By Milton Allimadi

Photos: Milton Allimadi

It was around 1971 or 1972, when I was either 10, or 11 years old, when Okello p’Marino taught me how babies were made.

We lived in Bungatira village which is about 10 miles from Gulu City, in Uganda.

The Marinos were related to us and lived in an adjoining homestead.

I must say I was very disappointed with my parents that day. To think they too got naked and did such a nasty thing as described by Okello.

At the time, for some reason, I thought only perverts did such things. Of course I didn’t know the word pervert yet. But I knew what Okello described was gross.

I’d never heard about the birds and the bees. So, I just couldn’t believe my parents had sex. I thought a boy grew up, met a girl who also grew up, they fell in love, and they got married. Then, eventually, the woman’s belly grew, and grew, and grew, and one day they ended up with a kid. Then they would have some more kids. I never even thought that the kid had to emerge from somewhere. That never crossed my mind, until Okello sat me down.

One thing you need to know about Okello is that no one could laugh like him. In all the decades I’ve been alive since I’ve never encountered anyone who laughed like Okello, or enjoyed laughing more than Okello.

When Okello laughed, all the homesteads could hear. Often, he’d laugh so hard that he’d have to sit down, and even lay down on his back. Okello would laugh until he cried. Just remembering him, and the fun I had as a child growing up around Okello, and the lessons I learned, brings tears to my eyes today. So many decades later.

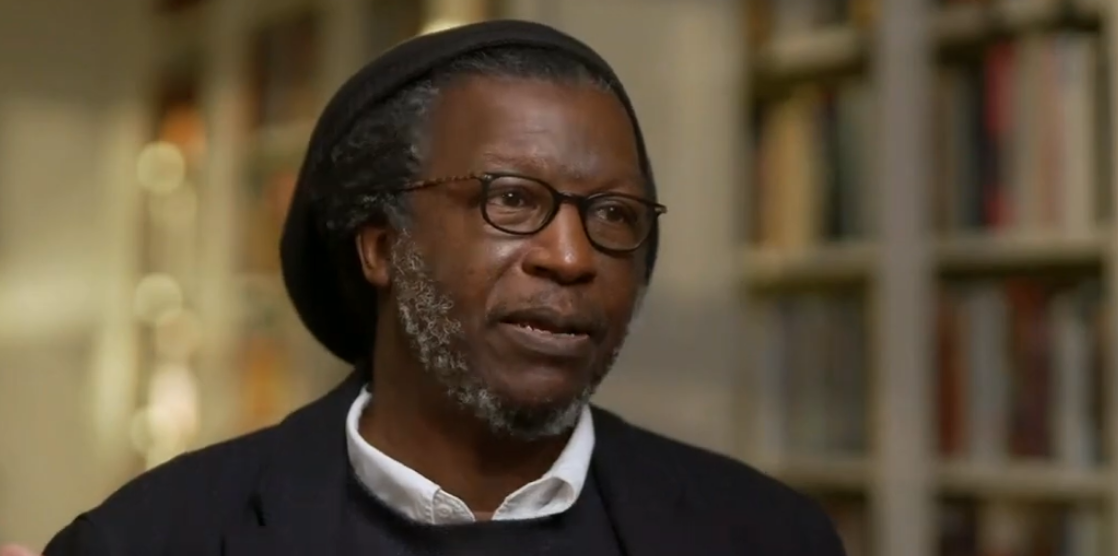

I live in the United States now. The other day, I celebrated another birthday.

Me in a recent photo.

I’ve been reflecting on the past.

I owe much of my childhood knowledge of Ugandan Luo culture—my culture—and traditions to the Marinos, especially Okello, who was just a few years older than me, and Oloya, my mother’s youngest brother.

Okello was the best marksman in all of Bungatira, when it came to felling birds with a hand-held catapult called abutida.

Okello could go hunting early in the morning and come back with his cow-hide leather bag, slung over his shoulder, bursting with as many as 40 or 50 akuri birds. I was always invited to the roasted-bird feast that lasted for days. Delicious.

