Photo: YouTube

The Democratic National Committee’s decision to replace Iowa with South Carolina to the front of the presidential primary line – displacing both Iowa and New Hampshire – has created a stir over race and entitlement. Despite the hoopla, the practical benefit for the state Democratic Party is a purely symbolic one – that’s because if Biden runs, as expected, he is unlikely to face a challenger.

Nonetheless, for Black political culture, the selection is like listening to a soulful tune by the South Carolina native James Brown – it triggers the emotional memory of a people’s journey through separation, pain, hope, and pride. Understand that the state holds a special place in our political history – where race has been key to wielding power since the days of slavery.

The party validation of Black voter concerns is an extension of the march to freedom codified in the 1964 Civil Rights Act and 1965 Voting Rights Act. For the Democratic Party, the elevation of diverse voices in the primary helps to transform an institution defined by white supremacy – and nowhere more than in South Carolina.

“Please, Please, Please”

While slavery in Virginia evolved gradually to replace indentured white servants, the South Carolina colony was intended as a slave society from the beginning. In 1670, Africans were forced to Charleston by British slave traders and planters from Barbados seeking cheap land. They used Africans to clear the swamps, build the town, and grow rice as in west Africa.

Africans comprised a majority of the population of colonial South Carolina and planters relied on brutal methods to control enslaved workers. They lived in encampments with concentrations that enabled the preservation of elements of African language, spiritual, and cultural practices. They were the ancestors of the “Gullah Geechee people” of coastal South Carolina and Georgia.

Over two centuries, Africans fled the rice plantations for freedom in isolated swamps and islands. The settlements were known as maroon colonies and ranged from small groups to towns with defensible walls, as historian Timothy James Lockley detailed in “Maroon Communities in South Carolina.”

During the Civil War, the Blacks of coastal South Carolina and Georgia were awarded ownership of the abandoned lands. In 1865, Union Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman issued Field Order No. 15 to grant ex-slaves with plots in reparation for servitude.

It was a controversial decision that did not survive the murder of President Lincoln, but may justify Blacks staking a claim in the states today.

By 1865, the experiment in self-governance was cut short as land awarded in reparation was deemed illegal and restored to seditious planters; families that had established farms on the plots were evicted. The South Carolina Democratic Party arose as an instrument of white supremacy in opposition to the victorious Republican Party – and what it saw as “Negro rule.”

South Carolina led the way in the enactment of race laws known as “Black Codes” meant to restore conditions of slavery. By 1867, the federal army intervened to give Blacks a chance at freedom. Yet, by 1876, South Carolina was once again under the control of the Democratic Party and Gov. Wade Hampton, a former commander of Confederate forces. Black citizenship was crushed under layers of Jim Crow laws and violence.

One of the most notorious state leaders was Ben “Pitchfork” Tillman (1847-1918), who served as governor and senator, and a voice of repression. In 1900, he defended white supremacy on the floor of the U.S. Senate, saying, “We of the South have never recognized the right of the negro to govern the white man, and he never will. We have never believed him to be equal to the white man.”

By the 1940s, the South Carolina Democratic Party was led by Strom Thurmond (1902-2003), who served as governor and U.S. Senator for a record 46 years. He was governor when President Harry Truman signed an executive order in 1948 ending segregation in the military. Thurmond lashed out in a speech, saying, “I want to tell you, ladies and gentlemen, that there’s not enough troops in the army to force the Southern people to break down segregation and admit the Negro race.”

That year, he campaigned for president as a protest candidate against Truman. He ran under the States Rights Democratic Party – or “Dixiecrats” – an alliance of southern Democrats disaffected with the national party’s stance on civil rights. He won South Carolina, Mississippi, Alabama and Louisiana in the general election, and the states’ 39 electoral votes.

Until that point, national party leaders had managed to hold together a sectional coalition by turning a blind eye to Jim Crow as a local issue. The party rewarded southern allies with vast federal investments like military bases and infrastructure projects.

“Papa Don’t Take No Mess”

The civil rights movement made it impossible for the nation – and the Democratic Party – to continue to ignore racial injustice in the South.

The sit-ins, demonstrations, and petitions brought about a heightened awareness in South Carolina and especially in Orangeburg, a majority Black city and home to two colleges.

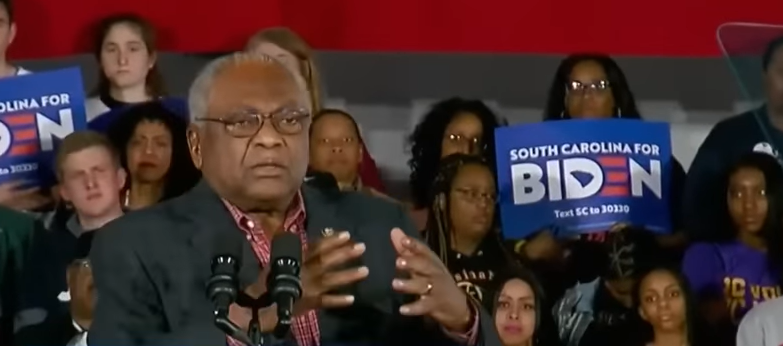

During the 1960s, students began to challenge the city’s Jim Crow restrictions. Among them was the current South Carolina Democratic leader, Rep. James Clyburn, elected in 1993 as the first Black congressman from the state since the Reconstruction era. He met his late wife Emily England Clyburn, a descendant of the Gullah Geechee community, in the Orangeburg jail in 1960 during a civil rights demonstration.

