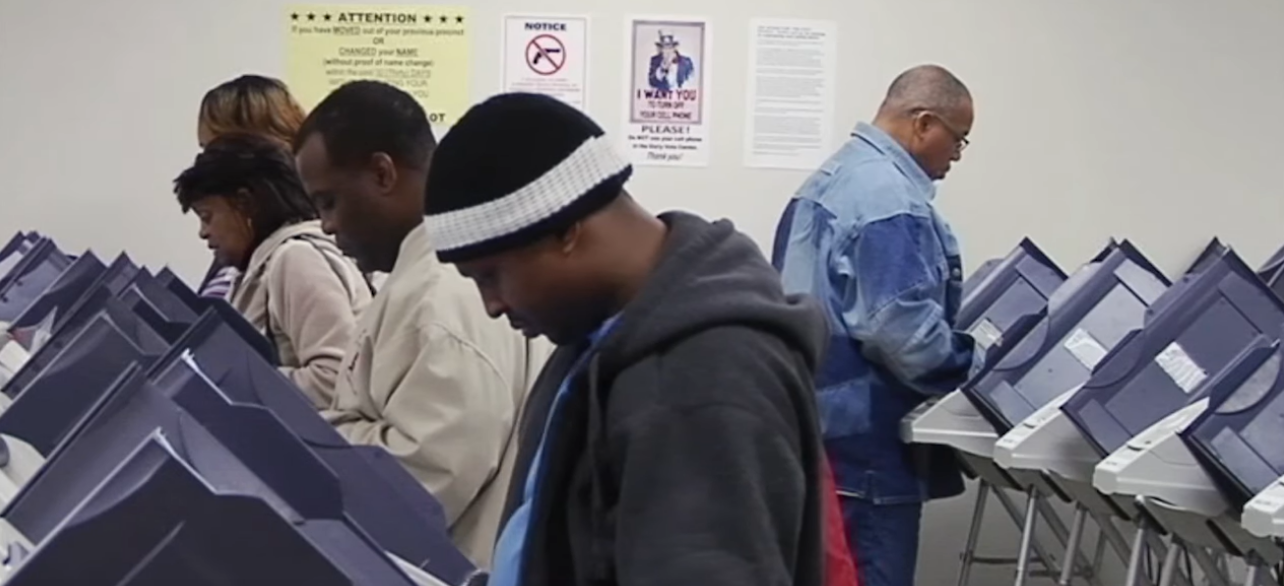

Photos: YouTube\Twitter

The U.S. Senate recently took another step toward passing transformative voting rights and election reform legislation, with Senate Democrats introducing the Freedom to Vote Act on September 14, 2021. This far-reaching reform package would take actions such as reducing the influence of money in politics, ending partisan gerrymandering, and fortifying U.S. elections against foreign interference.

But perhaps most importantly, this legislation would also set nationwide voting standards to help counteract anti-democratic laws passed by legislatures in at least 17 states. These state laws are often aimed at disadvantaging historically underrepresented communities, including communities of color, as well as lower-income voters and people with disabilities. Moreover, some of these state laws facilitate a growing threat: that partisan, conspiracy-minded election officials could sabotage legitimate election results.

For these reasons, it is imperative to expeditiously pass federal legislation to fortify free and fair elections against partisan manipulation. If Senate Republicans again block progress on comprehensive voting rights legislation, Senate Democrats must take action with a majority vote to safeguard the very foundation of American democracy—ensuring that voters, not politicians, get to decide the outcome of elections. The filibuster, an anachronistic Senate rule not conceived by the U.S. Constitution, cannot be allowed to take precedence over preserving the democratic principles on which America was founded.

This analysis highlights how specific components of the anti-democratic laws passed in four key states—Arizona, Florida, Georgia, and Texas—will create new barriers for millions of Americans to access the ballot and explains how provisions in the Freedom to Vote Act will specifically counter these laws and help prevent political interference in elections.

