By Michael Waldman\Brennan Center

Photos: YouTube Screenshots\Wikimedia Commons

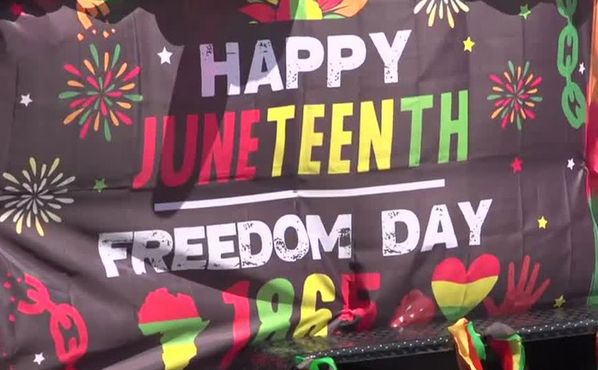

Tomorrow, the nation celebrates Juneteenth. It was officially recognized as a national holiday only four years ago, during the racial reckoning after George Floyd’s murder by police. We are still feeling our way through what the holiday means for the nation.

![]()

Juneteenth commemorates the long-delayed emancipation of the last enslaved Americans. After the Civil War, in which 200,000 Black men fought in the Union Army to defeat the Confederacy, word of this new birth of freedom did not reach Galveston, Texas, until months later. An army general stood on a hotel balcony and proclaimed “absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves.”

In one sense, then, Juneteenth celebrates the triumph of the Black community over historic oppression, and the nation’s second revolution. Once mostly a regional holiday, it was a time for celebration and optimism. Now recognized as a national holiday, it renews our dedication to achieving equality — the struggle to surmount the flawed origins of our country and live up to our loftiest and most challenging ideals.

But we won’t do justice to Juneteenth if that is all we do. It reminds us of the need for action. There has been great progress, but far too little after centuries of struggle. Discriminatory bank lending practices have led to residential segregation and economic inequality that compounds generation after generation. The profound racial imbalance in our criminal justice system is a disheartening indicator of how far we have to go.

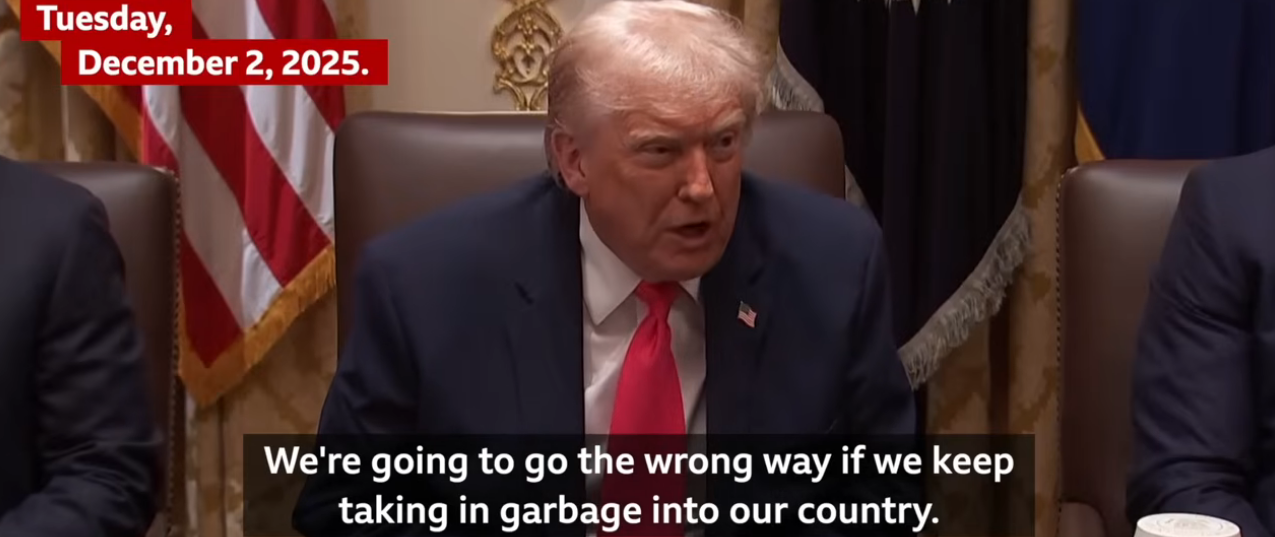

At the Brennan Center, we focus especially on access to our political system. The United States only achieved a multiracial democracy when the Voting Rights Act became law in 1965. (In that sense, our democracy is younger than that of many other nations.) For decades, the gap between the participation rates of white and nonwhite voters narrowed; it eventually closed entirely. But then something changed for the worse. Brennan Center social scientists recently analyzed nearly 1 billion voter records. The racial turnout gap, they found, has widened all over the country since 2008 for many reasons. In the states once covered by the strongest protections of the Voting Rights Act — before the Supreme Court gutted it in 2013 in Shelby County v. Holder — the turnout gap has grown twice as fast as it has elsewhere. Voter suppression laws, plainly, have suppressed the vote.

These moves to squelch participation are not limited to the rules for casting ballots. Entrenched white politicians have found it easy to draw district lines to curb the electoral power of Black and Latino voters. As our study suggested, this practice is often most destructive in the South, where the population is rapidly diversifying but representation lags far behind. It’s one reason why the Brennan Center is expanding our work in the region.

Which brings the story back to Galveston, Texas. As my colleague Kendall Karson Verhovek recounts, county officials have “carved up the sole majority district for Black and Latino voters and scattered them across the other three.” Subtle but effective, racial gerrymandering like this can dilute political power as efficiently as the most egregious voting rule. Civil rights groups have challenged the unfair map.

Now the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit is considering the claim that Black and Latino voters cannot jointly sue on their own behalf, which is the basis for many of the lawsuits brought by voters and civil rights groups. That’s absurd — it would mean that the Supreme Court never noticed that numerous rulings over the years relied on an imaginary right. This reactionary claim won’t likely become law.

But the fact that a court would consider this — in a story from Galveston, of all places — shows why Juneteenth is a vital holiday. A promise of equality was made at our nation’s founding, and we rightly celebrate the declaration that all are created equal on the Fourth of July. Juneteenth celebrates a step toward the fulfillment of that promise, when Black Americans went from being considered three-fifths of a person under the law to full citizens. Juneteenth does not merely look fondly to the past but celebrates our fitful progress toward becoming the country that our founding documents envisioned.