By Wim Laven\PeaceVoice

Photos: Facebook\Video\YouTube Screenshots

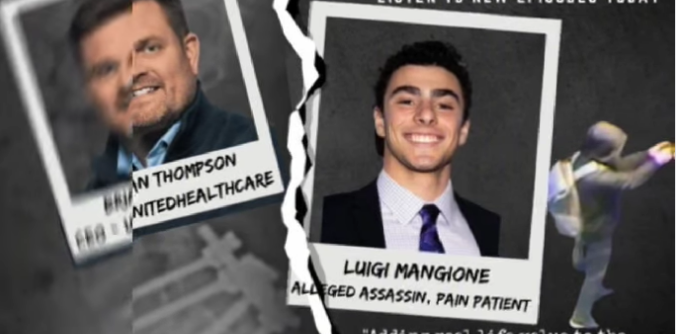

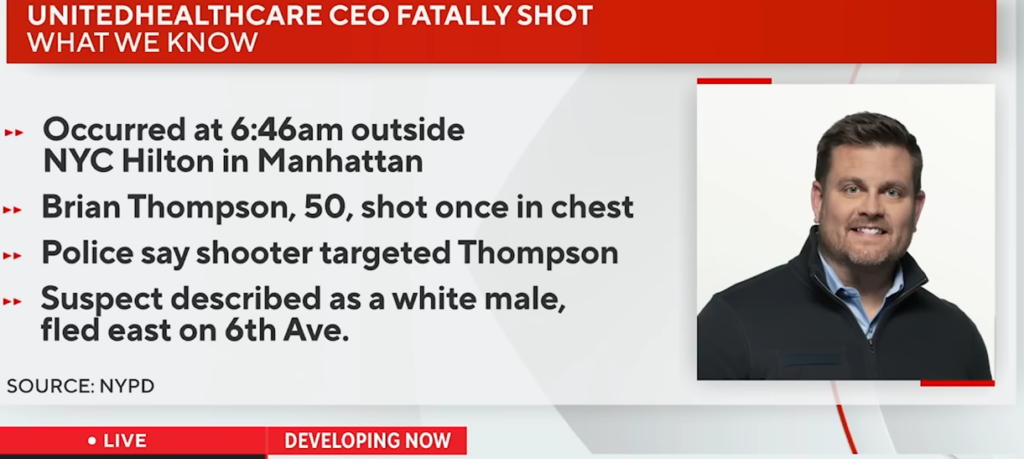

Following the murder of United Healthcare’s CEO, social media has been flooded with outrage, mostly directed against insurance companies that deny care.

On social media, I have seen reports from people I know. They express, as I do, that murder is not the answer, but they go into detail about the pain caused by the denial of their insurance claims, often due to insurance use of AI to evaluate the “need.”

Our capacity for empathy is what makes us human. I see this in my friends as they grapple with the ethical crisis: “It was wrong to shoot him, but…” One friend says it has shed light on a real problem; another says, “They don’t need him for their investors’ meeting—nothing changes.”

I surprise my friends; they know I have complained about healthcare insurance for more than a decade. They know I question whether or not a better system could have saved my brother’s life when he died at 33, but this time I give a different response.

In an early episode of the Twilight Zone (Button, Button) there is a kind of thought experiment: would an ordinary person be willing to kill a total stranger for a large sum of money? To accomplish the task all one need to do is push the button, someone they don’t know will die, and they will receive payment.

Now, my friends accuse me of being too abstract. “What does healthcare have to do with The Twilight Zone?” they ask. But isn’t that exactly what AI represents?

AI is just the substitute for the Twilight Zone button. The AI is a program that denies claims and prevents people from receiving life affirming care. The casings of the bullets that killed the CEO bore the words “deny,” “defend,” “depose.” Of course that is murder, but is it any less violent when a person dies due to lack of access or treatment? The people making profits clearly are disconnected from the people that die when their insurance doesn’t cover needed treatment or testing.

In classrooms I talk about violence regularly. Most of the time people think of direct violence like physical assaults, murder, or war when the subject comes up. But there are also forms of indirect violence that can be cultural, structural or systemic. One of the most common I discuss is about access.

Paul Farmer, a medical doctor dedicated to providing medical services to those who cannot afford care, provides a fantastic description dealing with medical treatment:

“The term ‘structural violence’ is one way of describing social arrangements that put individuals and populations in harm’s way […] The arrangements are structural because they are embedded in the political and economic organization of our social world; they are violent because they cause injury to people (typically, not those responsible for perpetuating such inequalities). With few exceptions, clinicians are not trained to understand such social forces, nor are we trained to alter them. Yet it has long been clear that many medical and public health interventions will fail if we are unable to understand the social determinants of disease.”

The definition comes in response to the observation:

“Because of contact with patients, physicians readily appreciate that large-scale social forces—racism, gender inequality, poverty, political violence and war, and sometimes the very policies that address them—often determine who falls ill and who has access to care. For practitioners of public health, the social determinants of disease are even harder to disregard.”

I do have concern for medical personnel. They are working hard yet are receiving lots of the person-to-person blame for disappointing outcomes in treatment. Going through the testimonies of people who have watched loved ones anguishing in pain or dying makes the rage understandable.

Insurance companies have apparently outsourced life and death medical decisions to AI, and they may even blame it on a fiduciary responsibility to maximize profit for shareholders. Insurance companies dictate so much of our treatment pathways that it’s easy to forget their primary existence is not to improve patients’ quality of life but to generate profit.

Doctors take an oath: ‘First, do no harm.’ Insurance companies, however, have no such obligation. Increasingly, the public is paying the price, and I really hope that we can change the narrative from revenge and bloodlust in perceived reaction to what these companies are doing to one of change that starts producing quality healthcare from everyone. With people power we can make this needed change.

Wim Laven, Ph.D., syndicated by PeaceVoice, teaches courses in political science and conflict resolution.