Photos: YouTube Screenshots

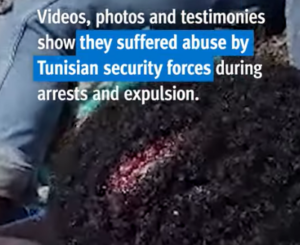

(Tunis) – The Tunisian police, military, and national guard including the coast guard have committed serious abuses against Black African migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers, Human Rights Watch said today. Documented abuses include beatings, use of excessive force, some cases of torture, arbitrary arrests and detention, collective expulsions, dangerous actions at sea, forced evictions, and theft of money and belongings.

Yet on July 16, the European Union (EU) announced the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with Tunisia on a new “strategic partnership” and a funding package of up to €1 billion for the country, including €105 million for “border management, … search and rescue, anti-smuggling and return.” Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte highlighted that the partnership would include focus on “bolstering efforts to stop irregular migration.” The MoU, which must be approved formally by EU member states, failed to include serious guarantees that Tunisian authorities would prevent violations of the rights of migrants and asylum seekers, and that EU financial or material support would not reach entities responsible for human rights violations.

“Tunisian authorities have abused Black African foreigners, fueled racist and xenophobic attitudes, and forcibly returned people fleeing by boat who risk serious harm in Tunisia,” said Lauren Seibert, refugee and migrant rights researcher at Human Rights Watch. “By funding security forces who commit abuses during migration control, the EU shares responsibility for the suffering of migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers in Tunisia.”

The EU has already dedicated at least €93-178 million in migration-related funding to Tunisia cumulatively between 2015 and 2022, including by reinforcing and equipping security forces to prevent irregular migration and stop boats heading for Europe. The EU should suspend funding to Tunisian security forces for migration control and set clear human rights benchmarks for any further support, Human Rights Watch said. EU member states should withhold their support for migration and border management under the recently signed MoU with Tunisia until a thorough human rights impact assessment is carried out.

In addition to the documented security force abuses, Tunisian authorities have failed to ensure adequate protection, justice, or support for many victims of forced evictions and racist attacks, at times even blocking such efforts. As a result, with respect to Black Africans, Tunisia is neither a safe place for disembarkation of third country nationals intercepted or rescued at sea, nor a “safe third country” for transfers of asylum seekers.

Since March, Human Rights Watch has conducted phone and in-person interviews with 24 people – 22 men, 1 woman, and 1 girl – who lived in Tunisia, including 19 migrants, 4 asylum seekers, and 1 refugee, from Senegal, Mali, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Cameroon, and Sudan. Nineteen had entered Tunisia between 2017 and 2022, twelve irregularly and seven regularly. For five interviewees, the dates and manner of entry were unknown. Some of those interviewed are not identified by name for their security or at their request.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed four representatives from civil society groups in Tunisia – the Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights (FTDES), Lawyers Without Borders (ASF), EuroMed Rights, and Alarm Phone, a rescue hotline network – as well as a volunteer who assisted refugees in Tunis; Elizia Volkmann, a Tunis-based journalist; and Monica Marks, a university professor and Tunisia expert. All seven had interviewed or assisted dozens of migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees in Tunisia, and knew of or had documented cases of abuse by the police or coast guard.

Among the migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees interviewed, nine had returned to their countries on emergency repatriation flights in March, while eight remained in Tunis, the Tunisian capital, or Sfax, a port city southeast of Tunis. Seven were among the up to 1,200 Black Africans expelled or forcibly transferred by Tunisian security forces to land borders with Libya and Algeria in early July 2023.

Overall, 22 interviewees had suffered human rights violations at the hands of Tunisian authorities.

