Aguirre says No More Deaths has filed several claims about abuse of migrants in detention only to see agents cited in the claims in the field again or to be told that an agent was transferred rather than disciplined. “That lack of accountability goes hand in hand with the lack of transparency,†Aguirre says.

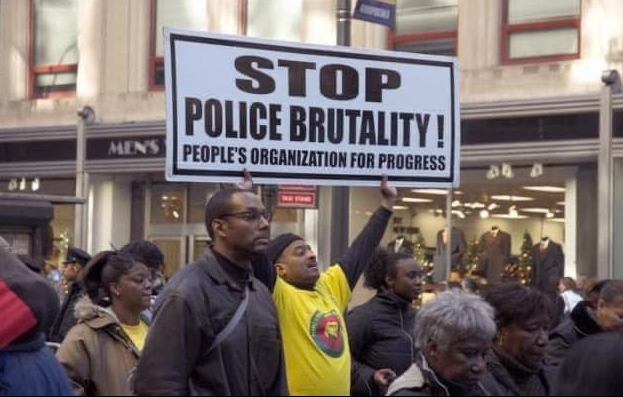

Victims of police brutality typically remain in the public consciousness long after cases that made them famous fade from the airwaves and headlines.

Rodney King, Oscar Grant and Sean Bell will forever be remembered as symbols of police abuse. Rarely, however, does the public hear about men, women and children who have been abused or killed by U.S. Border Patrol agents.

Human rights activists contend that these agents aren’t held accountable for their actions because they are part of the Department of Homeland Security, a designation that seems to give them a license to operate outside the law. Some agents administer a brand of frontier justice that would not be tolerated in metropolitan areas or if their victims were white, rather than usually Latino.

Many victims are undocumented immigrants, who may be unwilling to tell their stories because they fear reprisal. Still, immigrant rights advocates say it’s critical that the mainstream media chronicle border violence so Border Patrol agents are held accountable for their actions. The media also must humanize people who have life-altering encounters with the agents.

“In the Latino community, a lot of us know children who wake up in the morning and have shotguns placed in their faces by one of President Obama’s ICE agents,” says Roberto Lovato, cofounder of presente.org, a Latino advocacy group. He was referring to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Lovato notes that a record number of deportations, about 400,000, have occurred since Obama took office in 2009, double the number during George W. Bush’s administration.

Furthermore, the Los Angeles Times recently reported that the number of ICE agents assigned to spot and deport undocumented immigrants has jumped by 25 percent. Aggressive efforts to deport undocumented immigrants result in more frequent encounters between people in border regions and ICE agents. Some of these encounters have been deadly.

Presente.org is raising awareness about the death of Anastasio Hernández-Rojas, 42, near San Diego, Calif., in 2010. The undocumented immigrant died after being detained by Border Patrol agents in the United States near San Diego, where had lived since he was a teenager. He was beaten and shocked with a stun gun.

The agency has not made public names of agents involved in the attack on Hernández-Rojas or punished them, leading Presente.org to call for a thorough investigation by the U.S. Justice Department. The site says more than 30,000 people have signed its online petition to the department. Presente.org credits PBS for investigating Hernández-Rojas’ killing and finding that the Border Patrol may have covered up pertinent details of his death, a revelation it aired in a documentary last month.

John Carlos Frey, a documentary filmmaker, reported on the incident for an investigation produced by the PBS news program “Need to Know” in partnership with the Investigative Fund at the Nation Institute.

In the Los Angeles Times, he wrote, “Hernandez lived and worked in San Diego for more than 25 years, raising his five U.S.-born children. In May 2010, in the process of being deported for being undocumented, Hernandez was severely beaten and shocked with a Taser and killed. The segment features new video from witnesses who watched as Hernandez, handcuffed and lying on the ground, was surrounded by about 20 border officials.”

The San Diego coroner’s office, Frey wrote, “classified the death as a homicide. As a result of the brutal beating, Hernandez suffered a heart attack. An autopsy also revealed several loose teeth; bruising to his chest, stomach, hips, knees, back, lips, head and eyelids; five broken ribs; and a damaged spine.”

While various media outlets reported on Hernández-Rojas’ death at the time, PBS stands out as the one that took the Border Patrol to task and released new footage of the beating.

The circumstances of Hernández-Rojas’ death is not an anomaly. “Over the past two years, there have been eight cases of Border Patrol killing people in questionable circumstances,” Lovato says. None of the deceased have become household names, which Lovato blames partly on lack of media interest in such cases.

He says that while Spanish-language news outlets consistently cover brutal treatment of migrants, the English-language press “has a history of ignoring Latino pain and suffering.”

Lovato says racism and public perceptions about undocumented immigrants are factors.

“We kind of have a constant struggle with the media,” says Adam Aguirre, media liaison for No More Deaths, a migrant advocacy group based in Arizona. “The media is complicit in the narrative that Border Patrol is part of Homeland Security, so they should be given a little bit of extra latitude of doing what they have to do.”

But Aguirre balks at the idea that such latitude should include abuse of migrants. Last August, No More Deaths released “A Culture of Cruelty,” a report citing “interviews detailing more than 30,000 incidents of abuse and mistreatment” involving the Border Patrol. The group wants the Border Patrol held accountable when agents use excessive or deadly force and to be more transparent with the public about its procedures.

Representatives of human rights groups such as the Women’s Refugee Commission in New York say that even when they file Freedom of Information Act requests with the Border Patrol, much of the material they’re given is blacked out.

Aguirre says No More Deaths has filed several claims about abuse of migrants in detention only to see agents cited in the claims in the field again or to be told that an agent was transferred rather than disciplined. “That lack of accountability goes hand in hand with the lack of transparency,” Aguirre says.

Aguirre says he hopes that the media will take an interest in nonviolent strategies he says Border Patrol agents use to deter migrants from crossing the border, such as allegedly destroying water bottles his organization leaves in the desert for them.

“We find human remains, people who are in dire medical condition,” Aguirre says. “For us, a water bottle is a life, and when Border Patrol destroys water bottles, for us that’s tantamount to murder. We’re going to be focusing on that this summer because the media likes to hear stories about being people being denied food and water.”

While the mainstream media may not extensively cover cases of alleged Border Patrol abuse, the public does seem to take interest. Like presente.org’s petition, one by No More Deaths on change.org has garnered thousands of signatures.

Gabriela Garcia describes herself on change.org as a “global volunteer, immigrant rights advocate and freelance writer . . . blogging” on the site, which allows the public to petition policymakers about issues of concern. “I think there’s a lot of concern around Border Patrol issues,” Garcia says. “I think we’ve seen, and not just this year but last year, a huge rise in petitions around deportations and stopping deportations. We’ve seen a big rise.”

Public interest in these matters may not lead to more comprehensive media coverage. Michelle Brané, director of the Detention and Asylum program at the Women’s Refugee Commission, says a major obstacle she has encountered in reaching out to the media is that journalists want faces to go with their stories.

“They want to talk directly to the victim,” she says. “They want to get the victim on camera, which is really difficult in these cases. That’s because victims and their family members, especially if undocumented, are too fearful to go on camera.”

Brané also says the mainstream media may hesitate to cover border concerns more comprehensively because they want to tell stories that generate public sympathy and because many Americans don’t view abuse of migrants as a problem.

“I think there is the sense that it’s the border and that they’re ‘illegal,’ ” she says. “There’s this view that they aren’t supposed to be there, and they put themselves in the situation. Whatever happens to them they deserve. It’s hard to get sympathy or garner outrage over some of these cases.”

http://mije.org/mmcsi/criminal-justice/media-must-carefully-scrutinize-abuses-us-border-patrol