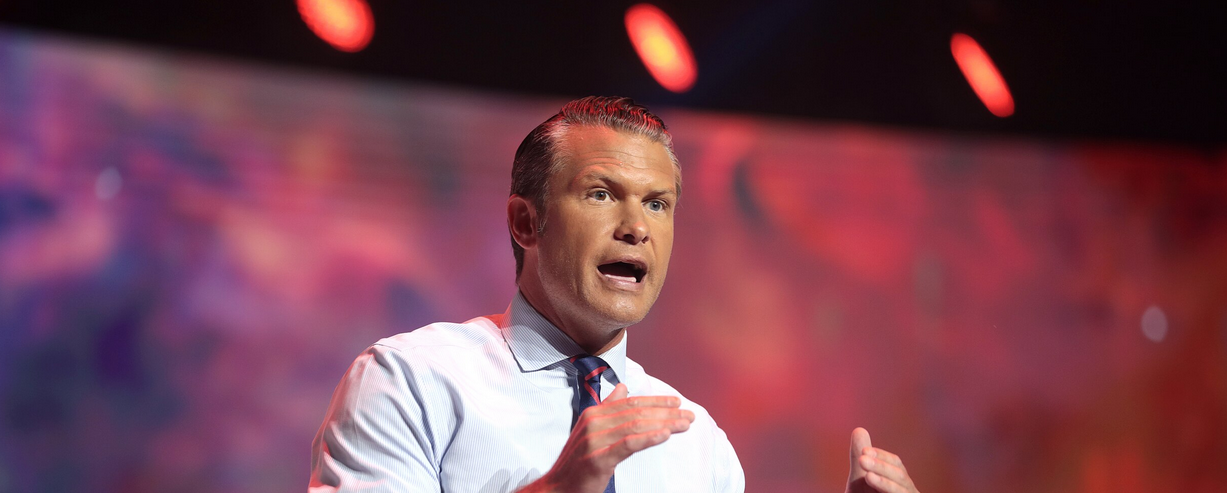

President Magufuli. Emperor complex? Photo: Facebook

Amidst growing authoritarianism and intolerance of dissent, Tanzanian President John Magufuli’s latest move takes away the ability of individuals and NGOs to file cases against the government in the African Court on Human and People’s Rights—continental court that Tanzania hosts. This is not only a grave threat to human rights in the country but also sends the wrong message to African governments and thwarts African efforts to establish continental human rights bodies.

“When domestic mechanisms fail and there is no rule of law, independent regional and international mechanisms are essential to ensure accountability and human rights for all,” said Anuradha Mittal, executive director of The Oakland Institute. “The Magufuli administration’s action to pull out from the African Court on Human and People’s Rights further entrenches the human rights crisis that has been building in the country since 2015 with passage of various legislations criminalizing dissent and freedom of opinion,” she continued.

Similarly, basic rights to life, security, food and housing, freedom from arbitrary arrest, and more—are being systematically denied to the Indigenous Maasai pastoralists in the Loliondo and Ngorongoro regions of northern Tanzania. The Oakland Institute’s research and advocacy has exposed the plight of the Maasai villagers who face intimidation, violent evictions, arrests, beatings, and starvation—by the Tanzanian government to benefit safari and game park businesses. Following violent evictions of Maasai villagers from their legally registered land in August 2017 which left 5,800 homes damaged and 20,000 homeless, four impacted Maasai villages sought recourse against the government—perpetrator of these abuses—in the regional East African Court of Justice (EACJ). In September 2018, EACJ granted an injunction prohibiting the government from evicting communities, prohibited the destruction of Maasai homesteads and confiscation of livestock on said land, and banned the office of the Inspector General of Police from harassing and intimidating the plaintiffs, pending the full determination of their case. Despite this, intimidation and threats continue which allegedly led to the expert witness for the plaintiffs not showing up at the last hearing in November 2019.

“In case of failure to secure justice at the regional court, Tanzania’s withdrawal from the African Court, takes away the ability of the Maasai villagers to seek redress at the continental court, thereby severing a vital path to peace, development, and security,” said Mittal. According to Amnesty International, Tanzania has the highest number of cases filed against it and judgments ruled against it by the African Court. By September 2019, 28 decisions out of the 70 decisions issued by the court—or 40 percent—were on Tanzania.

“With a full-blown human rights crisis in the country which threatens stability and democracy, it is essential that the Tanzanian government immediately reverses its decision. Instead of weakening African human rights bodies, it should work to strengthen its domestic judicial system. The Magufuli administration needs to understand and respect that when a government recklessly violates the rights of its citizens, international scrutiny and action is paramount,” Mittal continued.