Driving the dark highway to Selma, Ala., I met forgotten heroes of the voting rights movement.

It was the night before President Barack Obama’s arrival. I was driving toward that infamous bridge when a small church, on the side of Highway 80, pulled me from the road.

This part of Lowndes County, Ala., is known for farming, poverty, religion, and the Edmund Pettus Bridge. It should be remembered for playing a crucial role in civil rights history.

Mt. Gillard Missionary Baptist Church, a red brick building surrounded by gravel for make-shift parking, was warm on a cold night.

Standing inside the front doors, with a local sheriff, restless young people, and others for whom there were no more seats, I listened as the history of Lowndes County’s civil rights movement was read aloud.

Sister Ruby Randolph’s passion local history made up for her stumbles over names and dates. The information she read should be recorded in history books.

Lowndes County was notorious in 1965. As in Dallas County, where Selma is located, African-Americans in Lowndes were threatened with assault and murder for attempting to register to vote.

The right to vote by law did not ensure access to the voting booth. Without that access, Black residents could not change the power structure. Law and law enforcement remained in the hands of White power-brokers who brutalized Blacks with impunity.

Yet, Lowndes County would play a key role in the civil rights Movement. As detailed in his book “Bloody Lowndes” by Dr. Hasan Jeffries, it was here that the Black Panther Party began.

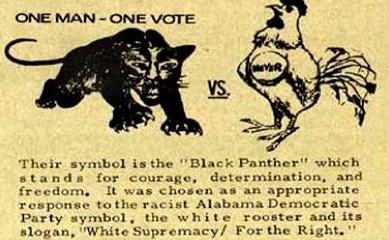

The Black Panther Party was a political party formed as an alternative to the Democratic and Republican parties that refused Black voters. The Democratic symbol was the rooster.

A fierce counter-symbol, the panther, was chosen to defy terrorist threats by the Ku Klux Klan and to help illiterate residents correctly select Black candidates who were bold enough to run for office.

Although Lowndes County was a bastion of White supremacy Black residents spurred activists nationwide to fight for civil and human rights in new and more radical ways, says Jeffries.

It was this radicalism that drew Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to this rural poverty-stricken region.

When Jimmie Lee Jackson was murdered on Feb. 18 by a White Alabama state trooper in a town nearby, Dr. King and the SCLC chose to march from Selma to Montgomery, the state capitol, 54 miles away, in protest, on Sunday, March 7.

White Alabama state troopers attacked them with horses, nightsticks, and tear gas as they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge. That attack made international news and pushed President Lyndon B. Johnson to demand Federal voting rights protections for African Americans.

The Voting Rights Act was signed into law on August 6, 1965.

Now, 50 years later, the bravery of those foot-soldiers in Lowndes County has been overshadowed by the events on that bridge. Few recall Tent City, a settlement created in 1965, on Black-owned property, near Route 80, for sharecroppers who were thrown off out of their homes for participating in voting rights protests.

Lowndes resident Timothy Mays, then a member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and Black Panther Party helped those Tent City residents and the marchers on Dr. King’s journey to Montgomery.

Forgotten are the Lowndes County political candidates of those treacherous days who could have been murdered for daring to challenging White office-holders.

Alice Moore, not only ran for Tax Assessor, back then, but her platform was “tax the rich to feed the poor.” In Mt. Gillard Church, the night before over 30,000 people would descend upon Selma, the forgotten activists from local plantations sat with those who had integrated Lowndes County Public Schools and Hayneville High School.

Black business owners who suffered financial losses due to their activism listened with past Tent City residents as Pastor Courtney D. Meadows, 21, spoke with an inspiring determination well beyond his years or civil rights experience.

“God put Lowndes County in the right place and time for the Civil Rights Movement,” Pastor Meadows said. “We have a wall of Jericho called racism, fortified by Jim Crow laws. They have been building that wall since slavery. But, we are going to tear that wall down.”

I asked Roy Managan, about 70, and slightly stooped, who stood near me watching from the doorway of Gillard Church, what he thought about Lowndes County’s forgotten role in these Selma events.

“I still want to work with them [the U.S. Parks Service] to get some oral history before the people who were there back then pass on,” he said, after a long thoughtful moment. The theme for this program was taken from Matthew 20:12. “Saying, these last have worked but one hour, and thou hast made them equal unto us, which have borne the burden and heat of the day.”

Later, as I stood at the foot of the Edmund Pettus Bridge, I thought of all the forgotten sacrifices that make justice possible.

As police cars guarded the now sacred bridge, their blue lights flashing in the chilly night illuminating Spanish moss hanging from trees near the water’s edge below, I walked across the bridge.

I walked alone. But, in spirit, thousands of others walked with me. Their sacrifices, known and unknown, allowed me to do so.

Gloria J. Browne-Marshall, an Associate Professor of Constitutional Law at John Jay College, is the author of “Race, Law, and American Society: 1607 to present” (Routledge), and the U.S. Supreme Court correspondent for AANIC (African-American News & Information Consortium).