R. Donahue Peebles

The Man Who Would Be New York City Mayor

Multi-millionaire real estate developer R. Donahue Peebles’ vision of New York is of “a tale of one city” — a city where everyone gets an equal opportunity, as he puts it.

As mayor, Peebles says he’d make sure that every community — every ethnic group, had equal access to good education for their children, equal protection of and respectful conduct from the police, access to affordable housing for those earning between 30k and 50k and with families, and most importantly access to the multi-billions of dollars that New York city spends with private companies.

In the just-ended fiscal year, out of $17 billion spent with private contractors, New York City spent merely three-tenths of one percent with African American vendors and six-tenths of one percent with Latino vendors. “If we can’t get a fair share of business from our own government where can we get it from?” Peebles asks.

To say that Peebles, an African American who dropped out of pre-med and went on to build a real estate empire, is disappointed with Mayor Bill de Blasio would be an understatement.

He says he considers the mayor a friend and that he supported him during his mayoral campaign and got other business executives to back him. But how quickly things can change in two years. Peebles says he’s now seriously considering a run himself in 2017.

He says he ‘s already met with key church and community leaders; he’s conducted several interviews, and he plans a series of town hall meetings in every borough. Unlike mayor de Blasio’s recent townhall, his will be open to the public and not by invitation, Peebles say.

“The mayor has been dishonest,” Peebles says, especially when it comes to increasing how much of the city’s annual $17 billion budget for purchases with vendors goes to Black-, Latino- and Women-owned business, which he says de Blasio had promised would grow to 20%.

Peebles says it would have been better if de Blasio said the problem was challenging and would take time, or if he’d said it wasn’t a priority issue for his administration, rather than saying spending with Black and Latino companies had grown by 50% under his administration.

“What he’s saying is instead of a crumb, we’re now getting a crumb-and-half,” Peebles says. “I find that insulting to us, condescending to us, arrogant and dishonest.”

A spokesperson for Mayor de Blasio didn’t respond to an e-mail message seeking comment today.

Peebles says the template for creating a Black middle class in New York and African American wealth already exists. He’s enthusiastic when discussing the “transformative” powers of government. There’s no reason why New York City’s chief executive can’s accomplish here what mayors Maynard Jackson and Marion Barry were able to do in Atlanta and Washington, D.C., respectively. “With mayor Barry he just said he wouldn’t sign off on any contract that didn’t include 35% African American involvement; and in Atlanta it started with the airport,” Peebles says, referring to mayor Jackson’s own condition that African American vendors get at least 25% of the contracts.

Barry helped “create the strongest Black middle class in America; and he also created Black wealth.”

In Washington, D.C., when Barry was elected mayor in 1978, only 3% of city contracts were going to African American-owned businesses. By the time he was into his second term, about 50% of the contracts were going to Black-owned businesses, Peebles says.

In New York, the social and economic woes, including the violence, that afflict African American communities are directly linked to the lack of opportunities from the City to create employment and wealth, Peebles says. “Given an opportunity we can compete, we can solve the problems in our communities,” he says.

Combine the lack of opportunity to earn income and create wealth with the abysmal conditions in the education system, African Americans remain trapped in a cycle of impoverishment.

The schools are so bad that students graduate high school with eighth-grade reading levels. Those who are even less talented than the ones that graduate are unemployable, he says.

The degradation in some African American neighborhoods –as a result of the denial of opportunity and through neglect– is akin to putting a gun in the hands of someone who wants to harm the community, Peebles says.

Peebles excoriates the mayor for demonizing charter schools. He says conditions in the schools are so terrible that charter schools must be a part of the solution with public schools, which should be infused with more resources. “There are 100,000 students in charter schools and 100,000 waiting to get in,” he says. “The mayor has taken the side of the teachers union against the kids.”

Peebles says even the mayor’s proposal for affordable housing was “spin” because he’s addressing the needs of people who make on average $130,000, not those with families and who earn $30,000 or $50,000 and are in desperate need of affordable housing, he says.

He says there are creative ways developers can work with the City to create affordable housing for families in the lower income range. In return the city could offer incentives such as use of other City land for commercial use. “The private sector is not going to do something which doesn’t make business sense,” he says.

Peebles mocks de Blasio’s contention that the City had just come off one of its safest summers pointing out that when he said that, 23 more people had already been killed compared to last year. “The relatives of those killed don’t think it’s been safe,” he said, also noting the incident where Carey Gabay, 43, the Harvard-educated aide to Governor Cuomo was shot dead by an unknown assailant

“Our community is less safe,” under mayor de Blasio, Peebles says. “And the crimes have become even more random.”