I accompanied Okello on many hunts. I’m not ashamed to admit I never struck and killed a single bird with my abutida. I tried my best. Okello, on the other hand, felled birds at impossible distances. His accuracy was uncanny. I witnessed with my very own eyes Okello take down two birds with one shot from his catapult.

How could he not be a God?

I never gave up. One day, I saw an akuri bird perched on a mango tree on our compound.

Okay, this wasn’t the same as the real huge akuri that Okello hunted in the forests. But a bird is a bird.

I snuck up, stealthily, like a cat. I imagined I was the great Okello. When I felt I couldn’t get any closer without alerting the bird, I knelt, I pulled back the projectile—the hard clay marbles were called lalung—I closed one eye, I aimed, and I fired.

Lo and behold, I struck the bird! It fell right on the middle of the compound. I threw the catapult and screamed in elation. I ran to the Marino’s homestead and fetched Okello. This was my first kill.

When Okello and I got closer, the bird started moving. It flapped it’s wings. I struggled to load ammunition on my catapult.

The bird wasn’t having it. It had only been stunned. It flew away.

Oh, the humiliation! Predictably, Okello was soon rolling on his back, tears streaming down his face. Many others laughed with him.

One day, we were near the thick bamboo trees by our house in Bungatira when we spotted a snake. Before Okello could unleash one of his deadly lalung from his abutida, the snake disappeared.

Meanwhile, I’d picked up a beautiful colorful item earlier and inserted it in my pocket. Now was a good time to show off to Okello. I was always looking for an opportunity to impress Okello since he enjoyed all the glory.

“Look what I found,” I said, showing Okello the beautiful glowing object, now in the palm of my hands.

“Miny!” Okello cried out, meaning “Fool!” He struck it out of my hand.

I quickly dove to the ground, grabbed it, and thrust it back in my pocket.

Okello gasped.

“In lapoya?” he asked, meaning “Are you a mad man?”

“Meno kwidi,” he added, meaning “That’s a worm.”

I laughed at Okello. Did he take me for a fool? What jealousy. He wanted to deceive me so he could snatch the colorful object for himself. Finally, I had something that Okello didn’t have.

Okello called other Bungatira folks over. He asked me to show them my precious find.

I don’t remember who, but it was some other adult that knocked the colorful object from my hand.

“Lutino Amerika luminy ba!” this adult declared, meaning “These American children are total fools!”

It turns out that I’d pocketed a cocoon containing larva.

Yes, Okello rolled on the ground.

Okello made me fetch a piece of paper and pencil. He drew and explained the different stages of worms: egg, larvae, juvenile, and adult.

He asked me if I knew how babies were made. How I had been made.

I came from my mom’s belly, I said.

Yes, but how did I get there.

What did he mean? I had always been there. Tiny. Then kept growing.

Okay, and how did I get out of her stomach?

I confessed my ignorance.

Okello drew a picture of a man and a woman.

Then he drew a picture of the man’s genital and the woman’s. Then he explained how the man’s part went into the woman’. And how some fluid came out of the man’s and entered the woman’s. How the fluid attached to an egg. How it then grew, and grew, and grew. Then after nine months, how the baby came out of the woman’s part. Okello told me that’s how I had been born. That’s how he had been born. That’s how all humans were born.

“Mpumbavu!” I screamed at Okello, meaning “Idiot!.” I had heard my father use that word once in the past.

I tore up the paper. I was almost in tears. I was furious. How could someone who pretended to be my friend make up such a nasty story and claim my parents also partook of such activities?

I stormed off.

Then I started thinking. What if Okello was right? I remember that evening scrutinizing my mother and father carefully to see if I could detect any signs of deviancy. Of course I didn’t know that word then, but you get the picture.

How could such decent people, my parents, always telling us to be polite and proper, engage in such activities? I decided not to believe it.

President Kennedy invited Prime minister Obote to the White House in October 1962 soon after Uganda’s independence. Photo: JF Kennedy Library.

To understand why the person who finally freed the cocoon from my grasp referred to me as an American “fool,” meaning I knew nothing about nature, I must tell you why and how my family first came to the United States.