Background

Laws aimed at suppressing Black, Indigenous, and other people of color, as well as people with disabilities, in order to create electoral advantage for one political party over another unfortunately have a long and shameful history in the United States. Former President Donald Trump and his allies have modernized and exacerbated these efforts by spreading lies about free and fair election processes. Long before Trump lost the 2020 election, he falsely claimed that the election would be fraudulently conducted and that the result would be invalid if he lost, despite the fact that voter fraud is exceedingly rare.

Trump and his allies continued peddling their “big lie” after the election, attempting in multiple states to overturn the legitimate victory of Joe Biden. They falsely asserted that there was an array of different voting irregularities—often in predominantly Black and Latino communities—and that millions of votes should have been invalidated. Along the way, Trump tried to pressure state election officials to overturn the valid results, using a number of thoroughly discredited theories antithetical to American democracy.

Trump’s undemocratic crusade culminated in the violent January 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, where his supporters stormed the building, attempting to disrupt the constitutional counting of electors. Within hours, 147 Republican members of Congress voted to challenge the duly chosen electors in at least one state. Trump’s misconduct resulted in his second impeachment by the U.S. House of Representatives.

Despite Trump’s attempts to stop the peaceful transition of power, President Biden was duly inaugurated as president. But these events have not dampened Trump’s quest to invalidate the presidential election. Trump has encouraged sham election audits in several states. Perhaps more alarming, lawmakers across the nation have assisted Trump’s anti-democratic efforts, jamming through a plethora of laws in at least 17 states that suppress the vote and increase the risk that partisan officials will undermine the results. Many of these state laws have two related purposes: (1) to make it harder for communities of color and other historically underrepresented communities to vote, and (2) to make it easier for partisan officials to undermine valid election results with which they disagree.

In the meantime, congressional Democrats pushed for the passage of sweeping legislation to set national federal election standards, an authority granted to Congress in the U.S. Constitution. In March, House Democrats passed their comprehensive democracy legislation, the For the People Act (H.R.1). After Senate Republicans blocked any progress on the Senate’s parallel legislation, Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV) worked with several other Democratic senators to craft a somewhat more limited bill, the Freedom to Vote Act, partly in an effort to attract Senate Republicans’ support. Their efforts also incorporated feedback from state and local election officials from around the nation, to whom the legislation provides greater flexibility to implement the new provisions.

If enacted, the Freedom to Vote Act would be a giant step toward building a stronger, more inclusive democracy where all Americans can have confidence in election outcomes, even if this compromise legislation omits some important provisions from the For the People Act. President Biden voiced strong support for the legislation and reportedly is willing to ask senators to reform the filibuster in order to pass it. The Freedom to Vote Act is also widely supported by the American public.

The Freedom to Vote Act has four principal pillars:

(1) It would set national standards to protect and expand the right to vote.

(2) It would help protect the integrity of elections and make it harder for partisan officials to subvert valid election results.

(3) It would prohibit partisan gerrymandering and empower courts to invalidate overly partisan maps, an urgently needed change given that many states have already begun their 10-year redistricting process.

(4) It would reduce the power of big money in elections by, for example, shining a bright light on so-called dark money campaign spending and implementing a cutting-edge voluntary small-donor public financing system for House elections.

How the Freedom to Vote Act would help curb voter suppression and prevent election sabotage

Since the start of 2021, lawmakers across the country have filed hundreds of anti-voter bills in state legislatures. Many of these bills would curtail policies such as vote by mail, early voting, and curbside voting—secure methods that have made voting more convenient for millions of Americans. Other bills would severely restrict who is allowed to assist voters in returning their ballots and would force voters to navigate needless, onerous obstacles before they are allowed to even obtain a ballot or cast one that will be counted. Often, these anti-voting bills target Black, Indigenous, and other people of color as well as people with disabilities and members of other historically underrepresented communities.

