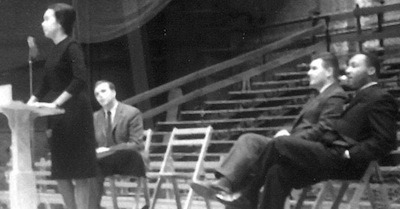

Marian Wright Edelman, John Maguire and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1961 at Wesleyan University

My dear friend Dr. John Maguire readily admitted his childhood in Montgomery, Alabama and Jacksonville, Florida didn’t make him a likely champion of racial equality. This is what he once said: “Up until I was 16 years old and a senior in high school, I did the same thing my friends did. We drove through the Black side of town throwing pears at Black guys and yelling racial epithets. We were the White oppressors. I was the White oppressor.”

But when he passed away recently at age 86, John—the president emeritus of Claremont Graduate University, former president of the State University of New York (SUNY) Old Westbury, and recipient of many accolades and honors—was widely respected as an extraordinarily committed advocate for civil rights and social justice. His story is a powerful example of the power and possibility of personal growth and change.

John described his parents as “radical segregationists,” although he also said they didn’t see themselves as “bigots” and believed there was a difference between the two. But he was a product of his place and time until that senior year of high school when everything began to change. He was chosen to go to an integrated YMCA baseball camp in Ohio where players were deliberately assigned roommates of other races. He remembered passing a soda around among his new group of friends and suddenly realizing it was the first time his lips had touched something a Black person’s lips had touched, a simple moment that shattered an imaginary taboo.

When he enrolled at Washington and Lee University the following fall, professors there slowly began to challenge his old racial assumptions. He attended a conference at Crozer Theological Seminary during his sophomore year where he was again assigned a Black roommate: Martin Luther King, Jr. Right away he found Dr. King and his ideas brilliant and compelling. It was the start of a friendship that lasted until Dr. King’s death and a relationship that influenced my friend John deeply as he was starting to change his own world view.

Throughout a Fulbright year in Edinburgh, divinity school and doctorate at Yale, and postdoctoral research at Yale, Berkeley, and in Germany and the Philippines, my friend John’s perspective kept broadening. Eventually, he didn’t just come to understand and accept the Civil Rights Movement in the South—he jumped in himself as a fervent ally and participant. This was true to who he was: a “happy warrior” ready to act justly.

In 1961 Dr. King encouraged him to join the Freedom Rides with his divinity school classmate and friend Dr. William Sloane Coffin, Jr. I begged to join them but they thought it too dangerous for a woman! I was furious having grown up in the South and having been jailed for sitting in at Atlanta City Hall’s cafeteria in 1960 without shields from Jim Crow. Life magazine featured John Maguire’s experience seeing the South’s violent racism from the other side and being arrested in Montgomery, his former hometown, for trying to order coffee at a bus station. He was eventually represented by the NAACP Legal Defense Fund’s Thurgood Marshall and Jack Greenberg and Yale Law professor Lou Pollak in a case that went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. By then John was a faculty member at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut. While many of his colleagues cheered him on and helped pay his fines and legal costs, some colleagues and alumni were deeply critical of his involvement in the Civil Rights Movement. But John was not turning back.

A few years later he helped Vincent Harding draft the historic antiwar sermon “

Beyond Vietnam” that Dr. King gave at Riverside Church on April 4, 1967, exactly a year before his assassination, warning America against succumbing to the “giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism, and militarism” and telling us we needed a revolution of values: “A true revolution of values will soon cause us to question the fairness and justice of many of our past and present policies. On the one hand we are called to play the Good Samaritan on life’s roadside, but that will be only an initial act. One day we must come to see that the whole Jericho Road must be transformed so that men and women will not be constantly beaten and robbed as they make their journey on life’s highway. True compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar. It comes to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring.”

Once John came to see that Jericho Road clearly, he spent the rest of his lifetime helping to “restructure” unfair structures. He told an interviewer he knew he’d made a difference during the Civil Rights Movement when he realized he’d opened his parents’ eyes. One day his mother said to him, “We see your friend Martin King on TV all the time, and he looks so tired. Tell him that if he wants a place to rest…he can rest here. We won’t bother him.” When he heard her say that he wept. After Dr. King was killed John became director of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Center for Social Change, and throughout his life he kept helping transform people’s points of view—especially the generations of students whose lives he touched and who learned from his example as president of SUNY Old Westbury from 1970-1981 and then Claremont Graduate University from 1981-1998.

My friend John fought passionately for increasing diversity in and access to higher education throughout his life and remained convinced that solving the problem of access to higher education had to start long before students entered the doors of a university or graduate school. He also knew that the problem was much wider than education and spoke out against disparities in health care, the criminal justice system, economic development and more.

John and his extraordinary wife Billie were loving and faithful friends and unceasing supporters of the Children’s Defense Fund and other organizations and people who, like them, wanted to help bend the arc of the universe towards justice. At every step he did it with a trademark sense of joy and with his beloved Billie and their daughters and grandchildren at his side. Bill Moyers and his wife Judith were close friends of the Maguires, and Bill said the words that come to mind when he thinks of John are “Passionate heart. Searching intellect.” Judith added: “Scarred by tragic losses, John managed to find abundant joy in life as a priceless friend and fearless leader…and [Billie’s] support of John through thick and thin was central to his ability to do all that he did.” At a dinner party many years ago John was reportedly asked what he would want his epitaph to be, and answered: “He had a passion for justice and excellence and he was steadfast.” No words better sum up his marvelous legacy. And like him, we and our nation must embrace his lessons, example and bold willingness to change to ensure a more just nation and world fit for all God’s children.

Marian Wright Edelman is President of the Children’s Defense Fund whose Leave No Child Behind® mission is to ensure every child a Healthy Start, a Head Start, a Fair Start, a Safe Start and a Moral Start in life and successful passage to adulthood with the help of caring families and communities. For more information go to www.childrensdefense.org