Uganda was a British colony from 1894 to 1962. I think they called it “protectorate” to make it sound less imperialistic.

The first prime minister after independence was Milton Obote. I was born the year of independence and that’s how I got the first name Milton.

If I had been born in Ghana and my father had also been a nationalist there, I might have been named Kwame or Nkrumah; in Kenya, I might have been named Jomo or Kenyatta; and, in Tanzania, I might have been named Julius or Nyerere.

My father, Otema Allimadi, was one of the young nationalists that agitated for Uganda’s independence during the 1950s. He was born in 1929, which means that he was in his twenties when he was involved in the freedom struggle. Later, when I was grown, I learned that the colonial police were always searching for him. Sometimes he was arrested. Sometimes he’d go underground.

My parents, Alice and Otema Allimadi, in the Washington, DC days.

The British, like all the European colonial powers didn’t want Africans to gain higher education on account that they’d be better prepared to agitate for Uhuru, which is the Kiswahili word for independence. So it was countries like the Soviet Union and other East bloc countries—those affiliated with the Soviet Union—that provided scholarships. My father worked clandestinely to secure these scholarships and to “smuggle” the young students out of Uganda through Sudan, to Egypt, from where they flew to Moscow.

This was all before Uganda won its independence. My father and his colleagues knew that soon, Africans would be running the country. Uganda needed educated manpower.

After all, they had witnessed the disintegration of neighboring Congo soon after its independence in 1960. The imperialists, led by Belgium and the United States, were determined to continue their hold over the Congo. The Belgians never planned to let go of this mineral-rich African country so they had made sure to prevent the emergence of an educated class of Congolese. Obviously, these are things I didn’t know when I was a child.

