Photos: YouTube Screenshots

Xie Xiaoliang is one of Harvard’s premier scientists, a biophysical chemist known for his work on DNA. He’s leaving Harvard to take an academic position in his home country, China, one of about 1400 top Chinese scientists who in recent years have given up their US positions and returned to China.

Xie Xiaoliang

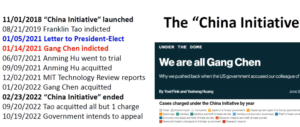

The reason is not so much China’s “Thousand Talents” program, which seeks to entice scientists to return home with promises of lucrative academic and research positions. It’s the lingering effects of the Trump and Biden justice department’s China Initiative.

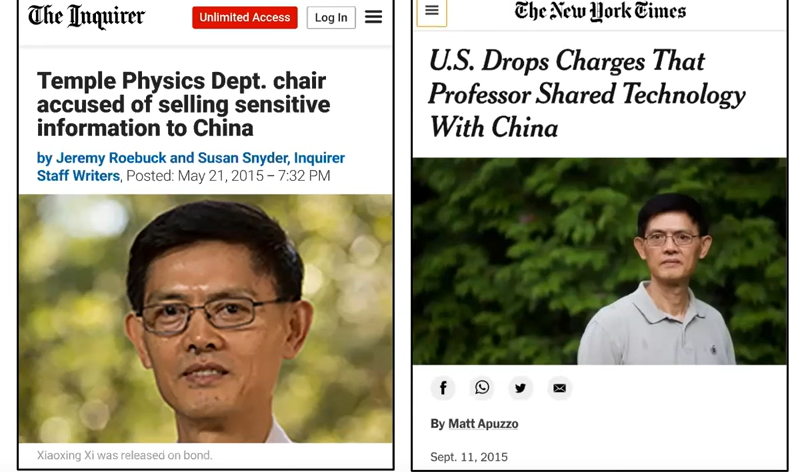

That program sought—with outstanding failure—to weed out Chinese scientists, including Chinese Americans, who were supposedly committing economic espionage. The University of Michigan’s president was among many major university leaders who wrote to the US attorney general to complain about the unfairness of the China Initiative, pointing out its racial profiling, lack of evidence of wrongdoing, and pressure on the university to “investigate researchers who are singled out only because of their personal or professional connections with China.” The open letter was signed by the overwhelming majority of Michigan faculty.

The China Initiative has ended, but the careers of a number of prominent scientists of Chinese descent in the US were ruined or set back. Fear stalks Chinese visitors and citizens alike. A 2022 survey of 1,300 scientists of Chinese descent at American universities found:

“a strong sense of uneasiness and fear: 35% of respondents feel unwelcome in the United States, and 72% do not feel safe as an academic researcher; 42% are fearful of conducting research; 65% are worried about collaborations with China; and a remarkable 86% perceive that it is harder to recruit top international students now compared to 5 years ago.”

A large majority of these scientists had experienced insults and personal animosity. Thus, 61 percent of the scientists reported considering leaving the United States for another country despite the fact that “an overwhelming majority (89%) of our respondents indicated their desire to contribute to the US leadership in science and technology.”

A Valuable Resource

That is particularly unfortunate for several reasons.

First, Chinese scientists and engineers form a significant proportion of all new Ph.D.’s from US universities: 17 percent in 2020. The great majority had intended to remain in the US prior to the China Initiative.

Second, China has become a science superpower if one judges from the scientific papers its scientists publish. Its scientists now out-publish US scientists in scientific and technological journals. Moreover, scientific papers co-authored by US and Chinese scientists outnumber any other collaborative papers by a wide margin.

“Seventy-nine percent of collaborative papers in 2018 had at least one author who was of Chinese descent working in the United States or who had previously worked or studied in America before returning to China, according to a working paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research.”

Put simply, the scientific research of Chinese scientists is crucial to international scientific collaboration (Karin Fischer, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Latitudes, June 14, 2023).

“So much of our intellectual technological power is from immigrants,” said Steven Chu, one of the signers, a Nobel Prize-winning physicist at Stanford University and a former U.S. secretary of energy. “We’re shooting ourselves not in the foot but in something close to the head.”

Roughly 300,000 Chinese graduate students and researchers are in the US. Outside the halls of Congress, where alarm bells constantly go off about the Chinese threat, scientists, research laboratory directors, and university officials recognize what a resource these visitors are. Their research, the patents they create, the collaborative work they do, and (yes) the fees they pay are major contributions to American science and the institutions that give them a home.

As the Michigan letter states, Chinese scientists are crucial to “the future of the US STEM workforce.” Moreover:

“Many of our most challenging global problems, including climate change and sustainability, and current and future pandemics, require international engagement. Without an open and inclusive environment that attracts the best talents in all areas, the United States cannot retain its world leading position in science and technology.”

National Security or Academic Freedom?

There is, to be sure, reason for caution on national security grounds. Concern about research findings here being conveyed to the Chinese military is real. U.S. universities are well aware of the problem and have developed guidelines for collaborative research with security implications. As an internal study at MIT put it:

“The challenge for MIT and other U.S. universities is how to manage these pressures [to create barriers to educational and scientific exchange] while preserving open scientific research, open intellectual exchange, and the free flow of ideas and people — all of them essential for American universities to remain at the global forefront of research, education, and innovation.”

But overwhelmingly, the view at universities and research facilities is that our society and economy would pay a high price if Chinese scientists were suddenly barred from entry. That means US “visa processes should be streamlined, backlogs cleared and talented individuals given expanded opportunities to obtain green cards,” says one writer long involved in promoting US-China ties.

Congress isn’t listening, however; right-wing members, with some support from liberals, believe any contact with Chinese scientists is a national security danger. Recently, 10 Republicans on Rep. Mike Gallagher’s special committee on China wrote Secretary of State Antony Blinken to urge that the U.S. scrap the 1979 US-China Science and Technology Agreement, which is up for renewal. That agreement supports cooperation on many scientific projects in agriculture, physics, and the atmosphere, among other areas.

The committee argues, with precious little evidence, that such projects will eventually benefit China’s military. I don’t imagine Blinken will fold on this issue, but the right-wing protests and exaggerations show what engaging China is up against.

Let’s remember that no one appreciates academic freedom more than visitors from China and other countries under authoritarian rule. When that freedom is violated by harassment and suspicion, word gets back to China very quickly, and the rewards for returning to China, in money and prestige, become tantalizing.

Academic freedom is under assault in the U.S. for other reasons these days. It is in our self-interest to protect it from those who really don’t have the national interest at heart.

Mel Gurtov, syndicated by PeaceVoice, is Professor Emeritus of Political Science at Portland State University and blogs at In the Human Interest.

Comments are closed.