Mission accomplished for Gen. Sejusa? Whose side is he really on?

[Africa: Commentary]

The mission of United Democratic Ugandans (UDU) which was established in July 2011 at the Los Angeles conference and its action program approved at the Boston conference in October 2011 is inclusiveness in Uganda efforts to unseat the failed National Resistance Movement (NRM) government by non-violent methods.

We chose a non-violent strategy for three main reasons:

1. Change of regimes by violent means in Uganda has failed to produce the desired results in terms of peace, stability and human security (freedom from fear, freedom from want and freedom to live in dignity);

2. Violence begets violence as has been demonstrated in Uganda and makes matters worse. This conclusion is in line with John Horgan’s (2014) observation that “violence even in a just cause often causes more problems than it solves, leading to greater injustice and suffering. Hence the best way to oppose an unjust regime … is through nonviolent action. Nonviolent movements are also more likely than violent ones to garner internal and international support and to lead to democratic and non-militarized regimes”;

3. There is sufficient empirical evidence that “nonviolent struggles are steadily increasing in numbers whereas violent movements are decreasing [because Africa and the entire international community have discouraged them as a means of changing unjust regimes witness the cases of Mali, Central African Republic and Burkina Faso where the military was prevented from forming a government], and in recent decades nonviolent movements have outnumbered violent ones. Moreover, nonviolence is about twice as likely to be successful as violence” (John Horgan 2014).

Accordingly, against this backdrop UDU called upon Ugandans including especially those in the security forces and closer to NRM strategic institutions like the presidency to join hands with the civilian population as was done for example in The Philippines in 1986 to remove by nonviolent means the dictatorial regime of Ferdinand Marcos; Marcos once seemed immovable.

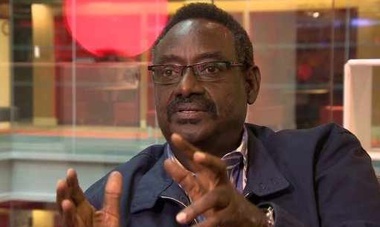

Thus, when Gen. David Sejusa and Bishop Zac Niringiye announced that they had joined Uganda political dissenters against the NRM regime they were warmly welcome. The articles written by Gen. Sejusa against the regime and the interviews on BBC and VOA and the demonstration undertaken by Niringiye and his subsequent brief detention gave prima facie evidence that they were serious about regime change.

I was an early critic and skeptic as many readers will recall.

What raised suspicions is that Sejusa did not say anything new; he also did not give names of those who had directly or indirectly contributed to the suffering of Ugandans. An invitation to have him on Radio Munansi was not accepted.

Efforts to talk with him on the telephone were equally unsuccessful. As a last resort I wrote an article raising issues that remained unanswered. The article was published in the New York-based Black Star News.

Upon receipt of the article The London Evening Post contacted Sejusa for his reaction before it was published. His unhelpful response was published and is available for easy reference.

Subsequently we were advised to contact Dr. Amii Omara-Otunnu then chair of Freedom and Unity Front (FUF) on matters related to the organization. Sejusa was presented as a game changer; and Sejusa openly advocated violence. This strategy of regime change by violent means posed a problem for UDU that is non-violent in the first instance.

However, in a subsequent conversation, Dr. Amii Omara-Otunnu and I agreed to work together on areas that did not involve violence such as issuing a joint communiqué about the anti-gay legislation. We didn’t issue the communiqué apparently because Dr. Amii Omara-Otunnu did not get clearance.

There was also a disturbing story that heightened suspicion. Apparently, Gen. Sejusa had asked some members of his group to contact Joseph Kony and his terrorist group to mount a joint invasion of Uganda and unseat the NRM government. Whispering spread that Sejusa was possibly on duty to dismantle the opposition in the Diaspora that was getting stronger and worrying the NRM regime.

Because of these developments we tried to ascertain that Sejusa was truly in exile and had severed relations with Museveni government. Sejusa declined to provide information to confirm that he had applied for and was granted asylum status and who was supporting him in the Diaspora. He also refused to answer questions relating to the allegation that had been made that he had received on a Swiss bank account $1 million from Museveni.

Relations between him and other Ugandans in the Freedom and Unity Front (FUF) deteriorated apparently on strategy issues and six months after FUF’s inauguration in London the organization disintegrated as announced by Gen. Sejusa himself. Sejusa was deserted en masse; he remained with few friends.

Sejusa’s abrupt return home has given rise to many interpretations. Some are saying that his mission failed; others say he in fact fulfilled the goal he set out to accomplish; and yet others say he was broke and winter was too much for him, forcing his return to Uganda.

However, his arrival at Entebbe airport in the middle of the night might signal that the authorities didn’t want him to talk. Or his return could signal a political calculation by NRM that it is tolerant of political dissent and is therefore “democratic” and respectful of individual freedoms and rights. This could all be intended for the consumption of the international community as 2016 elections approach — Museveni may also be under some pressure not to seek re-election in 2016.

A few days upon arrival in Uganda Sejusa renounced violence against the regime. This could also mean that if he had entered into a deal with some Ugandans in the Diaspora to unseat Museveni government by force he was sending a signal that he had netted them and they should abandon the project or face consequences.

The case of Zac Niringiye is equally intriguing. There are rumors that Zac is still doing business with the NRM regime and that he still travels on a diplomatic passport.

Another observation that raises suspicion is that while on mission abroad Zac resists to be interviewed or photographed. And his exact mission has been difficult to understand except that he is against “Musevenism” which he has declined to define.

At The Hague conference of November 2013 participants from Uganda and in the Diaspora agreed to block the 2016 elections through nonviolent actions. To that effect it was agreed that a roadmap be prepared together with methods to conduct non-violent resistance.

However, upon return to Uganda instead of embarking on blocking elections Zac began to mobilize for electoral reforms in preparation for the 2016 elections contrary to The Hague decision.

To cap it all, the emerging consensus is that Sejusa and Niringiye are helping the NRM to address the mounting challenges against the regime at home and in the Diaspora.

The mobilization for electoral reform is to divert attention from preparing the opposition for the 2016 elections. Are Sejusa’s and Niringiye’s missions abroad intended to dismantle the opposition that is exerting influence thanks in part to social media and diplomatic networking?

For more information contact erickashambuzi@yahoo.com or visit www.kashambuzi.com