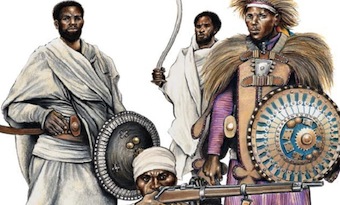

Photo from Sean McLachlan’s “Armies of the Adowa Campaign 1896.”

“Ebalgume! Ebalgume!” or “Reap! Reap!”–Ras Mikael, one of the generals aligned with Emperor Menelik, urging his soldiers to cut down the Italian army as he led them into battle.

The narrative of European military invincibility was again disrupted by Ethiopia’s spectacular victory over Italy at the great Battle of Adwa in 1896.

A huge Ethiopian army under the command of Emperor Menelik II, Empress Taytu Betul, and a host of Ethiopian princes annihilated an army of 17,000-strong commanded by five Italian generals and other senior officers. The heavily equipped Italian army included thousands of Eritrean fighters; Eritrea was then under Italian control.

What led the two nations to the battlefield was Italian treachery. Italy had concluded the Treaty of Wuchale, or Uccialli as the Italians spelled it, with Emperor Menelik in 1889. The treaty gave Menelik the “option” to use Italy as an intermediary in dealings with other European powers. However, the Italian version of the treaty’s article XVII —unlike the one in Amharic that Menelik retained—actually made Ethiopia an Italian protectorate. When Menelik discovered the deceit, he rejected the agreement. The result was inevitable war. Menelik was a wise ruler and also had the counsel of his remarkable wife, Empress Taytu. The Emperor remembered how a huge British invasion army led by Gen. Robert Napier, equipped with modern weapons, crushed the Ethiopian emperor Tewodros II’s army in 1868 at the battle of Magdala. Tewodros ended up dead, his castle was burned to the ground, and his seven-year-old boy Prince Alemayehu was kidnapped and taken to Britain where he died, homesick, in 1879. Menelik was not about to repeat Tewodros’ mistake. He used the next six years to build up his army’s arsenal of modern weapons.

The Italians, under Prime Minister Francesco Crispi, were emboldened by earlier victories in the region, as documented in The New York Times. In 1890 Crispi sent an invasion force that conquered Eritrea and other territories that were also claimed by Ethiopia. On that occasion, The New York Times published a triumphalist account of this war of aggression. “THE ITALIANS IN AFRICA: RESULTS OF A CRISPI’S BRILLIANT POLICY,” The Times proclaimed in the headline of a February 2, 1890, article lauding the invasion. “DECLARATION OF A PROTECTORATE OVER KING MENELICK’S DOMAINS—EUROPE’S ASTONISHMENT,” the headline concluded. The article was a melodramatic celebration of European imperial assaults on Africa. Italy, according to the Times article, “had achieved triumph upon triumph in Africa,” and there had been a surrender by “all the tribes.” The Italians had defeated Ras Alula Engida, a renowned general who was referred to by European writers as the “Garibaldi of Abyssinia,” a reference to Giuseppe Garibaldi the famed general and politician who fought in the many wars leading to the unification of Italy in 1871.

During that earlier campaign, when the Italians occupied Adwa in northern Ethiopia after penetrating from Eritrea, the Times February 2, 1890 article claimed “the natives” welcomed them as liberators. “Europe now marvels and perhaps scarcely credits its own eyes. Italy in Adowa!” the Times article continued. “Is it true or is it a dream? Nothing in the world has the power to drive the Italian troops from their central position.” Still, the editors must have realized that even at the height of nineteenth century European Imperial conquest of Africa, it was highly hypocritical for a leading newspaper in a “democratic” society to blatantly endorse brutal, unprovoked aggression—even if the victims were mere “savages,” as the Times elsewhere described the Ethiopians.

So the article offered moralistic rationalization to justify the invasion. The Times invoked The White Man’s Burden—the alleged duty to civilize the “natives” that European colonizers invariably proclaimed as they seized territory in many parts of Africa. “We could not thus speak, however, if the program of Italy in Africa was one of pure conquest, because exploits exclusively military are in too great opposition to the sentiments of progress, of peace, of work, of companionship, that should form the pivot of modern life,” the article claimed. “But instead, we may rejoice in and applaud this conquest of civilization and Christianity over barbarians and savages, over unbelief, over habits of ferocity, over brutal ignorance of every human law, religious, social, and civil.” These assertions about Ethiopia were of course hollow; Christianity became the country’s official religion in 330 A.D. Toward the end of the Times‘ article celebrating conquest, the true motives behind Italy’s aggression finally emerged, in words that succinctly summed up the reasons behind Europe’s entire imperial assault on the continent: “The water roads of Africa and the large commercial arteries in the hands of Italy signify that they are also in the hands of the civilized world, which can now introduce, without fear, the benefits of commerce, of exchange, of relations of any and every sort, and in short time, produce the best profits from the immense natural wealth existing there.”

The celebration was premature. When Italy finally moved to conquer all of Ethiopia in 1896, Menelik II was now prepared. He had mobilized a sizable army and had imported arms, including artillery, from Russia. The dispute over the Treaty of Wuchale was finally resolved on the battlefield. The fighting started at 6 a.m., on March 1, 1896, and by noon, it was all over for the Italians.

