Photos: YouTube

A major article by climate writer David Wallace-Wells in the New York Times in late October, published just before the start of the United Nations COP 27 climate conference in Egypt, made the case that, in reference to efforts to solve the climate crisis and as summarized at the end of the article by Canadian atmospheric scientist Katharine Hayhoe, “We’ve come a long way, and we’ve still got a long way to go. We’re halfway there. So take a breather, pat yourself on the back, but then look up—that’s where we have to go. So let’s keep on going.”

In all honesty, this was not the viewpoint of a number of the people Wallace-Wells interviewed for this article. Others, and Wallace-Wells himself sometimes, said things like:

-“We have squandered the opportunity to limit warming to ‘safe’ levels.” (Wallace-Wells)

-“Each time you get an IPCC report, it’s still worse than you thought, even though you thought it was very bad.” (Nicholas Stern)

“The danger is that you have a world that runs on sun and wind but is still an essentially broken planet.” (Bill McKibben)

“What we are witnessing at the present level of warming is already challenging the limits of adaptation for humans.” (Fahad Saeed)

Why do Kayhoe, others quoted by Wallace-Wells and WW himself have this “glass half full” point of view?

Some of it could be tactical. As long as I’ve been in the climate movement there has been discussion about the need to give people some hope that we can change our very desperate situation, not be all doom and gloom. Most people on a personal level want to operate from a place of hope and not despair. But there are valid reasons for believing that we could be turning the corner on this existential battle for the future.

A lot of it has to do with the unexpected acceleration of the shift away from coal, combined with the rapid growth, and rapidly decreased cost, of wind and solar energy. “A report by Carbon Tracker found that 90% of the global population lives in places where new renewable power would be cheaper than new dirty power.”

Another big reason is that, this year, “investment in green energy surpassed that in fossil fuels, despite the scramble for gas and the ‘return to coal’ prompted by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.” Without a doubt, the still-growing, international, fossil fuel divestment movement had something to do with this.

Less significant, if of note, is that “90% of the world’s GDP is governed by net-zero pledges of various kinds, each promising thorough decarbonization,” although “at this point, they are mostly paper pledges.” (Wallace-Wells)

Along these lines, a few days ago writer Hunter Cutting reported: “A conservative summary of all the new data finds that total methane emissions from U.S. oil and gas operations are at least twice the U.S. EPA count and twice what the U.S. reports to the UNFCCC under the terms of the Paris Climate Agreement. This under count has been affirmed by the U.S. National Academies. A recent U.S. Congressional investigation into the under count found that the EPA counts are even lower than the estimates found in the internal records of the oil and gas industry.”

Why is this happening at the EPA? It’s because the fossil fuel industry dominates US political and regulatory institutions. That’s why, in the face of all we’ve known for decades about the climate crisis, dirty methane gas, not renewables (yet), has replaced coal as the main energy source for electricity in the US.

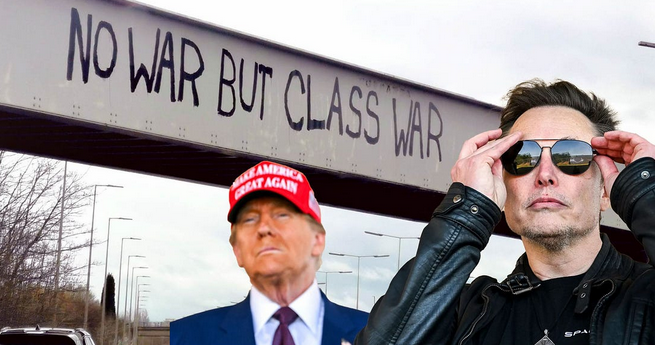

Indeed, it’s really all about the power of the 1% vs. the rest of us and the world’s disrupted ecosystems. When the richest 1% worldwide hold more than 70% of the world’s wealth, as reported by Oxfam, and the fossil fuelers are all over that 1%, that’s the major impediment to progress on climate as well as a whole range of issues. People who get it on the seriousness of the crisis but who are in positions of power and influence within government and media consciously or semi-consciously pull their punches, don’t speak or write the whole truth, because of the damage the powers-that-be could do to their careers.

Unfortunately, Wallace-Well’s piece makes no mention of these basics facts about who has wielded the ultimate decision-making power, and who still does, as evidenced by the fact that the number of delegates from the fossil fuel industry was larger at COP 27 than any of the previous 26 of them. Shame on the organizers for allowing that to happen!.

An important new book on the climate crisis, Nomad Century, by scientist and writer Gaia Vince, reflects a similar weakness, if somewhat mitigated.

Nomad Century is a valuable book. Bill McKibben calls it “an important and provocative start to a crucial conversation.” In it Vince forthrightly looks at how the world is likely to change if there is no major and immediate course correction by the world’s governments. For her, that means a possible increase of 3-4 degrees Centigrade compared to pre-Industrial Revolution levels. Right now the UN goals are between 1.5 and 2 degrees, but what has been pledged so far would get us closer to 3 degrees, and pledges are just that, by no means certain.