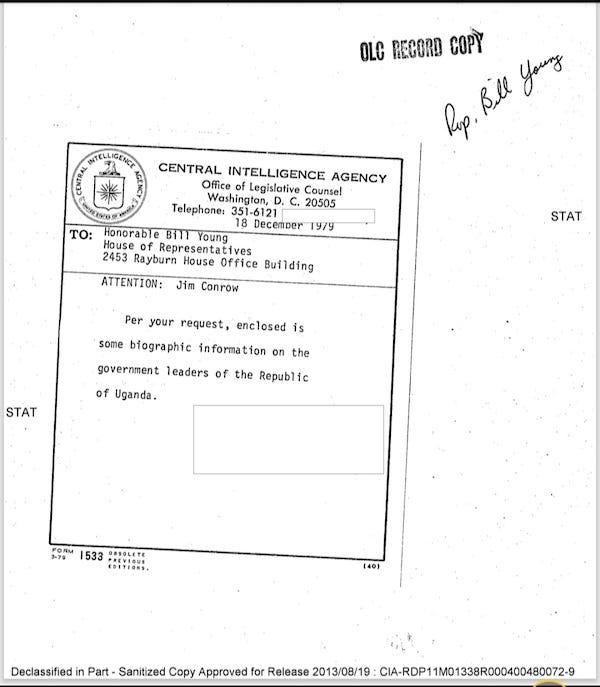

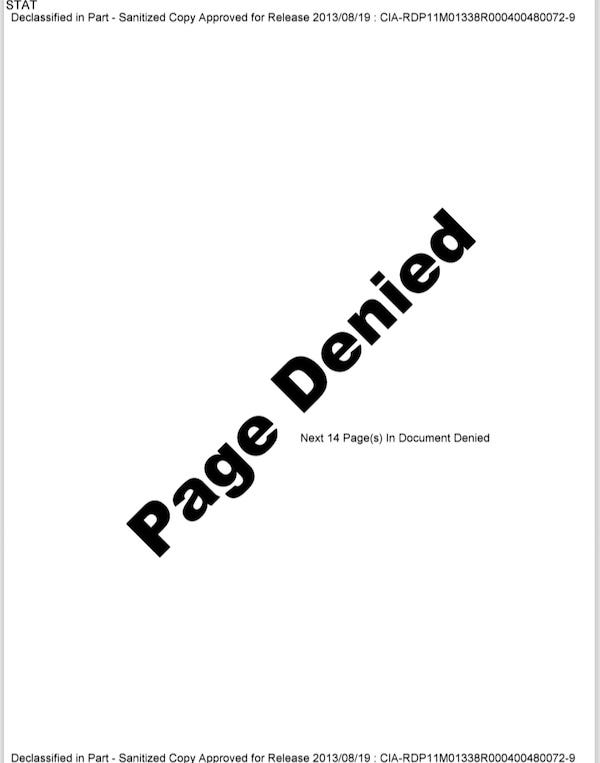

My father was appointed Uganda’s ambassador to the United States in 1966. He later became, concurrently, Uganda’s ambassador to the United Nations, and Canada—or High Commissioner as they call it. Recently, when I was doing some research, I stumbled on CIA files containing information about my father. Then I researched the names of other leaders and it became clear that the CIA must have files on all African—and other foreign—diplomats accredited, or ever accredited to the U.S., and other leaders too. One page in the file states, “Page Denied” and explains that the next 14 pages were denied; presumably they remain classified.

Hmm. Wonder what the CIA won’t let us see.

Ambassador Allimadi’s CIA file. All publicly available information. I wonder what the CIA is hiding in the 14 unreleased pages. Additional searching shows the CIA kept tabs on pretty much every foreign diplomat.

The unclassified information was a United Nations press release from September 20, 1967, about my father presenting his credentials to UN Secretary General U Thant. Additional information in the CIA file was from much later, in 1979, when my father was part of the Uganda National Liberation Front (UNLF), Ugandan exiles, who formed the government after Tanzania’s army retaliated and overthrew Idi Amin after he’d invaded Tanzania. So the CIA had kept an eye on ambassador Allimadi for a long time. The agency must have a file on every diplomat accredited to the US or UN and African leaders too.

One of several files on Nkrumah contained newspaper clippings after his death. Another mentions Nkrumah’s own claim that the CIA was involved in his ouster; later, Nkrumah was proven to have been correct. One file about Sekou Toure assessed what the CIA called his shift away from self-isolation.

**********

Decades later, I still remember the address of the Ugandan embassy where we lived when we arrived in Washington, DC: 5911 16th Street NW.

The embassy is still housed in the same building.

I was four years old at the time.

