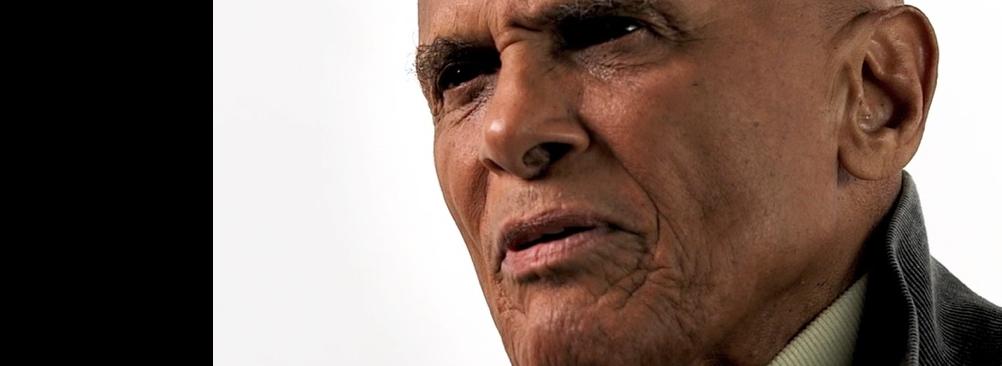

Harry Alford

[Op-Ed]

Many in Washington who follow policy debates, particularly as those discussions and subsequent legislation would affect minority-owned businesses, are familiar with Harry Alford and the organization he leads, the National Black Chamber of Commerce.

From the organization’s inception in 1993, Alford has taken decidedly pro-business and pro-minority business stances on a host of issues: from a demand to include minority-owned accounting and financial firms to monitor the $700 billion bank bailout in 2008 in what was initially a sole-source contract to two non-minority firms to recent advocacy in opposition to legislation that would have terminated all affirmative-action programs inside DOD. This short list does not begin to do justice to the breadth of Mr. Alford’s concerns.

One can have well-grounded disagreements with aspects of Alford’s positions — or even reject them whole-cloth – but it seems easy to understand why he takes the positions he does. As the head of a business chamber, Mr. Alford represents the interests of his members. He has done so publicly and unapologetically.

This, in part, is what is so troubling about a front-page profile of Mr. Alford that Washington Post published on Tuesday.

The piece chronicles Mr. Alford’s campaign against new EPA rules to restrict ground-ozone emissions, or smog. Alford contends that the rules would undermine businesses and hamper employment, especially minority employment, in the process.

In and of itself, that hardly seems worthy of a front-page profile, particularly since other business groups raised similar objections and since the article itself acknowledged that Mr. Alford was “a veteran of multiple campaigns to quash regulations….”

So what makes Mr. Alford, a self-professed conservative, worthy of such coverage? The hue of his skin? “In smog battle, industry gets help from unlikely source: black business group,” blared the headline to the article by Joby Warrick.

Presumably, what made the National Black Chamber of Commerce’s support of industry so “unlikely” was not that it is business chamber. No, it is that this business chamber happens to represent African-American members.

Warrick is a seasoned journalist and a Pulitzer Prize winner, but this piece resonates with a disappointing tone-deafness. The absurd and offensive implication here is that it is somehow odd that an African-American business group would support the interests of businesses. The Washington Post thus demonstrates a kind of twisted double standard.

The Washington Post does not, for example, question that fact that Thomas J. Donohue, the president of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, opposes the EPA rules for much the same reason that Mr. Alford opposes them. And why doesn’t it question Mr. Donohue’s position? Because Mr. Donohue is the head of a business chamber, and heads of business chambers protect the interests of their members against policies they view as hostile to business.

Readers are not well served by the glaring omission in the story’s opening paragraphs:

For years, the air over central Pittsburgh has ranked among the country’s dirtiest, with haze and soot that regularly trigger spikes in asthma attacks, especially among the urban poor. So it might have seemed odd that a black business group would choose this spot to denounce proposed restrictions on smog. But that’s exactly what the head of the National Black Chamber of Commerce did this month. Chamber President Harry C. Alford appeared before some of Pittsburgh’s African American leaders to urge opposition to a White House plan for tougher limits on air pollution.

Here is what Mr. Warrick dropped from his lead of the story: that the Pittsburgh event Mr. Alford attended and that the story apparently cites was jointly hosted by his organization and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. Inclusion of this fact would have diminished the narrative that Mr. Alford and the NBCC are nothing more than window dressing for an industry cause – as opposed to an industry partner.

The story also implicitly sets up a kind of moral standard for African-American leadership and allows a rival of Mr. Alford’s to act as jury and judge.

Ron Busby, president of the U.S. Black Chamber Inc., argues in the piece that smog contributes to health problems in African-American communities. That’s a fair enough point. But then he goes on to suggest that Mr. Alford has no standing. “Anyone who’s saying it’s not affecting our community isn’t speaking on behalf of black people,” Mr. Busby is quoted as saying.

Again, how could the author omit a crucially important fact about Mr. Busby? Not only is he a rival, he and Mr. Alford were entangled in a legal dispute. The Washington Post owed it to its readers to make clear that Mr. Busby was hardly a dispassionate analyst.

Finally, the story leaves the impression that Mr. Alford is the only significant African-American leader raising concerns about the EPA’s proposed regulations. Not true; has not been true for decades. In 1996, for example, lobbying by an American car manufacturer persuaded members of the National Black Caucus of State Legislators to withdraw a resolution calling for strengthening air quality provisions. Why? Because of the fear of job loss to African-American workers in those members’ legislative districts were those plants to close.

Today, other African-American leaders have argued that the economic consequences of the regulations would be severe in urban communities, including Mayor Karen Freeman-Wilson of Gary, Indiana. Even President Obama decided to abandon a similar proposal around the time of his reelection, apparently concerned of the damage it would do to the economy. But none of this is mentioned.

Whether one agrees with Alford’s assessment of the environmental and economic impacts of the EPA’s new rules proposal is not the issue. Readers are led to conclude that Mr. Alford stands alone on the margins in opposition to them.

Let’s set aside other critiques of the piece for the time being. The overarching point is that Mr. Alford, as the leader of a business group, has every right to join his industry partners in protesting what he views as bad policy. The hue of his skin has nothing to do with that.

Khalil Abdullah, a former executive director of the National Black Caucus of State Legislators, is also a former editor/writer for New America Media and former managing editor of the Washington Afro Newspaper.