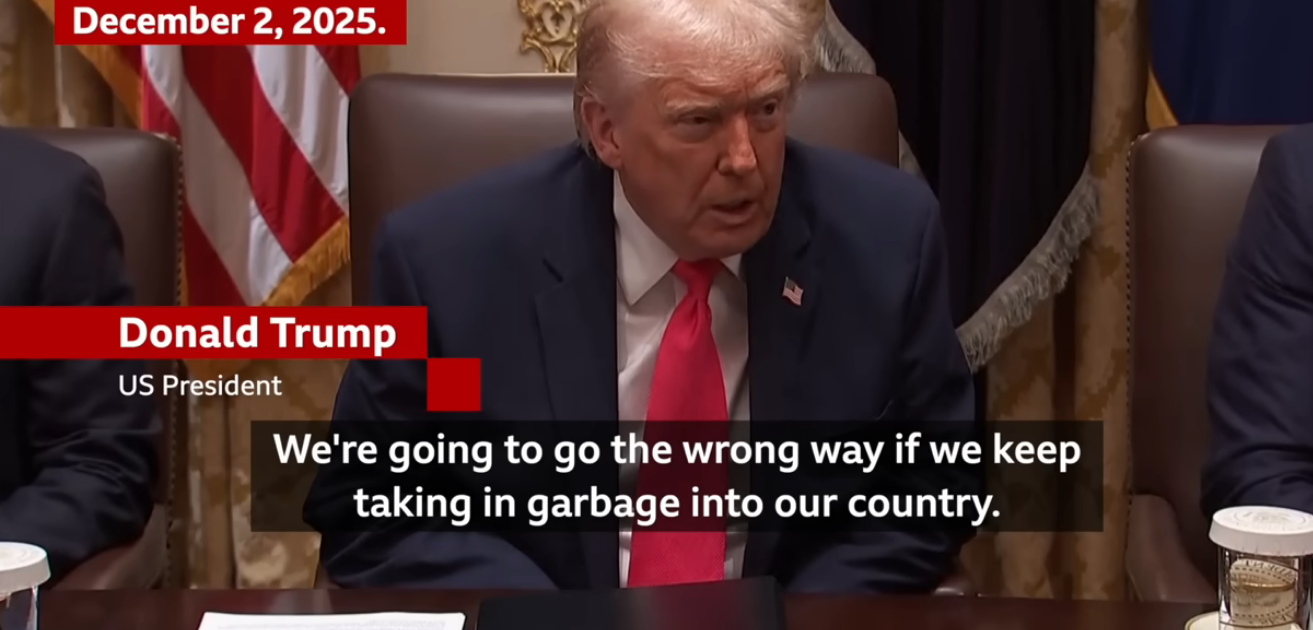

Though the documented abuses took place between 2019 and 2023, the majority occurred after President Kais Saied in February 2023 ordered security forces to crack down on irregular migration, linking undocumented African migrants to crime and a “conspiracy” to change Tunisia’s demographics. Saied’s speech, which UN experts have called racist, was followed by a surge in hate speech, discrimination, and attacks.

Fifteen people interviewed said they suffered violence by the police, military, or national guard including coast guard. This included a refugee and an asylum seeker beaten and electrically shocked by police during detention in Tunis. Five people said that authorities confiscated and never returned their money or belongings.

The seven interviewees expelled to border zones in July said the military and national guard left them in the desert with insufficient food and water. While some were relocated back into Tunisia a week later by Tunisian authorities, others still needed assistance or were unaccounted for.

At least nine people interviewed had been arbitrarily arrested and detained in Tunis, Ariana, and Sfax, where police profiled them based on their skin color. They said officers did not check their papers before arresting them, and in most cases neither conducted individual legal status assessments nor allowed them to challenge their arrest.

A 31-year-old Malian interviewed had a valid residence permit when police arbitrarily arrested him in mid-2022 in Ariana. “They didn’t ask me whether I had documents or not,” he said. “My friend was arrested with me … a Guinean military officer who had come to Tunisia for medical treatment. He had a passport with a [valid] entry stamp.”

Five people recounted abuses during or after sea interceptions and rescues near Sfax, apparently by the maritime national guard, also referred to as the coast guard. These included beatings, theft, leaving a boat adrift without a motor, overturning a boat, and insulting and spitting on survivors.

Three civil society group representatives interviewed also described increasingly problematic coast guard practices since 2022, including beatings, dangerous use of teargas, shooting in the air, taking or damaging boat engines and leaving people stranded at sea, creating waves that caused boats to capsize, delays in rescues, and theft of money and phones.

Human Rights Watch wrote to the Tunisian Foreign Affairs and Interior Ministries on June 28, sharing research findings and posing questions, but received no response.

In addition to the security force abuses, at least 12 men interviewed said they also experienced abuses by Tunisian civilians, including 10 assaulted or robbed and 5 forcibly evicted by civilian landlords. All but two incidents occurred after President Saied’s February speech.

In the months following Saied’s speech, and in the context of Tunisia’s deteriorating economic situation, worsening repression and xenophobic violence, and increasing boat departures and deaths at sea, over a dozen European officials visited Tunisia to discuss economic, security, and migration issues with Tunisian officials. The German interior minister noted the importance of “the human rights of refugees” and “creat[ing] legal migration routes,” but few others publicly mentioned human rights concerns. The French interior minister said France would offer Tunisia €25.8 million to help “contain the irregular flow of migrants.”

Millions in EU and bilateral funding – particularly from Italy – have already supported, equipped, and trained the Tunisian coast guard, “internal security forces,” and “land border management institutions.”

Border “externalization” – preventing irregular arrivals by outsourcing migration controls to third countries – has become a central plank in the EU’s response to mixed migration and has led to egregious human rights violations. Support to abusive security forces only exacerbates human rights abuses that drive migration.

“Both the EU and the Tunisian government need to fundamentally reorient their approach to migration challenges,” Seibert said. “Border control is no justification for trampling rights and ignoring international protection responsibilities.”

Migration and Refugee Context in Tunisia

Tunisia is a country of origin, destination, and transit for migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers. In the first half of 2023, it has surpassed Libya as a departure point for boats arriving in Italy. According to the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), of the 69,599 people who arrived in Italy between January and July 9 via Mediterranean Sea routes, 37,720 had departed from Tunisia, 28,558 from Libya, and others from Turkey and Algeria.