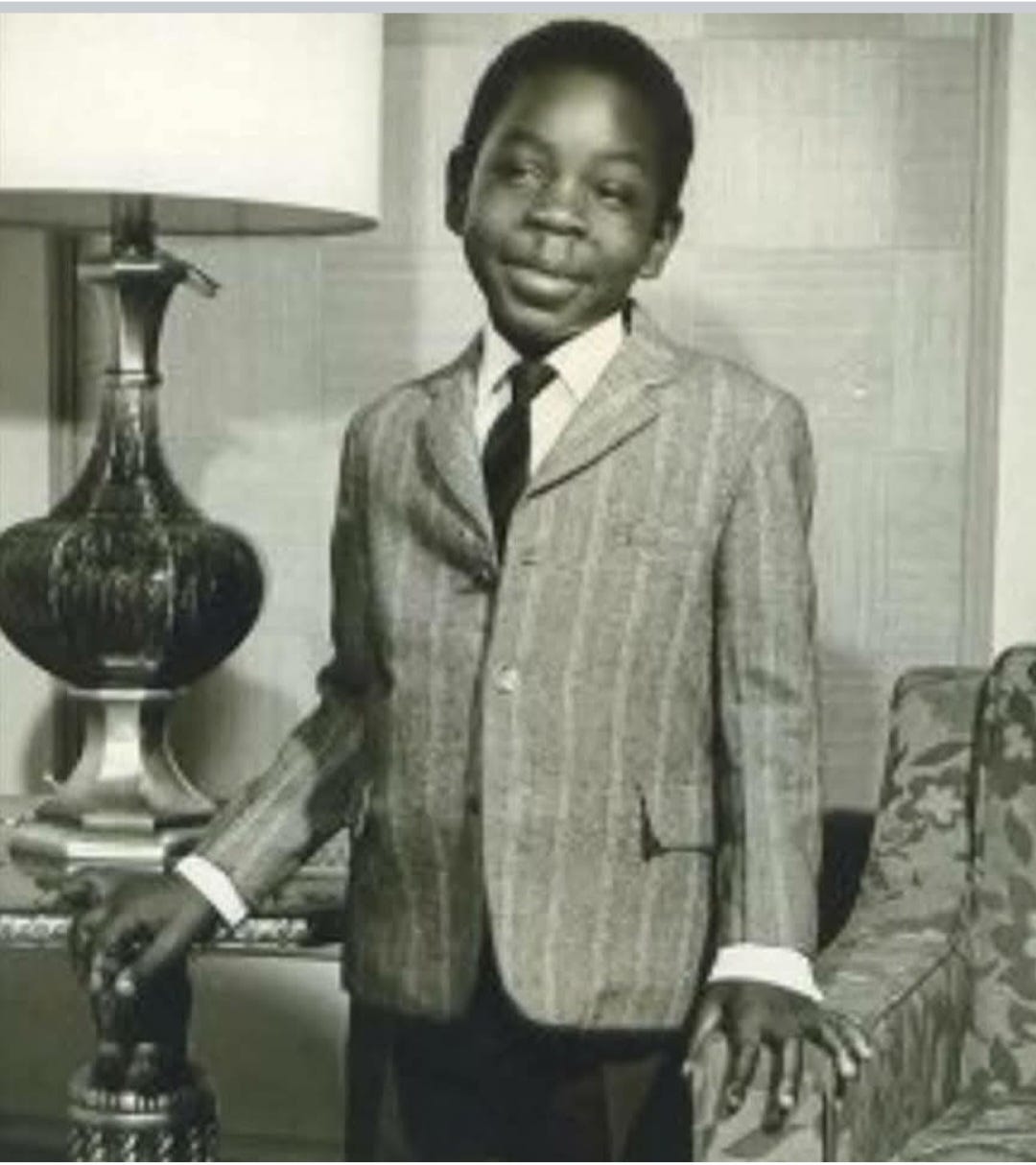

Me in the Washington, DC days, back in the day.

I remember a few incidents from back in the day. On the day of our arrival, I held a small piece of luggage and climbed up the stairs after my mother, Alice Lamunu Allimadi. In those days the embassy doubled as both residence and the office, which was in an adjoining part of the building, until we moved to a new residence years later.

I saw another kid, on my right side, also climbing up a parallel flight of stairs. He seemed very familiar. We immediately hit it off. We both placed our luggage on the steps and walked back down to greet each other. New friends.

Strangely, we wore similar clothes. I liked this kid. I could tell that he liked me too. I didn’t speak English at the time so I greeted him in Luo.

“Kop Ango?” meaning “How are you?”

To my surprise, the kid also greeted me in Luo.

I reached out to shake hands. It felt like I’d just touched a solid wall.

We were separated by a glass wall. I walked down the hallway so I could round the corner and meet him on the other side. He also walked in the same direction. When I rounded the corner, I was shocked to find no one there.

I came back to the other side. There he was. He was seized by a look of alarm and panic. I also remember yelling and running up the stairs calling my mother’s name.

Later, I learned that I had met myself, face-to-face, for the first time.

I remember an incident from my school in D.C., either in the first or second grade. I don’t remember the name of the school.

One day, the teacher said she smelled something awful. She made us all come to the front of the class and line up. She walked behind us and she inspected our underpants for evidence of poop. She did not find any. Now, when I look back, I wonder about this teacher. What else…?

One day, this same teacher called me in front of the class. I stood next to her facing my peers.

She announced to the class that my father—the same ambassador Otema Allimadi—was a big chief in Africa. She told my classmates that as the chief’s son, I got to play with elephants and lions.

I didn’t recall such things. I remember glancing up at the teacher.

“Isn’t that right Milton?” she said, while squeezing my shoulder. Too firmly.

“Yes,” I said, nodding in agreement.

