Photo: Screenshot

Talk of independence and self-determination is being heard with greater frequency and with higher volume in Black American areas of influence.

Increasingly, Black Americans are concluding that, no matter how purposeful and intensive our efforts, our progress toward achieving income and wealth equality remains abysmal.

We recall pre-racial integration (pre-mid-1960s) times and realize that conditions during the segregated and Jim Crow Era were, in some ways, better than conditions today—especially for certain aspects of the economic front.

These two realizations motivate an idealized vision of returning en masse to segregated areas of influence where we can employ our knowledges, skills, abilities, and rights to build solid areas of influence that have certain benefits available in an integrated world, but that also reflect the independence of a self-owned and self-determined socioeconomic system. Prospects for realizing this vision are considered with or without Reparations.

This segregated socioeconomic system would be absent racial discrimination and exclusion and the related anxiety, stress, and pressure, which kill. While income and wealth inequality would remain in these self-determined Black areas of influence at least initially, in time and with the return of an Afrocentric and communal culture, it should be possible to reduce economic inequality within Black America.

All of Black America could rise together.

Let us imagine that this is, in fact, what Black America comes to desire. Such a desire raises the question: How can Black America build self-sufficient, self-sustained, and self-determined areas of influence?

To become independent, Black America must produce for our consumption.

In reality, production for our own consumption will present challenges, but with sufficient time and resources, and considering that we are employed in most key industries and occupations currently, we can grow to produce to meet our needs.

Given our cultural capital, and to avoid dramatic changes in consumption patterns, it is likely that we will replicate, to some extent, much of what is produced for the US market today. In otherwords, with differences in quality and quantity, Black America might initially develop an independent economy that is somewhat similar to the US economy.

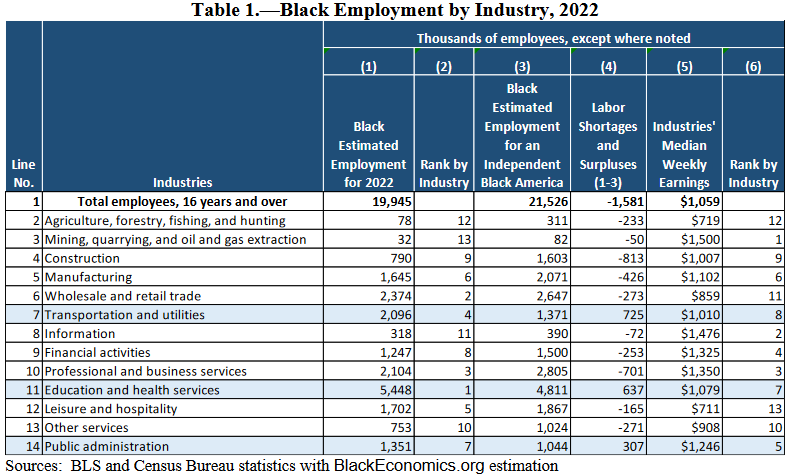

Table 1, (ABOVE) which is based on US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics and US Department of Commerce, Census Bureau statistics, shows: Black estimated employment by industry (column 1); the related industry ranking (column 2); Black estimated employment for an independent Black America (column 3, estimated by applying industry employment per capita ratios for the US in 2022 to the Black 2022 population); labor shortages (negative values) and surpluses (positive values) for an independent Black America (column 4); median weekly earnings by industry (column 5, for all races and ethnicities); and the related ranking of industry earnings (column 6). Table 1 reveals that an independent Black America would experience labor shortages for most industries, but there would be labor surpluses for three industries: Transportation and utilities, Education and health services, and Public administration.

This brings us closer to a discussion of the title of this analysis brief.

A seldom stated reality is that Black America has gravitated to the just-cited three industries for a variety of historical and cultural reasons. However, there is a thread that connects the three industries: They are influenced significantly by government financial support and regulations that cause the industries to adhere closely to unbiased employment requirements that are embodied in anti-discrimination laws.