The most common countries of origin for those arriving in Italy were, in descending order, Côte d’Ivoire, Egypt, Guinea, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Tunisia, Syria, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, and Mali. Cameroon, Burkina Faso, Mali, and Guinea have faced widespread human rights abuses linked to conflict, coups, or government crackdowns in recent years.

A 2021 official estimate said that 21,000 foreigners from non-Maghreb African countries were in Tunisia, whose population is 12 million. The country hosted 9,000 registered refugees and asylum seekers as of January. Tunisia is party to the UN and African refugee conventions, and its Constitution provides for the right to political asylum. However, Tunisia has no national asylum law or system. UNHCR carries out registration and refugee status determination.

Though international human rights standards discourage the criminalization of irregular migration, Tunisian laws dating from 1968 and 2004 criminalize the irregular entry, stay, and exit of foreigners, as well as organizing or assisting illegal entry or exit. Penalties include prison and fines. Tunisia has no explicit legal grounds for administrative immigration detention, but multiple organizations have documented arbitrary detention of African migrants. Tunisia permits 90-day visa-free travel with an entry stamp for several African nationalities. However, obtaining a residency permit can be difficult.

According to the nongovernmental group FTDES, between January and May 2023, Tunisian authorities arrested over 3,500 migrants for “irregular stay” and intercepted over 23,000 people attempting irregular departures from Tunisia. FTDES spokesperson Romdhane Ben Amor told Human Rights Watch that most recorded arrests of migrants took place near the Algeria border, though hundreds also occurred in Tunis, Sfax, and other cities following the president’s speech.

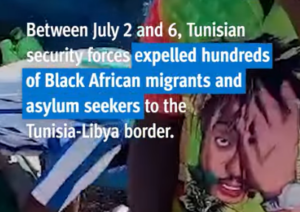

Collective Expulsion to Libya and Algeria Borders

Between July 2 and 5, 2023, Tunisian police, national guard, and military conducted raids in and around Sfax, arbitrarily arresting hundreds of Black African foreigners of many nationalities with both regular and irregular legal status. Without due process, the national guard and military expelled or forcibly transferred up to 1,200 people in several groups to the Libyan and Algerian borders.

The authorities drove an estimated 600-700 people south to the Libya border near the town of Ben Guerdane, according to five interviewees expelled there. They drove hundreds of others west to various locations along the Algerian border in the Tozeur, Gafsa, and Kasserine governorates, according to two expelled people, UN representatives, FTDES, and Alarm Phone.

The hundreds expelled to a remote, militarized zone at the Tunisia-Libya border included at least 29 children and 3 pregnant women. At least six were UNHCR-registered asylum seekers. People interviewed said that national guard or military officers beat and abused them during expulsions, including a 16-year-old girl who said she was sexually assaulted. They said security officers threw away their food, smashed their phones, and left them in a zone from which they could neither enter Libya nor return to Tunisia, with security forces of both countries pushing them back. They provided their GPS location on July 2-4 and videos and photos of expelled people, their injuries, smashed phones, passports, and consular and asylum seeker cards.

On July 7, Human Rights Watch interviewed two people expelled or forcibly transferred to or near the Algerian border on July 4 and 5. They were in two groups, totaling fifteen people, including seven women – two pregnant – and one child. They said they were transported from Sfax in buses, forced to walk in the desert without adequate food or water, and pushed back by both Algerian and Tunisian security forces. A Guinean woman asylum seeker shared her group’s GPS location in Gafsa governorate, while an Ivorian man shared his group’s location in Kasserine governorate. They also provided videos of their groups walking in the desert.

In a July 8 statement, President Saied called allegations of abuses by security forces against migrants “lies” and “fake news.” The weekend of July 8, Tunisian Red Crescent teams provided food, water, and medical aid to some migrants at or near the Algerian and Libyan borders. They were the only aid group Tunisian authorities allowed into the Libya border zone.

On July 10, Tunisian authorities finally relocated more than 600 people from the Libya border to International Organization for Migration (IOM) shelters and other facilities in Ben Guerdane, Medenine, and Tataouine, according to UN representatives and an Ivorian man among those taken to Medenine, who provided his location. However, on July 11, Human Rights Watch spoke with two migrants saying they were in a group of over one hundred expelled people still stuck at the Libya border. They shared videos and their location.

Migrants at both borders alleged to Human Rights Watch and others that several people had died or been killed following expulsion, though Human Rights Watch could not independently confirm their accounts. On July 11, Agence France-Presse reported that the bodies of two migrants were found in the desert near the Tunisia-Algeria border. Al Jazeera, who visited the Tunisia-Libya border area several times, published footage from July 11 showing two still-stranded groups of African migrants – over 150 people total – and the body of a migrant who had died.

Tunisia is party to the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination; to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, which prohibits collective expulsions; and to the UN and African Refugee Conventions, the Convention Against Torture, and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which prohibit forced returns or expulsions to countries where people could face torture, threats to their lives or freedom, or other serious harm.