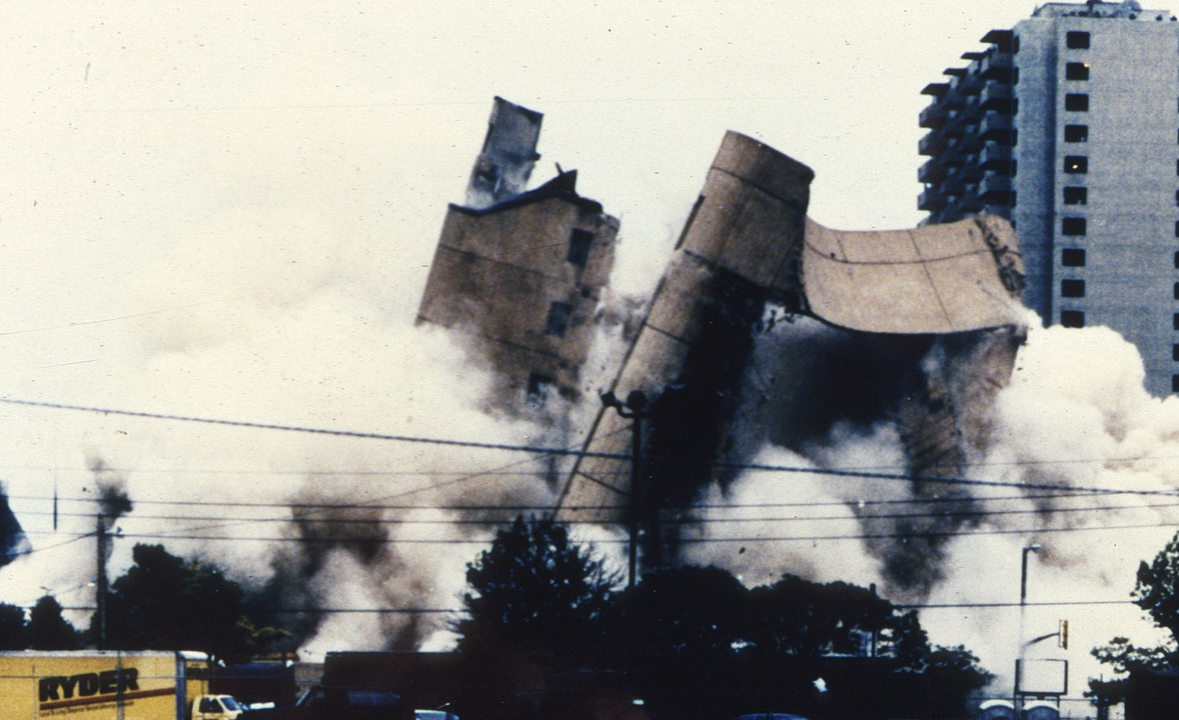

In February 1968, students rose up in opposition to a segregated bowling alley that denied entry to a Vietnam War veteran. About 300 from South Carolina State College and Claflin University engaged in peaceful protest. As local police attempted to stop the demonstration, however, a melee ensued. Democratic Gov. Robert McNair ordered state police and the National Guard to restore order. As 200 students returned to the campus of S.C. State, a fire truck with armed escort followed them and shotgun fire wounded 28 and killed three – almost all were shot in the back in an incident known as the Orangeburg Massacre.

The civil rights movement forced the national Democratic Party to shift from coddling the southern wing to championing racial justice. It did so with the understanding that racial equity would rupture its alliance with the white South, but bet that it could offset the losses with enfranchised Black voters. With enactment of the 1965 Voting Right Act, Blacks in the South flocked to the Democratic Party.

In response, southern white Democrats stampeded to the Republican Party, which embraced the states’ rights agenda of disaffected segregationists. South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond joined the Republican Party and helped to forge a realignment known as the “Southern Strategy.” By the 1980s, the political parties in the South served as yet another signifier of race.

In recent years, Blacks have been the foundation of the Democratic Party in the South – but their political influence is limited to the predominantly Black cities, towns and congressional districts. White Republicans, by contrast, hold power over city, county, state, and federal elected offices and government agencies.

Today, the long-standing barrier to Black statewide influence has begun to ease. The progress is due to demographic shifts, economic expansion, federal election laws, and Black Democratic organization. The transformational inclusive states are Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, and Georgia.

Not so in South Carolina, where Blacks comprise 30 percent of the population, but remain largely shut out of state power. Still, the effort of state Democrats to forge inclusive coalitions has moved the state Republican establishment to expand its footprint. In 2011, Nikki Haley took office as governor with the backing of the Tea Party; in 2013, she appointed Tim Scott to a vacant seat in the U.S. Senate and he was re-elected to two full terms.

Despite the notable exceptions, the reality is that major state offices and legislative seats remain in the hands of conservative white men, as always.

In closing, the Democratic Party selection of South Carolina to lead-off its presidential primary is a symbolic gesture – but one with real significance in the political saga. To be the first voice heard in the primary process is a tribute to the Black community’s long struggle for justice.

Roger House is associate professor of American studies at Emerson College, Boston, and author of “Blue Smoke: The Recorded Journey of Big Bill Broonzy.” The article is reprinted from The Daily Beast.