For example: The Transportation and utilities industry includes urban transit operations and the US Postal Service (both represent sizeable governmental enterprises); the Education and health services industry includes public elementary, secondary, tertiary institutions, and hospitals, which are financed largely by government; and the Public administration industry covers the full scope of governmental operations.

It is also worth noting that these three industries reflect the following ranks with respect to the size of Black American employment: Transportation and utilities 4th; Education and health services 1st; and Public administration 7th.[1] In addition, these industry groups have the following ranks in median weekly earning (for all races and ethnicities): 8th; 7th; and 5th, respectively.[2] These middle-and-below weekly earning rankings, nevertheless, cause workers in these three industries to experience median weekly earnings that are nearly twice the poverty line income for a family of four for 2022, which is $534 weekly.[3] Admittedly, the median weekly earnings for Black Americans are likely to be somewhat less than those cited for all races and ethnicities.

Acknowledging that government is an important financial and regulatory source for these three industries forces us to awaken to the fact that a sizeable proportion of Black labor is closely tied to government.[4] Moreover, we should not forget that, as reported for Black American retirees in 2017, Social Security benefits accounted for over 50 percent of income for 56.9 percent of retired households, and for over 90 percent of income for 32.5 percent of retired households.[5] It is difficult to ascertain how many of the remaining Black retired households count on government pension benefits as an important source of income. Also, keep in mind that we have not touched on the number of Black Americans who receive other social benefits from the government.

Understanding how the American government works, we certainly recognize that to pursue liberty is to cut ties with the government. Fearing an inability to secure food, clothing, and shelter without sufficient financial resources after cutting ties with the American government, some Black Americans may balk at seizing liberty. Stated another way, some Black Americans are likely to fail to act to take liberty due to a reliance on American government financial support.

Is the just-described situation a show-stopper? It certainly could be. But only if Black leadership fails to: (1) Build a strong case for independence, self-determination, and freedom showing that the benefits far exceed the costs; (2) show Black America that there is a plan to address an absence of financial support from the US government that has a reasonable probability of success; (3) unify Black America around Afrocentric communalism; and (4) organize economic activity in Black areas of influence that will employ our labor to produce the goods and services that we need.

Black American liberty means cutting a lifeline. History is replete with people who have cut their lifeline and gone on to enjoy the benefits of their liberty. It is not that they did not incur certain hardships after cutting the lifeline. But they decided before they undertook the seizure of their liberty that they would rather die free than continue to exist in a scenario that guaranteed their bondage and that of their posterity into perpetuity.

As noted at the outset, talk of self-determination is increasing in Black America—like never before. This analysis brief is intended to remind us that steps to seize liberty means lifelines will be cut. Whether we move beyond talk to action will signal our willingness to cut those lifelines.

What we know is that the sooner we are prepared to cut lifelines, then the sooner we can become free. There is no day like today to start preparing to cut lifelines.

Dr. Brooks Robinson is the founder of the Black Economics.org website: https://blackeconomics.org/index.php/about-us/

References:

[1] US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics (2023), “Household Data Annual Averages, 18. Employed persons by detailed industry, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity,” Current Population Survey; https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat18.htm (Ret. 020923).

[2] US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics (2023), “Table A-27. Usual weekly earnings for employed full-time and salary workers by detailed industry and sex, Annual Average 2022,” Current Population Survey. These are unpublished statistics that were obtained on February 8, 2023 from BLS by email message.

[3] Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, US Department of Health and Human Services (2022); https://aspe.hhs.gov/topics/poverty-economic-mobility/poverty-guidelines/prior-hhs-poverty-guidelines-federal-register-references (Ret. 021023).

[4] The three cited industry groups account for nearly 45 percent of estimated Black employment for 2022.

[5] Irena Dushi, Howard Iams, and Brad Trenkamp (2017), “The Importance of Social Security benefits to the Income of the Aged Population,” Social Security Bulletin, Vol 77, No. 2; https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v77n2/v77n2p1.html (Ret. 021023).