Photos: YouTube Screenshots

(Tunis) – Tunisian security forces have collectively expelled several hundred Black African migrants and asylum seekers, including children and pregnant women, since July 2, 2023 to a remote, militarized buffer zone at the Tunisia–Libya border, Human Rights Watch said last week. The group includes people with both regular and irregular legal status in Tunisia, expelled without due process. Many reported violence by authorities during arrest or expulsion.

“The Tunisian government should halt collective expulsions and urgently enable humanitarian access to the African migrants and asylum seekers already expelled to a dangerous area at the Tunisia-Libya border, with little food and no medical assistance,” said Lauren Seibert, refugee and migrant rights researcher at Human Rights Watch. “Not only is it unconscionable to abuse people and abandon them in the desert, but collective expulsions violate international law.”

Between July 2 and 6, Human Rights Watch interviewed five people by phone who had been expelled, including an Ivorian asylum seeker and four migrants: two Ivorian men, a Cameroonian man, and a 16-year-old Cameroonian girl. Interviewees’ names are not used for their protection. They could not give an exact number, but estimated that Tunisian authorities had expelled between 500 and 700 people since July 2 to the border area, around 35 kilometers east of the town Ben Guerdane. They arrived in at least four different groups, ranging in size.

The people expelled were of many African nationalities – Ivorian, Cameroonian, Malian, Guinean, Chadian, Sudanese, Senegalese, and others – and included at least 29 children and three pregnant women, interviewees said. At least six expelled people were asylum seekers registered with the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), while at least two adults had consular cards identifying them as students in Tunisia.

People interviewed said they had been arrested in raids by police, national guard, or military in and near Sfax, a port city southeast of the capital, Tunis. National guard and military forces rapidly transported them 300 kilometers to Ben Guerdane, then to the Libya border, where they were effectively trapped in what they described as a buffer zone from which they could neither enter Libya nor return to Tunisia.

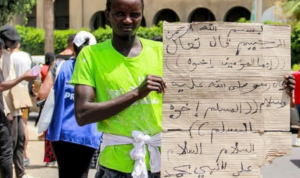

Tensions have been high in Sfax for months as Tunisian residents campaigned for African foreigners to leave, escalating to recent attacks against Black Africans and clashes with Tunisians. A man from Benin was killed in May and a Tunisian man on July 3. Videos circulating on social media in early July depicted groups of Tunisian men threatening Black Africans with batons and knives, and in other videos, security officers shoving Black Africans into vans while people cheered.

People interviewed said that Tunisian security forces had smashed nearly everyone’s phones prior to expulsion. They communicated with Human Rights Watch primarily through a phone that one man had managed to hide. They provided their GPS location on July 2 and July 4, as well as videos and photos of smashed phones; expelled people and their injuries, reportedly from security force beatings; and passports, consular cards, and asylum seeker cards.

Those interviewed alleged that several people died or were killed at the border area between July 2 and 5 – including, they said, some shot and others beaten by Tunisian military or national guard. They also said that Libyan men carrying machetes or other weapons had robbed some people and raped several women, either in the buffer zone or after they managed to cross into Libya to

look for food. No nongovernmental groups had access to the area, so Human Rights Watch could not independently confirm these accounts.

One video the migrants sent to Human Rights Watch showed a woman describing sexual assault apparently by Tunisian security forces. In another video, a woman says she had a miscarriage after the expulsion.

“We are at the Tunisia-Libya border, at the seaside,” said an Ivorian asylum seeker on July 4. “We were beaten [by Tunisian security forces].…We have many injured people here.…We have children who haven’t eaten for days … forced to drink sea water. We have a [Guinean] pregnant woman who went into labor … she died this morning … the baby died too.”

At the start of the expulsions, a group of 20 was dropped at the border the morning of July 2. Human Rights Watch interviewed two people in the group: a 29-year-old Ivorian man, and a 16-year-old Cameroonian girl.

The Ivorian man said that on July 1, police, national guard, and military personnel raided the house where they were staying – arresting 48 people – in Jbeniana, 35 kilometers north of Sfax. He said the detained people had entered Tunisia at various times, some regularly and some irregularly, but none he knew had passed through Libya. Tunisian authorities took the 48 people to a police station, examined their documents, and recorded their information. Security forces divided them into two groups, and drove the man’s group to Ben Guerdane, he said.

The man said they made stops at three bases in Ben Guerdane, and military or national guard officers “beat us like animals … punching, kicking, slapping, hitting us with batons,” and sexually harassed and assaulted the women, including groping them. “They started to touch me everywhere,” said the Cameroonian girl in the same group. “They slammed my head against their vehicle.”

The security forces threw away their food, smashed their phones, and left them at the border, the Ivorian man said. Two armed men in uniform from Libya later approached them and ordered them to return to Tunisia, he said, while on the other side, Tunisian military beat several men who sought to cross back to Tunisia.

Two men in a second expelled group, Cameroonian and Ivorian, said they and others had been arrested during raids on their houses in Sfax, on July 3 between 2 a.m. and 4 a.m., by police, national guard, and military. They said that authorities did not ask for anyone’s documents or record their personal information, though some were in Tunisia legally; instead, they drove them swiftly overnight to Ben Guerdane.

“We are from different countries of origin … and they brought us 300 kilometers from Sfax [to expel us] … instead of bringing us to Tunis, to our embassies,” the Ivorian asylum seeker said. “It’s inhuman.”

On July 5 and 6, authorities expelled a third and fourth group, each an estimated 200-300 people, from Sfax. Videos interviewees shared showed many injured people among the arrivals, with open wounds, bandaged limbs, and one with an apparently broken leg.

As of July 5, no humanitarian aid from the Tunisian side had reached the group, though the Ivorian man from the first expelled group said some uniformed Libyan men arrived that evening to provide some water and cookies for the children. But then on July 6, “The [same] Libyans … started to shoot in the air, burn things, chase us.… The Libyans told us to leave the territory and go toward the Tunisian side. They started to take out their guns to threaten us.”

On July 6, Human Rights Watch contacted representatives of the Tunisian Interior, Defense and Foreign Affairs ministries by phone, but was unable to obtain information.

President Kais Saied, in an inflammatory February speech that triggered a surge of racist attacks against Black Africans, had linked undocumented African migrants to crime and a “plot” to alter Tunisia’s demographic makeup. In a July 4 statement, Saied referenced “the criminal operation that occurred yesterday” in Sfax, referring to the Tunisian man’s killing, and said, “Tunisia is a country that only accepts people residing on its territory in accordance with its laws, and does not accept to be a transit or settlement zone for people arriving from numerous African countries.”

Tunisia is party to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, which prohibits collective expulsions, as well as the UN and African Refugee Conventions, the Convention Against Torture, and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which prohibit refoulement – forced returns or expulsions to countries where people could face torture, threats to their lives or freedom, or other serious harm. All countries should suspend expulsions or forced returns to Libya, given the serious harm people may face there. Governments should also not expel asylum seekers whose refugee claims have not been fully examined.

The Tunisian government should respect international law and conduct individual legal status assessments in accordance with due process before deporting anyone, Human Rights Watch said. The government should also investigate and hold to account security forces implicated in abuses.

Diplomatic delegations of African countries should seek to locate and evacuate any of their nationals expelled to the Tunisia-Libya border who wish to voluntarily return to their countries of origin, while the African Union Commission should condemn the abusive expulsions and press Tunisia to provide immediate assistance to affected Africans.

“African migrants and asylum seekers, including children, are desperate to get out of the dangerous border zone and find food, medical care, and safety,” Seibert said. “There is no time to waste.”