As the title of her book indicates, Vince sees massive migration as central to what the evolution of the climate emergency will mean for the world: “When looking at the future the baseline shouldn’t be thought of as your current life as lived today—the comparison rather is between your future city embroiled in climate-adaptive infrastructure changes, a hotter environment with flash floods, more violent storms, poor food availability, a shrunken workforce with little elderly care, a social environment of fear with increased conflict, terrorism, famine and death broadcast to your screens from the global south. . . or far less of the misery, but many more foreign people living in denser cities.” (p. 94)

She projects that the countries in the northern latitudes— Canada, Scandinavia, Russia, also Alaska—as where many migrants will move to over the course of the century because the climate in or near those latitudes will become the most hospitable to human habitation. There will be the emergence of mega cities that dwarf what exists today because there will be less land available to grow food. Migration within countries and across borders will become much more common for many more people, and there will have to be internationally-connected efforts to enable it to happen in a less destructive, more organized way.

There is much more in her book as far as ways that the world will have to change, much of it of value, some of it definitely provocative. Climate author Kim Stanley Robinson describes it as “cognitive mapping to understand the situation and see a way forward.”

However, in a way similar to Wallace-Wells, there is an essential acceptance of the dominance of the “wealthy elite,” as she herself names them. This is the case even though occasionally her writing indicates that she understands the deeply unjust nature of the world order: “It’s clear that there is tremendous inequality within and between countries, with nearly 3,000 billionaires at the same time as the majority of the world’s people live on very low incomes without access to even basic products. . . This pathological accumulation of wealth could be far better used by society.” (pps. 181-182)

The closest she comes to calling for the system change that is essential if we are to have a chance of forestalling a much worse future than the present is when she writes toward the end of the book, “Everything we need and more can be made from the body of the earth and its biology. It is through our invented human socioeconomic system [Glick paraphrase: corporate capitalism] that we limit ourselves. We can innovate ourselves out of that limitation too, if we choose, but it is far harder to do. We may find we have no choice.” (p. 187)

Another weakness common to both authors is an almost total absence of even the words, much less analysis, of the climate tipping points the world is facing. I couldn’t find those two words anywhere in “Nomad,” and it was in Wallace-Wells’ piece only once, in a paragraph about British economist Nicholas Stern’s views on the crisis: “He worries about the future of the Amazon, the melting of carbon-rich permafrost in the northern latitudes and the instability of the ice sheets—each a tipping point that ‘could start running away from us.’”

So of what importance are the US election results to all of this?

Without question, a Republican “red wave” would have been disastrous, not just because of what would happen on Capitol Hill but because it would have demoralized those who oppose and energized those who support Trump and the extreme right. Because the election was essentially an unexpected draw between the Dems and Reps, there is hope for the future, on climate and many other issues.

It is a very big deal that the Democrats have retained control of the Senate and that the climate denying Republicans will have a much smaller majority in the House of Representatives than the media pundits were predicting.

It also looks as if the Congressional Progressive Caucus in the House will gain additional members. That is a good thing. This is the broadly-based entity—about 100 members– which has been giving leadership for action much more at the scale of the problem when it comes to climate and other issues. The CPC “advocates for progressive policies that prioritize working Americans over corporate interests, calling for bold and sweeping solutions to the urgent crises facing this nation [including] taking swift action to stop the warming of our planet.”

The turnout percentages overall for women, people of color and young people were decisive in beating back the “red wave.” These are the constituencies, in addition to some segments of organized labor, which are most consistently in support of action on climate as well as on a range of other survival, justice and care issues. It was the broad support of the Green New Deal by these constituencies that led to the Inflation Reduction Act, much weaker than it would have been if Manchin and Sinema were not Senators but still an important step in the right direction on climate, tax reform and health care.

Finally, it is very significant that there were a number of somewhat connected organizations doing critical, on the ground, voter education and turnout work, groups which operated independent of the Democratic Party. This was a major factor in Trump’s defeat in 2020, and in 2022 it was probably even more decisive. In non-election times these groups do the essential day-after-day organizing and demonstrative actions around the issues of working people of all genders, cultures, ages, and nationalities. They break down white and male supremacy and heterosexism as they organize around issues of importance to many, like racial justice, health care, the schools, abortion rights and environmental protection. That kind of work will continue and needs to be broadened and strengthened.

The conscious recognition of the reality of this multi-tactical, multi-issue “third force”—not a “third party”—and its increased interconnection and coherence going into 2024 and beyond is an absolute essential if we are to break the current 50/50 national split between the center/left forces and the right/extreme rightist forces. We need a unified, organized, mass people’s movement which can impact the US body politic in ways that will never come to pass via the Democratic Party as presently constituted.

We’re still here, we’re still standing, we’re still fighting, and there’s still realistic hope that we can defeat the Trumpists and make this the decade of major social and political transformation that it can be, that it has to be.

Ted Glick is an organizer with Beyond Extreme Energy, President of 350NJ-Rockland and author of the recently published books, Burglar for Peace and 21st Century Revolution. More info can be found at https://tedglick.com, and he can be followed on Twitter at https://twitter.com/jtglick .