Columnist believes quick change could be triggered in Uganda by event such as Gen. Museveni’s purported scheme to have his son Brig. Muhoozi Kainerugaba, shown, replace him

[Comment]

When I read a disturbing story about political developments in Burkina Faso that appeared in AfricaWatch of September 2014, I contacted a Burkinabe to find out what was happening.

Without hesitation, he responded categorically that Burkina Faso was neither Tunisia nor Egypt and there was nothing to worry about.

After the people’s revolution sent former President Blaise Compaore into exile, I contacted a fellow Ugandan and wondered whether Uganda’s Yoweri Museveni might be next. He laughed and reminded me that when Uganda opposition tried to mimic what happened in Egypt the demonstrators were given a lesson they will never forget. Accordingly, Uganda is neither Egypt nor Burkina Faso. And there was nothing to worry about.

When the anti-Mubarak regime demonstrations began following the successful people’s revolution in Tunisia, the political leaders in Cairo quickly announced that “Egyptian is not Tunisia”, meaning that it was not in danger because of historical and cultural factors and its political system and geopolitical role. Notwithstanding, the Egyptian people triumphed and Mubarak was ousted from power.

A closer look at other revolutions including in Ethiopia in 1974, in Iran in 1979, in the Philippines in 1986 and now in Burkina Faso reveals that the people’s power is always underestimated. In all these cases there was a fallacy that the strong security forces and international support would not allow people’s revolutions to succeed.

In Iran, for example, shortly before the Shah went into exile in 1979, he had been advised that for at least ten years he had nothing to worry about.

Similarly, Ferdinand Marcos called a snap presidential election in the belief that he would win. When the fraudulent election results were announced and the people rejected them he went ahead with inauguration plans hoping his security forces and international backers would protect him. He was wrong. The Filipino people triumphed and Marcos ended up in exile.

Because of space constraints, I will use Tunisia to show that contrary to popular belief that everything was fine, there were signs of trouble which had been ignored. The government and some reporters focused on the fallacy of elections and economic growth and per capita income figures to hoodwink the public at home and abroad that Tunisia was peaceful, stable and prosperous.

In December 2010, the very month that trouble began, an article praising Tunisia was published in New African. The author wrote that Tunisia “is a country at peace with itself. Peace in the sense of stability; the stability that gives a country the time and space to plan and implement its plans: the kind of implementation that leads to a balanced national development”.

He added that “The social, economic and political developments under Ben Ali have been simply phenomenal. First, he abolished the existence of presidency-for-life in the country and welcomed the creation of multi-party democracy. Since then elections have been held in 1989, 1994, 1999, 2004 and 2009”. Regarding the economy the author showed that “Per capita income has increased from 960 dinars in 1986 to 4,847 dinars in 2008”. He concluded that “Tunisia is a breath of fresh air – in a region and continent choked by political, economic and social impurities. Long may it prosper”.

However, after the Tunisian revolution had occurred, another writer visited the country to find out what had happened. He learnt that there had been problems all along that had been ignored. He reported his findings in NewAfrican of February 2011 “But while the ‘Jasmine Revolution’, as it has been termed, was seemingly sudden, it is widely known that there has been an uneasy calm brewing in Tunisia for a number of years”.

In 2008 there were demonstrations in Gafsa that the authorities had suppressed. In 2010 there were the Ben Guardane demonstrations against the closure of the border with Libya where communities from both sides of the border conducted informal trade. And chants at football stadiums against the ruling elite were used to demonstrate frustrations of the ordinary people.

Despite success stories in terms of regular elections and rising per capita incomes many Tunisians were unhappy especially about political repression and unemployment. Until Mohamad Bouazizi, an unemployed graduate of 26 years set himself on fire and died a few days later, “Tunisians had often been considered to be passive, easily contented, happy with their fate and their way of life”. Therefore the sudden uprising took everyone by surprise. This happened because the suffering overcame fear and summoned courage to challenge the oppressive regime of Ben Ali. Are there similarities between pre-revolutionary Tunisia and Uganda today?

Since Museveni launched structural adjustment program in 1987 and allowed elections to be held every five years since 1996, Uganda has been presented as a peaceful, stable, secure and democratic country with rapid economic growth and per capita income on its way to becoming a middle income country and society.

However, beneath the rosy picture there is a lot of suffering including from acute hunger, unemployment and under-employment, sprawling urban slums largely as a result of adverse economic factors pushing people out of the countryside, widening inequalities and their demonstration effects and suppression of opposition leaders and their supporters.

Demonstrations that were quickly suppressed have occurred including against the fraudulent elections of 2011. Thus, Uganda seems ready for a revolution. What is missing is a trigger to set it off. In the case of Tunisia it was Mohamad Bouazizi while in Burkina Faso it was Blaise Compaore’s desire to amend the constitution that sparked the revolutions.

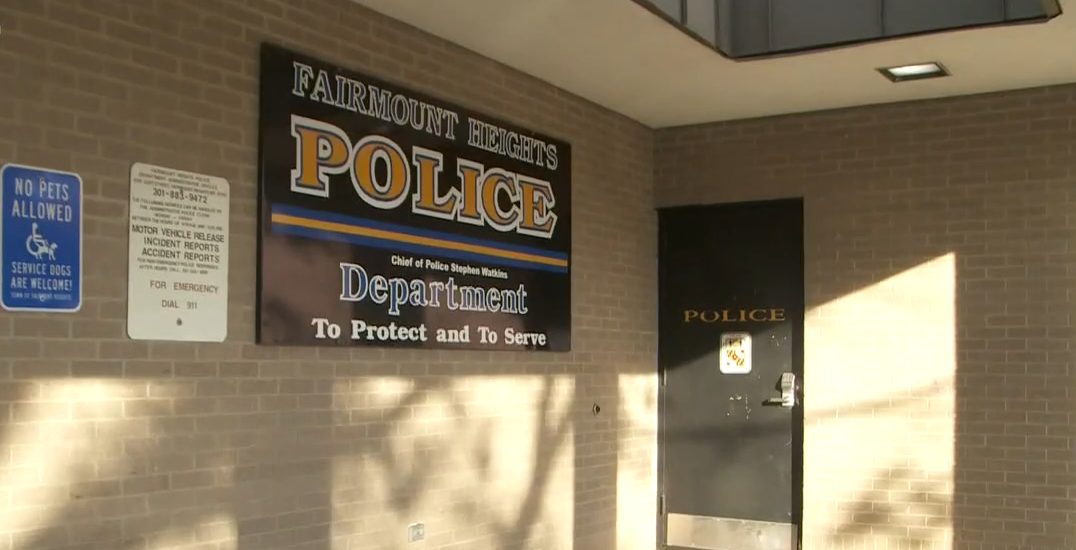

In Uganda it could be Museveni’s desire to make his son Brig. Muhoozi Kainerugaba the next president.

Eric Kashambuzi is New York-based international consultant on development issues.