Photo: Inequality.org

As with many issues raised by this pandemic, the problem of hazard pay is fraught with deep, multiple inequities. Like the compensation that traditionally remunerated particularly dangerous work in such fields as military service, mining, or construction, hazard pay was introduced early in the pandemic to recognize the risks and dangers that frontline essential workers face every day.

This past spring, large retail chains like Walmart, Kroger, and Amazon introduced hazard pay under a variety of names (“Hero Pay,” “Appreciation Pay”), paying single bonuses or supplementing workers’ hourly wages by up to $2 per hour. Then, over the summer, they quietly ended the practice.

There’s a triple injustice in these developments. Prior to the pandemic, millions of workers had been denied a living wage that could sustain a family. People employed as home health aides, nursing assistants, cashiers and retail salespersons, janitors and cleaners, security guards, and laborers had been making, on average, hourly wages below $15 an hour.

According to a Brookings Institution analysis, almost half the 50 million people who work in frontline essential jobs fall into this category.

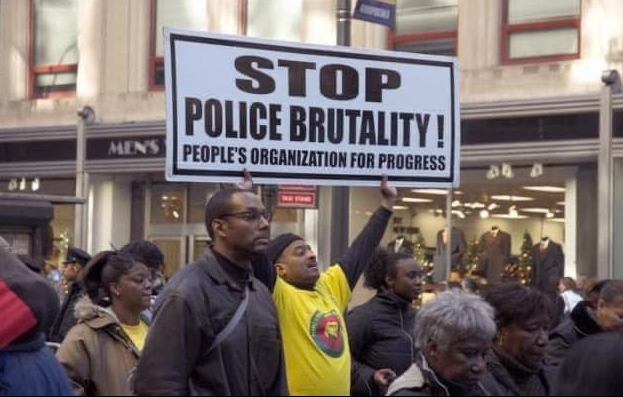

Then there’s the racial inequity in frontline, essential work. As the Brookings researchers noted, Black and Latinx workers make up a disproportionate number of low-wage, frontline, essential workers (i.e. Black workers in 2018 constituting 13 percent of all workers, but 19 percent of low-wage workers; Latinx workers making up 16 percent of the U.S. workforce, but 22 percent of frontline, low-wage essential workers).

As people struggle to get by on these inadequate wages, risking infection for themselves and their loved ones, the profits of many companies, particularly large retailers like Amazon and Walmart, have continued to soar, adding billions to the personal wealth of owners and major shareholders. And connected to this fact is the third inequity: that of exposure and risk.

Chuck Collins, author and program director at the Institute for Policy Studies, said it best: “These billionaire owners are like military generals sitting in protected bubbles sending their workers into the viral line of fire with insufficient shields.”

To be sure, hazard pay is a temporary measure that doesn’t address the long-term structural inequality that existed before Covid. But sufficient additional compensation (at least $5 an hour extra) will help millions of people make ends meet, reduce food and housing insecurity, and help workers care for other family members who have been laid off during the pandemic.

As the Brookings researchers described it, hazard pay is “a down payment on what should be permanent, lasting change through an increased minimum wage.”

Achieving this change won’t be easy. Continued pressure from the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union (UFCW), along with support from Senators Elizabeth Warren and Sherrod Brown, recently enabled thousands of grocery workers at several chains to obtain hazard pay retroactive to the summer (and, in some cases, modest bonus payments).

But the effort to secure just compensation for millions more, along with the dignity and respect that goes with it, will require substantial, continued struggle – and a much deeper public understanding of the profound inequality affecting us all.

Andrew Moss, syndicated by PeaceVoice, is an emeritus professor (English, Nonviolence Studies) at the California State Polytechnic University, Pomona.