history — that the modern death penalty is the direct descendant of slavery, lynching, and Jim Crow-segregation — you won’t understand why.”

Whether or not the death penalty is used is also frequently influenced by the race of the victim. A 2019 study found that people convicted of killing white people are executed at 17 times the rate of those convicted of killing Black people.

According to the report, both implicit bias and overt racism influence the use of the death penalty in the US with judges, jurors, experts, defense attorneys, and prosecutors, at times, exhibiting explicitly racially biased behavior. Such bias was seen in Payne’s trial, during which the prosecutor repeatedly referred to the “white skin” of the victim, a white woman named Charisse Christopher, while using racist stereotypes to portray Payne, a Black man, as a hypersexual and violent drug user, even though no evidence supported this characterization.

Payne is scheduled to be executed on Dec. 3. The Innocence Project, the Federal Public Defender for the Middle District of Tennessee, and the law firm Milbank LLP are fighting hard to save his life. Recently, the Shelby County Criminal Court ordered DNA testing of evidence in Payne’s case. This evidence has never been tested for DNA before, and the results could confirm what Payne has said for over three decades — that he did not commit this crime.

There is still time to save Payne’s life, though his life should never have been put on the line because his intellectual disability makes it unconstitutional to execute him. And while the state of Tennessee has never disputed Payne’s disability diagnosis, it provides no mechanism through which to demonstrate his diagnosis to the court. Last week, his legal team filed a complaint with the court, asking the State to stay his execution until he is able to show this diagnosis.

Payne’s family, legal team, and supporters are continuing to call for justice in his case, as Davis’ family continues to push for the truth and to end the death penalty, which has resulted in the death of innocent people. In his final moments, Davis asked God to have mercy on his executioners and beseeched his family to “continue to fight this fight.” Nine years later, the continued fight for justice is needed now more than ever.

By Daniele Selby