I recall the gasps and looks of admiration from the other kids. I became very popular in my class.

The other kids would come to me each day after I was dropped off at school by the driver in the black embassy Mercedes, to find out more about my adventures. The teacher had put me in a tight spot and now I had to regale my peers with tales about my adventures in the jungles of Africa.

I never told my parents or siblings about this incident. Hard for a four or five year old to figure out these things. Today, I understand how attitude toward Africa, and perceptions of the continent are formulated in this country at an early age.

**********

I want to move this story up to 1971. I was now nine years old and obviously no longer afraid of giant mirrors.

By that time, my family was living in New York City. I think I attended Horace Mann school.

We lived in the Kips Bay neighborhood in Manhattan before moving to a townhouse on the Upper East side.

I know that for some reason I didn’t like spinach even though it made Popeye The Sailor man powerful, and let him beat up Bluto who kept trying to kidnap Olive Oyl, his lady. My younger brothers, Andrew who was seven, and Walter, who was five, also didn’t like spinach.

Walter was born in the United States. Sue, after Walter, was three; Doris, an infant of two, had also been born in the US.

We had long heavy curtains that stretched down from the ceiling to the dining room floor. We found a solution for the spinach.

Whenever the grownups weren’t around we dumped our spinach behind the curtains.

“Oh, you kids are wonderful,” auntie Tina—the Jamaican lady who helped care for us—sang our praises in her lyrical accent whenever she walked in and found our plates emptied of spinach.

Odell—we also called him “Uncle Odell”—was Ugandan and also helped care for us. In those days we thought he was old, but Odell may have only been in his late teenage years.

I remember Odell was always talking about the upcoming “big fight” between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier. He spoke about it so much that I developed a great interest in boxing.

One time, I noticed that whenever I came near my mother and auntie Tina, and other grownups, they would stop talking in somber tones about whatever they’d been discussing. I knew they’d change the subject just by their demeanor and suddenly jovial tone of the conversation.

Young people can tell when something is going on. One day, I finally asked Odell what this was all about. He made sure my mother and other grownups weren’t around, then he sat me down.

Odell didn’t speak much English and he broke the news in Luo.

“Lumony pa Amin gi uturo gamente pa Obote,” he said, which literally meant “Amin’s soldiers have broken Obote’s government.”

I knew who Obote was. There was a newsreel at the embassy in DC that I used to play on the home projector. I’d watch him come down the steps off a plane. Then as soon as his feet touched the grown, I’d play the reel backward, in fast-motion, and watch Obote walk backward in lighting speed back into the plane. I must have played that reel hundreds of times.

Gen. Idi Amin gave himself the title “Conqueror of the British Empire.” Photo Wikimedia Commons.

I didn’t know Amin. Odell explained that he was the army commander and Obote was his boss.

I asked him what “gamente,” was—it’s the Luo version of “government”—and why Amin had broken it. Why couldn’t it be fixed?

Odell was not a great civics teacher. He said everyone was gamente. He was gamente. I was gamente. My parents were gamente. Even baby Doris was gamente.

Someone else eventually explained to me what happened even though the grownups didn’t think I should know. Maybe auntie Tina.

I learned that the army had taken over power in Uganda. Even I understood the man whom I’d made walk backward countless times could no longer go back to Uganda. I also learned that it meant our father would no longer be ambassador. Later, I learned he’d planned to resign anyway. Uganda was supposed to have elections that year and he’d intended to run for Parliament.

I remember when I was in bed that night I prayed that Superman would fly into Uganda and smash up Amin’s tanks and send him and his soldiers running in every direction.

That’s the kind of clueless American I had become. Living in a fictitious universe, a habit all too common in this country. Even more so today with the infinite digital spaces.

Alas there was to be no Superman to the rescue. Soon, my family left the United States and returned to Uganda.

My father tried to retire from politics to live a quiet life as a farmer.

That was not to be. Idi Amin tried to kill him.

More on that later.

Allimadi publishes www.blackstarnews.com and is a PhD student in history at Howard University. Please feel free to support his writing via his Patreon Page.

Thanks for reading Milton’s Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.