Mohammed Khaku\Speak Up!

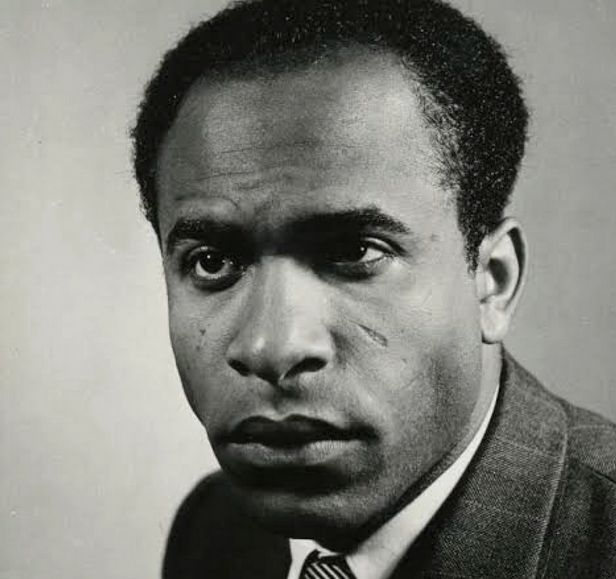

Photos: Wikimedia Commons

Africa’s future depends on bringing Fanon’s inspiring vision to life through real action that upholds justice, dignity, and self-determination. A tribute to Frantz Fanon, the fearless revolutionary Prometheus, whose powerful words left a lasting impact: Frantz Fanon (1925–1961) — doctor, revolutionary, and pioneer of decolonization.

Frantz Fanon was a French West Indian psychiatrist and political theorist from Martinique, a French colony. He’s widely known for examining the psychological impact of colonialism and for championing the decolonization of African countries.

Fanon’s influential books, like “Black Skin, White Masks” and “The Wretched of the Earth,” left a deep mark on post-colonial studies and critical theory. A committed Pan-Africanist and member of the Algerian National Liberation Front, he championed Algeria’s fight for independence from France. His bold ideas and passionate words have sparked liberation movements across the globe, from China to South America.

He was born on July 20, 1925, on the Caribbean island of Martinique, the fifth of eight children in a middle-class family descended from African slaves brought to work on sugar plantations. When his father, Casimir, a customs inspector, died in 1947, his mother, Eleanore, took charge of the household. To support the family, she opened a shop selling draperies and hardware. Of Alsatian descent, her heritage blended Celtic, Roman, Germanic, and French roots.

Frantz’s name carried echoes of the Alsatian past. Her mother’s parents disapproved of her marrying a man with darker skin. Resembling his father, Frantz became the least favored among his mother’s children, often labeled a troublemaker and kept at a distance.

At 17, he set off from home and sailed to the Caribbean island of Dominica in search of adventure. From there, he made his way to France to join the Free French Forces in their fight against Nazi Germany. Later, while stationed in French-controlled Algeria, he was awarded the Croix de Guerre, France’s version of the Purple Heart, for his bravery. Despite his service, he faced racism, noticing that white French women refused to dance with Black soldiers who had helped liberate them from Nazi rule.

While serving in the army, he delved into philosophy, exploring the works of Mauss, Heidegger, Lévi-Strauss, Marx, Hegel, Lenin, and Leon Trotsky. Later, he worked in psychiatry at a hospital in Lyon, France, where he met and married Marie Josephe, a young white French woman with Corsican and Gypsy roots. Frantz wrote a thesis called ‘The Desalination of the Black Man,’ which was rejected but eventually became the foundation for his book ‘Black Skin, White Masks.’

After training with the renowned Spanish humanist psychiatrist François Tosquelles, he earned his license. Eager to head a psychiatric ward in the French-speaking world, he applied to many institutions before finally being offered a position at the Blida-Joinville hospital in Algiers, Algeria.

Racial discrimination persisted, and in 1954, Algerians rebelled against French repression, leading the French government to retaliate with physical abuse toward its subjects.

These events were a turning point in Frantz’s political outlook, leading him to join the freedom fighter group Front de la Liberation Nationale (FLN). Growing more devoted to the cause, he resigned from his position to work full-time as a community organizer, writer, and activist for the FLN.

His commitment came at a steep personal price, as he faced death threats and even attempts on his life. In early 1957, the French colonial authorities exiled him to Tunisia, further igniting his growing passion for political activism.

During his time in Tunisia, he became popular among the locals and emerged as an advocate for African independence movements, traveling across the continent to promote the cause. His work included founding the magazine Mujahid and serving as an ambassador for the provisional government of Algeria’s liberation movement.

With its powerful writing, oratory skill, and engaging voice, the magazine quickly gained popularity. It brought together anti-colonial movements, shedding light on the struggles and experiences of Algerians under colonial rule. It sparked a sense of national identity and pride, rallying support for the Algerian War of Independence, and especially celebrated the women in hijabs leading the way.

Drawing on his experience as a soldier, he taught FLN members how to resist torture and shared valuable combat skills. Traveling from Mali to the Sahara, he visited freedom fighter camps, training both fighters and nurses in treating wounds. Between 1957 and 1959, Fanon endured a massacre by French forces and survived an assassination attempt in Libya. Later in 1959, he was severely injured during an attack at the Morocco-Algeria border.

In 1960, after wrapping up a significant intelligence mission from Mali to Algeria, he was diagnosed with leukemia. The following year, he traveled to the Soviet Union for treatment but was told the best care was in the United States. Under the alias Ibrahim Fanon, he arrived in the U.S., only to be detained by the CIA for ten days without receiving any treatment.

During this time, he came down with pneumonia, which led to his death on December 6, 1961, in Bethesda. His body was returned to Algeria, where he had gained citizenship, and he was honored with a hero’s ceremony and military recognition before being laid to rest in an FLN veterans’ cemetery.

Across the Global South, Asia, and the Middle East, the shadow of Zionist colonialism still looms large, fueled by racial capitalism, exploitation, and environmental damage that threaten entire communities. From South Africa’s townships to Sudan’s deserts, from Chiapas’ mountains to Palestine’s occupied lands, oppression takes countless subtle and brutal forms—but so does resistance. In these ongoing struggles, the ideas and actions of Frantz Fanon remain as relevant and powerful as ever.

Fanon, a psychiatrist, revolutionary, and thinker, understood that true liberation goes beyond politics—it’s also about the psychological, cultural, and economic. Winning independence without freeing the mind, reclaiming the land, and rebuilding society is like raising an empty banner over hidden chains disguised as democracy, human rights, and freedom. In works like Black Skin, White Masks and The Wretched of the Earth, he urges the colonized to confront both external and internalized oppression and reclaim their full humanity. These books deserve a spot in high school and college curricula.

His lessons still carry weight today. The Global South continues to bear the deep scars of imperialist rule—genocidal settler colonialism in Palestine, mineral exploitation in the Democratic Republic of Congo, land grabs in southern Africa, and harsh austerity measures imposed through debt in South Asia, the Caribbean, and South America. Fanon’s message is clear and powerful: freedom isn’t handed to the oppressed; it’s something they must claim for themselves. This part II looks at how his ideas still inspire anti-imperialist struggles, fueling liberation movements, revolutionary action, and modern resistance across the Global South.