This time around, the good newspaper, The New York Times, offered a mournful tone. “ITALY’S TERRIBLE DEFEAT,” the Times proclaimed, in the headline of a March 4, 1896, article about the Battle of Adwa. Of course, there was nothing terrible about this decisive confrontation for the Ethiopians. Menelik and his wife, Empress Taytu Betul, led their forces into combat; the empress herself commanded an army of 6,000 men.

Menelik’s combined armed forces comprised an alliance of princes who were often at war with each other. The Italians united them against a common foe; European invaders. One of Menelik’s commanders, Ras Mikael, reputedly yelled “Ebalgume! Ebalgume!” or “Reap! Reap!” as he plunged with his soldiers into the Italian lines. Ras Alula Engida, one of Menelik’s leading commanders, now avenged his earlier defeat at the hands of the Italians. The overall losses inflicted on an original invading army of 17,000 were staggering: 2,918 Italian non-commissioned officers and men were killed; 2,000 African soldiers from Eritrea, or askaris, fighting for Italy were killed; 261 Italian officers were killed; 958 askaris and 470 Italians were wounded; 954 Italian soldiers were permanently missing; and, 56 cannons and 11,000 rifles were captured. The dead included two Italian generals, Giuseppe Arimondi and Vittorio Dabormida; Major Gen. Matteo Albertone was captured. Many of Menelik’s generals wanted the Ethiopian army to pursue the panic-stricken Italians and wipe out survivors as they fled toward Eritrea. Menelik knew the cost of provisioning his own large army if the conflict became protracted. He rejected the recommendation.

Italians could not comprehend what had happened in Africa and the national establishment refused to accept the defeat. Instead, the campaign’s commander-in-chief, Gen. Oreste Baratieri, was blamed for “poor military strategy” by the Italian government and newspapers. Every possible excuse was entertained. The Italians refused to credit the Ethiopians with military genius. The Ethiopians suffered heavy losses too. But it was their country and they were willing to make sacrifices to defend it. The New York Times reported that reinforcements from Italy were to be quickly sent to Africa. Political conditions were so grave that Pope Leo XIII canceled a major diplomatic banquet to celebrate the anniversary of his coronation. The Italian government was destabilized by the defeat, the Times reported, and its survival was in jeopardy. “The present campaign against the Abyssinians threatens to become one of the most disastrous in which the Italian arms have ever taken part,” the Times reported, “and what the final outcome will be, it would not be hard to predict.”

The New York Times article added, “Among the many reports current today was one to the effect that Gen. Baratieri had committed suicide, being unable to endure the humiliation of his defeat.” This turned out to have been an inaccurate report. Baratieri led the flight after the rout, losing his pince-nez in the process.

Italian citizens, indeed, most Europeans, were simply incapable of conceptualizing what had occurred in what they had been taught was “darkest” Africa. All the racist literature and myths about White Supremacy they had consumed had never hinted at the possibility of such a catastrophe. Ethiopia’s victory undermined, at least for some time, the lessons Italians had been taught about the African’s inherent inferiority. What made the defeat even more difficult for Italians to comprehend was that, during a visit to Rome before the decisive battle, Baratieri, who was also governor of Italian Eritrea, had been awarded the Order of the Red Eagle. Baratieri, too, on that occasion, was compared to Garibaldi. The Italian general asked Parliament to approve more funds so that he could “annihilate” the Ethiopians. He boasted that he would return with Emperor Menelik inside a cage. Italian journalists stoked the national bloodlust by endorsing the imperial project in newspaper articles; much in the same way that British newspapers had encouraged Gladstone to send Gordon to the Sudan twelve years earlier. However, when Baratieri returned to Africa, the “savages” refused to cooperate. Menelik, riding on horseback, exhorted his troops. Empress Taytu unleashed her reserve army. In the end the Ethiopians tamed the European general.

Baratieri was court-martialed by the Italian military for “cowardice.” He was, however, acquitted.

The Ethiopians marched the captured Italian soldiers, forcing them to walk hundreds of miles back to the capital city founded by Empress Taytu, Addis Ababa. Many of them perished along the way and survivors were jeered and spit on by Ethiopian women as they finally limped into the capital, where, in another turning of the tables, many were put to work on public projects for many months under the supervision of Africans.

The Italians had been defeated in wars before Adwa; but never before by Africans. Riots broke out in the streets of Rome. Perhaps there were some fears that the Ethiopians would pursue the routed troops back to Italy, to invade, ransack, and even occupy their capital.

Eventually, the Italian government collapsed. The war officially ended with the Treaty of Addis Ababa, which also annulled the Treaty of Wuchale, on October 26, 1896. The Ethiopians forced Italy to pay several millions of Lira in compensation before releasing the prisoners of war the following year.

Adwa was one of the greatest victories against European imperialism and White Supremacy in Africa.

Note: This essay is excerpted from my book “The Hearts of Darkness, How White Writers Created the Racist Image of Africa,” (Black Star Books, Second Edition). The book is being revised to be released again May, 2019. Last year when I wrote about Black Panther in a commentary on Black Star News, I said the Adwa victory represented the Real Wakanda. I’m happy to announce that the commentary I wrote now appears in a newly-released book “Black Panther: Paradigm Shift or Not? A Collection of Reviews and Essays on the Blockbuster Film,” edited by Herb Boyd and Haki Madhubuti. I’m also working on a graphic book about the Battle of Adwa that’s being illustrated by my 12-year-old niece Aly and a screenplay. Aly’s mom, my sister Doris, staged her play “Empress Taytu Betul” in the U.K. on March 1, 2019.