Concurrently, the past year has seen rapid growth in legislative proposals that would increase the ability of partisan state officials to interfere with the results of elections. According to a report released in June by States United Democracy Center, Protect Democracy, and Law Forward, 41 states have already introduced 216 bills in 2021 that would allow legislators to meddle with election administration. These bills include provisions that would give partisan legislatures the final sign-off on election results, greater control over election personnel, and the ability to interfere with “the minutiae of election administration”—and would impose criminal penalties on election administrators for small missteps.

So far, only 24 of those bills have been enacted into law. But the trend is likely to continue, as more and more candidates and elected officials aligned with Donald Trump embrace the myth of a stolen election as a core issue.

The Freedom to Vote Act includes strong provisions that would protect the right to vote and counter state anti-voting efforts. Other provisions would defend free election processes and make them less vulnerable to political interference. Some of the bill’s most notable provisions include the following actions.

Bolster voter registration

- Establishes nationwide automatic voter registration (AVR) through state departments of motor vehicles with grandfathering provisions for existing AVR programs and options to expand to additional state agencies

- Creates nationwide online registration and streamlined processes

- Establishes nationwide same-day registration during early voting and on Election Day

- Establishes nationwide preregistration for 16- and 17-year-olds

- Grants voter registration privacy protections for voters who have experienced domestic or dating violence, stalking, sexual assault, or trafficking

Protect in-person voting access

- Guarantees at least 13 days of early voting, including on weekends

- Makes Election Day a legal holiday

- Grants voting protections for people with disabilities who are subject to guardianship

- Permits Indigenous tribes to designate ballot pickup and collection centers on tribal lands, which can serve as voters’ residential and mailing address for election purposes

- Tasks jurisdictions with ensuring that no voter is forced to wait more than 30 minutes to vote at polling places

- Requires jurisdictions to provide voters with timely notifications of polling place changes

- Restricts states from limiting polling place hours and bans states from prohibiting curbside voting

- Prohibits states from restricting distribution of food and beverages to voters waiting in line to vote

- Prohibits states with voter ID requirements from imposing strict limits on allowable forms of identification

Preserve mail voting

- Sets up a nationwide system of no-excuse vote by mail with ballot tracking; prepaid postage; permanent mail voting for voters choosing to receive a mail ballot each election; due process procedures for signature matching and signature curing processes; secure and accessible ballot drop boxes, including on tribal lands; and prohibitions against requiring strict forms of identification or witness and notary signatures to obtain or cast a mail ballot

- Empowers third parties such as get out the vote (GOTV) groups to distribute mail ballot applications

- Authorizes election officials to treat voter registration forms as applications for mail voting

- Funds grant programs for improving access to voter registration and voting for people with disabilities as well as pilot programs for registering and voting privately and independently from home

- Requires voting protections for U.S. citizens and uniformed service members and their families living and serving overseas

Safeguard election participation

- Expands access to and availability of voter registration and voting information, including for people with disabilities and people with limited English proficiency

- Establishes a private right of action for Americans who are denied their right to vote

- Restores voting rights to formerly incarcerated people

- Prohibits jurisdictions from using unreliable information or discriminatory methods to remove voters from voter registration rolls, such as the fact that a registrant did not vote in one or more past election

Protect elections against political interference and bolster election security

- Prohibits firing of local election officials without cause

- Enhances rules for preservation of election-related records and equipment

- Broadly prohibits undue burdens on the right to vote

- Provides grants to states for poll worker recruitment and training

- Protects against poll observers harassing voters or interfering with elections

- Requires candidates and political committees to report foreign contacts

- Requires use of voter-verified paper ballots to ensure that election results are secure and can be accurately reviewed

- Phases in a requirement that states conduct post-election audits

- Sets out requirements for counting provisional ballots

- Establishes new safeguards for the security of voting machines and data

State-by-state analysis of how the Freedom to Vote Act would counteract laws that undermine elections

The above provisions would counteract many of the worst state efforts to undermine voting rights and U.S. democracy. The four states examined below—Arizona, Florida, Georgia, and Texas—illustrate this point. These states have already adopted anti-democratic laws that, if left to stand, would block voters from casting ballots in upcoming elections and allow partisan actors to manipulate election outcomes for personal gain.

