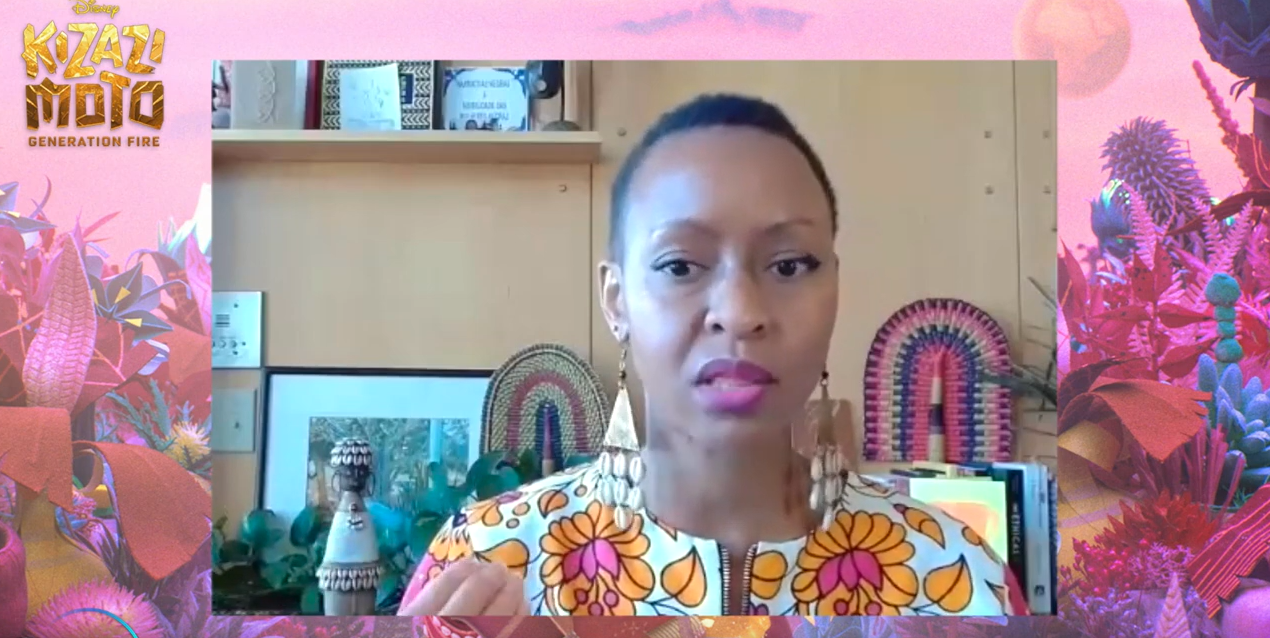

Photo: Ethiopian Orthodox Christian monk Aba Gebreselassie explains how he fled when the TPLF invaded Waldeba Monastery in Amhara Region, Ethiopia. University of Gondar Professor Menychle Meseret Abebe listens and translates. (Photo credit: Alastair Thompson)

Barring anything unforeseen, these will be my last notes from Ethiopia for now. I have been in the Horn of Africa—specifically Ethiopia and Eritrea—for nearly two months. That’s far longer than I’d expected to stay, thanks to all the kind people who offered to host and facilitate my efforts, so that I could see and report more. I wouldn’t have been able to do this without them or without my traveling companions at various stages, US photojournalist Jemal Countess, Ethiopian American multimedia journalist Betty Sheba Tekeste, and Scoop-New Zealand journalist Alastair Thompson, whose insights and photos have all appeared in my reports. Their Twitter accounts are well worth following.

As I scroll through my cell phone snapshots, I come across one taken several days ago from the back seat of a bajaj, aka “tuk tuk,” one of the three-wheeled blue taxis in service all over Ethiopia. Drivers decorate these vehicles with their favorite decals, including the phrases “#NoMore” and “It’s My Dam,” images of Ethiopian Emperors Menelik and Tewodros, and the image of Bob Marley. The driver of this bajaj had affixed a red, green, and gold “RASTA” decal to one side of his front window and a red, green, and gold cannabis leaf decal to the other. Emperor Haile Selassie gave land to a Rasta community in Ethiopia, but smoking the sacred herb is still illegal. This is one of many things I still don’t understand here.

On every leg of the trip I’ve asked myself whether I really understand anything, though I’ve also reminded myself that any self-respecting journalist should. English is the most widely spoken foreign language in Ethiopia, but I’ve often relied on translation from Amharic, the most widely spoken Ethiopian language, and at times on translation from Afar to Amharic to English. Eighty indigenous languages are spoken in Ethiopia, as many as in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The state-owned Ethiopian News Agency (ENA) transmits news in the two most widely spoken domestic languages, Amharic and Oromiff, and plans to transmit in Tigrinya, Harari, Wolayetegna, Sidamegna, and Afari. It also transmits news in English, Arabic, and French, and plans to transmit in Kiswahili.