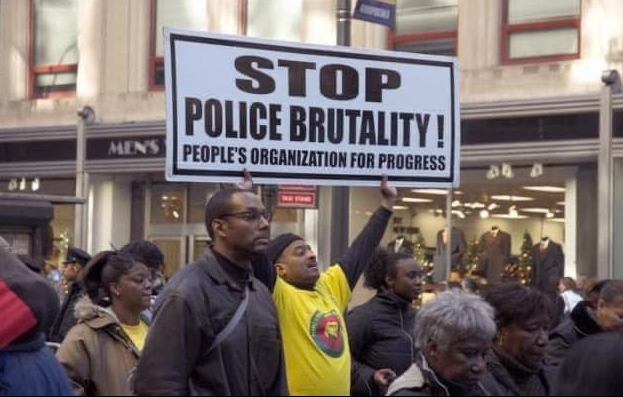

“African American and Latino communities bear the disproportionate burden of crime,” in New York City, he says. “African Americans are as anti-crime as any other community. We deserve to be protected and served by the police.” And while the mayor points to a reduction of stop-and-frisk statistics, African Americans were still victims of aggressive policing.

Seated in a mini-suite for the interview, in his large 16th-floor corner office with a spectacular view of Central Park, Peebles speaks with confidence — the self assuredness of a man who enjoys professional and financial success, and more. He’s on top of the news and reels of stats as he discusses the city’s economy, the lack of diversity, the schools and the policing.

Peebles developed his work ethic while working as a boy with his father who was a mechanic, in Washington, D.C,, where he grew up.

Both his paternal and maternal grandfathers were from the South where segregation was law of the land. Both instilled in their children -including Peebles’ father– the idea that “the American dream” was attainable, Peebles says.

Peebles’ father saw action and was wounded in Korea. In addition to working with his father he also volunteered to work on City Council races and met Marrion Barry when he was 14. After Congress passed Home Rule Act in December 1973 Washington became eligible to elect its mayor directly; previously the City had been under the control of Congress.

In 1978 Barry was elected mayor.

Peebles who by then was a pre-med student at Rutgers, quit and returned to D.C. He tried real estate sales but interest rates were at 20% and it was hard to qualify buyers; Peebles became an assessor and also worked with his mother who was in the industry.

Barry thought highly of Peebles and appointed him on a 15-member Board of Equalization, that heard appeals of property tax assessments. One year later, at 24, he became it’s chair. “I was the youngest sub-cabinet level appointee in the City’s history,” he recalls.

Peebles proved his maturity quickly. He appointed the older real estate professional who had also vied for the job, as his deputy. Peebles said he wanted people from the grassroots to have access to the board — large companies always hired attorneys to file their appeals.

So he started workshops in every council district where residents were taught how to fill the forms to appeal assessments when warranted.

Peebles’ break as a developer came in 1986. He won a development project in what was then the rundown Anacostia section of Washington, which had never recovered after the riots following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

The City, under mayor Barry, pre-leased office space, which allowed Peebles to get financing deal from a bank. That project was worth $10 million and it became part of many others that helped revitalize the Anacostia area which now boasts offices of several major institutions and government agencies. “That was my first break; and it was that break that helped launch me,” Peebles, says.

Today, the Peebles Co. handles a portfolio of properties and development projects valued at about $3.5 billion. Forbes magazine estimates Peebles’ own networth at $700 million. He was a major donor and fundraiser for both Bill Clinton and Barack Obama — he’s also a member of Obama’s National Finance Committee.

In addition to D.C., and New York, his business now operates in Miami, in Boston, in Las Vegas, and in California.

Peebles recalls that when he first started considering New York as a destination for his business, he was shocked by the lack of African American entrepreneurs in the real estate industry. “They just weren’t there,” he says.

He said he’s determined to help transform the City.

Mayor de Blasio’s main problem was that he never acknowledges that there’s a problem and prefers to “spin” because he’s a political strategist.

Peebles says he’s concluded that de Blasio isn’t serious when it comes to dealing with the lack of diversity in vendors working with the City; the schools; affordable housing; and policing.

As mayor, Peebles says he would address the contracting issue by appointing a deputy commissioner as well as an inspector who would review all contracts to enforce diversity.

He would also split up large contracts, such as those for $500 million, into many smaller contracts –maybe $50 million– so smaller-sized firms could meet the bonding requirements. The companies could then later collaborate on projects.

“I would appoint the best and most qualified individuals,” to all positions, Peebles says, adding that William Bratton’s appointment as police commissioner was strategic–political calculation by de Blasio who wanted to send a message to a “certain constituency” that he was “tough on crime.”

Asked whether he wouldn’t miss running his company if elected mayor Peebles says he has a son, R. Donahue Peebles III, who’s been working parttime at the company and will soon be able to devote more time when he graduates from Columbia; in addition to the employees onboard. Peebles, who is 55, is married to Katrina, and in addition to the son, has a daughter, Chloe.

Peebles says he had overlooked de Blasio’s inexperience in running a large budget like New York’s $60 billion. He’s free to “hold the mayor accountable” because his company isn’t seeking any business from the City.

“I thought he would hire the best people,” Peebles says, of the mayor.

“I believed him. He was dishonest,” he says.

A spokesperson for the mayor didn’t respond to an e-mail message requesting comment by publication time.