Arizona

Last spring, Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey (R) signed a series of anti-voting laws restricting access to policies that helped Arizona voters participate in the 2020 election, namely vote by mail, which about 86 percent of Arizona voters used to cast ballots in the 2020 election. The state has also made headlines for launching a partisan and conspiracy-laden investigation of Arizona’s 2020 election results, conducted by a private company whose founder made pro-Trump statements. The review ultimately—and unsurprisingly—uncovered no evidence of fraud. But it nonetheless helped fuel baseless suspicions about the results and has even led other states, including Texas, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania, to pursue similar “investigations.”

Here is what Arizona’s laws do and how the Freedom to Vote Act would remedy them:

- Arizona’s new law

In Arizona, voters who are deemed “inactive”—meaning they do not vote by mail in two consecutive election cycles and fail to respond to a mailer within 90 days—will be purged from the state’s permanent early voting list and will no longer automatically receive ballots each cycle. Opponents of the law claim that roughly 150,000 people in Arizona will be removed as a result.

The Freedom to Vote Act

The Freedom to Vote Act does not distinguish between frequent and infrequent mail voters and does not punish people for choosing not to cast their ballot by mail every election. Voters choosing to receive a mail ballot each election would remain on permanent mail voting lists unless they were no longer eligible to vote in Arizona or have submitted a written request for removal.

- Arizona’s new law

Arizona law prohibits election officials from preemptively mailing mail ballots to voters who are not on the state’s permanent early voting list unless the voter has specifically requested one.

The Freedom to Vote Act

Election officials are permitted to treat voter registration forms as mail ballot applications so that voters do not have to undertake a separate process for requesting a ballot.

- Arizona’s new law

State law now requires mail ballots to be signed and received by 7 p.m. on election night. Any mail ballot that is not signed and received by that deadline will be discarded. This will create problems for voters who return their mail ballots mistakenly unsigned in the few days preceding Election Day or on Election Day itself.

The Freedom to Vote Act

Election officials are required to notify voters within one business day if their ballot is received unsigned. The act would give voters three days following the official ballot receipt deadline to sign their ballot in order to have it counted.

- The Freedom to Vote Act

The Freedom to Vote Act would also strengthen requirements that safeguard election records—so that Arizona and other states could not hand election documents over to private contractors without supervision.

Florida

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) signed the state’s new anti-voting bill into law in May. The law was signed behind closed doors during a private pro-Trump event, which local media was barred from attending, although the governor did permit Fox News to livestream the event. Florida’s new law includes several election administration changes that will harm Floridians and undercut fair elections in the state.

Here is what Florida’s law does and how the Freedom to Vote Act would remedy it:

- Florida’s new law

The law places new restrictions on vote by mail by requiring certain voters to provide strict forms of identification to even so much as request a mail ballot. More than 4.5 million Floridians voted by mail in the 2020 election.

The Freedom to Vote Act

The bill would block Florida from requiring strict identification for requesting absentee ballots.

- Florida’s new law

Floridians used to have the option of adding their names to permanent mail voting lists and receiving a mail ballot automatically for each cycle over a four-year period. The new state law, however, forces Floridians to navigate onerous mail ballot request processes more frequently by requiring voters to request mail ballots every two years.

The Freedom to Vote Act

Voters choosing to receive a mail ballot each election would remain on permanent mail voting lists unless and until they are no longer registered in the state of Florida or have provided the state with written notice that they wish to be removed.

- Florida’s new law

Florida’s law limits drop box availability to early voting periods and to official county election offices and voting locations, curtailing their usefulness by limiting availability. About 1.5 million Floridians utilized ballot drop boxes in the 2020 election.