When I called ENA reporter Muse Mulessa to double-check that, he reminded me that I’d promised him speakers’ lists for the Sanctions Kill Coalition and the Black Alliance for Peace .

The Abay River and the unifying force of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam

On our way to Bahir Dar for a University of Bahir Dar conference on Ethiopia since 2018, Alastair Thompson and I flew over Lake Tana, the source of what we thought was the Blue Nile River. Lake Tana and the river are both muddy, heavy with sediment, so I asked why the river is called “the Blue Nile” and learned that Ethiopians don’t call it that; it’s the Abay River to them. It becomes “the Blue Nile” only after crossing into Sudan, where it joins the White Nile to become the Nile before crossing into Egypt. It seems that in Sudan the water level is so high during flood times that the river changes color to almost black and, in the local Sudanese language, the word for black is also used for blue.

Egypt claims to own every last drop of Ethiopia’s Abay River because it flows into what they call the Nile and some moldy British colonial treaty deeded all waters flowing into the Nile to them. On these flimsy grounds, Egypt bitterly opposed construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) on the Abay River, just before it flows into Sudan and becomes the Blue Nile. Tension between Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia over the dam continues, but the dam is built, it began generating electricity in February this year, and the third filling will get underway soon, during the June-to-September rainy season.

Ethiopia’s hopes are heavily invested in the GERD. It’s a source of great pride that Ethiopians and the Ethiopian diaspora have financed its construction by purchasing bonds. Chinese interests are building the electricity delivery infrastructure, and at the outset of the TPLF war, Chinese and Ethiopian officials met to discuss protecting this and other Chinese investments.

Ethiopians are struggling to overcome the enormous damage done during the TPLF’s 27-years of divide-and-rule ethnic politics, backed by the US, and I haven’t seen anything that unites them more than the GERD. An Egyptian engineer, quoted in Al Monitor , described this strength from sore loser Egypt’s viewpoint: “The latter [Ethiopia] is exploiting the GERD project politically at the domestic level, claiming it is a national project unifying all Ethiopian ethnic groups.”

“Because it is! And it will!” said one of my hosts. “Ethiopians at every level leaped to invest in the dam. Even poor Ethiopians working in the Arab countries saved their money to invest in the dam. An attack on the dam would be like the Italian invasion that stirred Ethiopians to unite behind Emperor Menelik to win the Battle of Adwa in 1896.”

Everyone expects the TPLF to escalate the war again soon but not without US support

After the government declared a unilateral, humanitarian ceasefire at the end of December, the TPLF continued its attacks on the 1600-year-old Waldeba Monastery in Amhara Region, displacing 1000 monks. In Gondar, Amhara Region, Alastair and I interviewed a young monk who said the TPLF had demanded to know the positions of the Ethiopian military, the Amhara Special Forces, and the FANO militia, and then refused to accept the monks’ answers that they were not military men, but men of God. He said he had fled while the TPLF fired bullets after him, then jumped into a river to escape.

The Waldeba Monastery is spread out over a very wide area, including forests and caves. The displaced monks say that, with 75% of the monks gone, the TPLF have established a military base, which could be used for a new TPLF offensive into Amhara Region from the east.

Just before the government’s December ceasefire, the TPLF invaded Afar Region, shelling towns indiscriminately and displacing hundreds of thousands of Afar tribespeople, seemingly in an effort to once again threaten the Addis-Djibouti transport corridor, which is both a highway and railway line. However, Afar tribesmen, with some help from Ethiopian Air Force drones, drove them back inside the borders of Tigray Province roughly four weeks ago.

Fighting has been sporadic since, but in early May, the TPLF attacked the Eritrean Army at Badme, resulting in reported but as yet unconfirmed counterattacks.

Everyone we spoke to expects the TPLF to escalate again soon when June rains make it more difficult for the Ethiopian Air Force to operate its drone force. Many believe that TPLF forces amassed in Sudan may try to invade over Amhara Region’s western border.

Despite US declarations that all warring parties are responsible, no one we spoke to believes that the TPLF could keep fighting without the political, diplomatic, and most likely material support of the US, which may include pending sanctions.

I wish I could conclude on a lighter note, but summoning Gramsci’s “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will,” I can only resolve to share what I’ve learned back home and suggest that the US let Ethiopia live.

Ann Garrison is a Black Agenda Report Contributing Editor based in the San Francisco Bay Area. In 2014, she received the Victoire Ingabire Umuhoza Democracy and Peace Prize for her reporting on conflict in the African Great Lakes region. She can be reached at ann(at)anngarrison.com .