The Freedom to Vote Act

The Freedom to Vote Act would establish minimum standards for ballot drop boxes with requirements for at least one drop box per jurisdiction, which must be accessible during reasonable hours throughout early and regular voting periods. Drop boxes must be made available to voters as soon as a jurisdiction begins sending mail ballots to voters and must continue through the end of Election Day. Within each jurisdiction, at least 25 percent of drop boxes—or one, whichever is greater—must be accessible 24 hours daily.

Georgia

In March, Georgia enacted an expansive law that makes voting more difficult and opens the door to political interference in state elections. The nearly 100-page law drew nationwide criticism for its unconscionable voting restrictions and blatant partisan power grabs.

Here is what Georgia’s law does and how the Freedom to Vote Act would remedy it:

- Georgia’s new law

Georgia’s law prohibits people from providing food and water to voters waiting in line at polling places.

The Freedom to Vote Act

The Freedom to Vote Act would nullify this prohibition.

- Georgia’s new law

The state law bars election officials from mailing mail ballot applications to registered voters, which is an action some election officials took last year during the pandemic to ensure that people could vote even if they did not feel safe doing so in person.

The Freedom to Vote Act

The bill would allow Georgia election officials to treat voter registration forms as applications for mail ballots, thereby permitting them to proactively send mail ballots to registered voters opting to vote by mail without voters having to make a separate request.

- Georgia’s new law

Georgia’s law requires voters casting mail ballots to provide strict forms of identification to receive and return mail ballots. More than 1.3 million Georgians cast ballots by mail in the 2020 election.

The Freedom to Vote Act

The Freedom to Vote Act would block Georgia from requiring people to provide strict proof of eligibility to obtain or return a mail ballot.

- Georgia’s new law

Under Georgia’s law, jurisdictions may supply one ballot drop box for returning mail ballots. Additional drop boxes may be allowed, but the total number is limited to the lesser of one per every 100,000 active voters—that is, voters who cast a ballot in the most recent election—or the number of early voting locations in a county. This will reduce access for largely populated jurisdictions such as Fulton, Gwinnett, DeKalb, and Cobb counties.

The Freedom to Vote Act

The bill would require each jurisdiction to have at least one drop box per every 45,000 registered voters for any election held before 2024. For 2024 onward, jurisdictions would need to offer at least one drop box per every 45,000 registered voters or one box per every 15,000 voters who voted by mail in the most recent election, whichever is greater.

- Georgia’s new law

Georgia’s law requires all drop boxes to be located at official election offices and inside early voting locations, limiting their availability to hours when many voters are at school or work. Furthermore, drop boxes are only allowed during early voting periods.

The Freedom to Vote Act

The Freedom to Vote Act would supersede Georgia’s ballot drop box restrictions by requiring 24-hour access to at least one ballot drop box. It would also require drop boxes to be made available beginning on the first day that officials begin sending mail ballots through the time at which polls close on election night.

- Georgia’s new law

Georgia’s law limits weekday early voting to the hours of 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Early voting hours may be extended, but in no case can they take place outside the hours of 7 a.m. and 7 p.m. In 2020, more than 2.7 million Georgians voted early in person.

The Freedom to Vote Act

The bill would require an early voting period that is at least 13 days long, including Saturdays and Sundays. Voting locations would be required to open for at least 10 hours daily, including for some period before and after business hours.

- Georgia’s new law

Under Georgia’s law, voters who mistakenly go to the wrong precinct will be turned away instead of being offered a provisional ballot in many cases. Some 44 percent of provisional ballots cast in Georgia during the 2020 election were from people who accidentally showed up at the wrong precinct.

The Freedom to Vote Act

The bill would invalidate Georgia’s strict rules on provisional voting by allowing voters who mistakenly show up at an incorrect precinct within the county where they are registered to vote to cast a provisional ballot and have it counted.

- Georgia’s new law

Georgia’s law allows the State Election Board to investigate and replace local election officials, potentially injecting political interference into local election administration.

The Freedom to Vote Act

The Freedom to Vote Act would prohibit the removal of local election officials except for “gross negligence, neglect of duty, or malfeasance in office.”

- The Freedom to Vote Act

The bill would also make it illegal to “intimidate, threaten, [or] coerce” election officials—a protection against the type of pressure that was put on Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger to change the results of the last presidential election.

Texas

In September 2021, despite a hard-fought, monthslong effort by many Democratic state lawmakers seeking to block it from advancing, Texas became the latest state to adopt a sweeping anti-voting law that also gave unprecedented power to partisan poll watchers.

Here is what Texas’ law does and how the Freedom to Vote Act would remedy it:

- Texas’ new law

Texas already has one of the most restrictive mail voting programs in the country, limiting access to only a limited class of people, namely elderly people; people detained in jail or located outside the jurisdiction during the election; and certain people who are ill or have disabilities. Still, for those limited few who are eligible for mail ballots, the state’s new law requires them to provide strict forms of identification to receive or return their ballot. Almost 1 million Texans voted by mail in the 2020 election.

The Freedom to Vote Act

The bill would allow any voter to cast a ballot by mail and would block Texas from requiring mail voters to provide strict identification to obtain or return a mail ballot.

- Texas’ new law

Texas’ law makes it a felony for election officials to preemptively send mail ballot applications to registered voters. Some Texas counties tried to preemptively send mail ballot applications to elderly voters and voters with disabilities during the pandemic and when postal delays risked ballot request forms not being received on time. The state law similarly blocks officials from facilitating ballot application distribution by third-party groups, such as GOTV groups.

The Freedom to Vote Act

The Freedom to Vote Act would empower election officials to treat voter registration forms as mail ballot applications, thereby allowing them to proactively send mail ballots to voters opting to vote by mail without voters having to navigate a separate ballot application process. The bill would further allow distribution of mail voting applications by third parties.

- Texas’ new law

The new state law prohibits ballot drop boxes. Of voters nationwide who cast ballots by mail, 41 percent reported utilizing ballot drop boxes to return their ballot.

The Freedom to Vote Act

The bill would negate the state’s ballot drop box ban by requiring each jurisdiction to have at least one drop box per every 45,000 registered voters in elections occurring before 2024 and the greater of that or one box per every 15,000 voters who voted by mail in the most recent election from 2024 onward.

- Texas’ new law

Texas’ law bans curbside voting. Curbside voting was greatly relied upon in heavily populated Harris County. Curbside voting proved vital for protecting voters during the pandemic by enabling them to cast an in-person ballot without leaving their car or having to enter a crowded polling location. In Harris County, 1 in 10 in-person early voters utilized curbside voting.

The Freedom to Vote Act

The bill would bar states from banning curbside voting.

- Texas’ new law

Texas’ law allows poll watchers to have “free movement” in a polling place—potentially disrupting the voting process or violating voters’ privacy—and even goes so far as to criminalize the obstruction of a poll watcher’s view.

The Freedom to Vote Act

The bill would require election observers to stay at least 8 feet away from a voter trying to cast a ballot or from poll workers trying to process ballots. Furthermore, it would prohibit observers from challenging anyone’s eligibility to vote without personal knowledge of the grounds for ineligibility and a good faith factual basis to believe they are ineligible.

Conclusion

America’s dream of an inclusive and fair democracy stands at a pivotal point. The Freedom to Vote Act is likely Congress’ best chance to enact critical legislation to protect voting rights and election integrity as well as prevent partisan gerrymandering and reduce the outsize role of big money in politics. With multiple states enacting laws that strike at the heart of voter access and election integrity, the Senate must fulfill its constitutional duty and act expeditiously to pass the Freedom to Vote Act.

Danielle Root is the director of voting rights and access to justice on the Democracy and Government Reform team at the Center for American Progress. Michael Sozan, a former chief of staff in the U.S. Senate, is a senior fellow at the Center. Alex Tausanovitch is the director of campaign finance and electoral reform on the Democracy and Government Reform team at the Center.