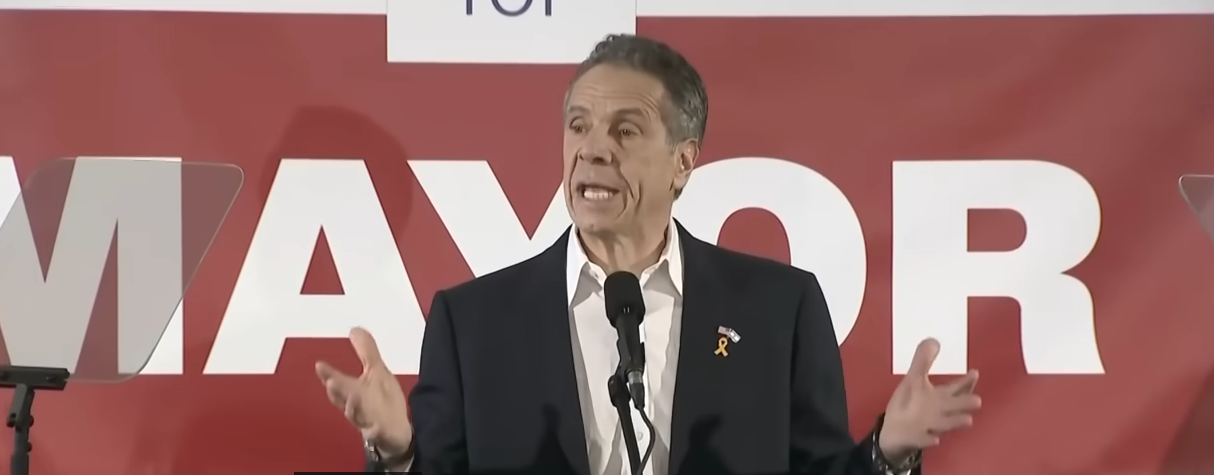

Photos: YouTube

Last summer, people across the country took to the streets to protest police violence and, led by Black Lives Matter, took part in one of the largest movements in American history.

With New Yorkers from Buffalo to Long Island – in small towns and large cities – demanding change, state lawmakers knew they had to do something.

In response, legislators passed a slate of important police reforms, including the repeal of civil rights law 50-a, which was used by police departments for decades to hide officer disciplinary records from the public. For years advocates pushed for 50-a to be scrapped and finally, under immense pressure, lawmakers acted.

When 50-a was repealed a year ago today, the NYCLU and other police accountability advocates understood that this was just a start, and that much more had to be done to transform policing. And yet, even this one step has been attacked, impeded, and undermined by police departments across the state.

Since 50-a was repealed, the NYCLU has sent 13 Freedom of Information Law requests to law enforcement agencies across the state to review previously hidden police disciplinary records. These records provide a window into how often police are accused of harming New Yorkers, and what punishment – if any – they receive when they are caught.

The repeal of 50-a was supposed to mean that, at long last, this information would be available to the public. But many law enforcement agencies rebuffed our efforts. After nine months, all 13 departments have failed to turn over all the information we requested. We’ve already sued seven police departments across the state, with more litigation in the works.

Despite continued efforts to keep police misconduct a secret, getting rid of 50-a has led to important victories for transparency. The NYCLU published a database of nearly 280,000 complaints to the Civilian Complaint Review Board about NYPD misconduct. This unprecedented disclosure led to revelations about some of the most abusive officers, including high-ranking members, and provided clear evidence that the NYPD rarely hands out serious discipline, even when there is evidence of serious violence and abuse.

These types of disclosures would not have been possible with 50-a on the books. But the continued, ferocious pushback from departments and police unions to even this basic step towards transparency is indicative of the immense power they have.

Another example of this dynamic is the fight to bring civilian oversight to police departments across the state. Communities in Long Island, Rochester, Syracuse, and Poughkeepsie have been advocating for strong civilian oversight boards for their police departments. And at every turn, they meet fierce resistance.

That’s one reason why we must go further than simply reforming law enforcement. Small victories are not easily won because police departments use their enormous power to fight tooth and nail to hold on to it and to maintain the status quo. To reduce law enforcement power, we must cut police budgets and reinvest that money in things like better schools, jobs, housing, health care, and infrastructure.

We also cannot let police departments’ power deter us from continuing our struggle. Everyday people can join the fight. New Yorkers have the right to request disciplinary records from their local police department by submitting a FOIL request. They can also let their local lawmakers know where they stand and demand that they hold police departments – who ultimately should answer to the public – accountable.

We won’t be able to achieve transformative change without defunding law enforcement. And we won’t be able to do that without more marches, rallies, and other forms of protest and activism that put pressure on people in power to act.

Written by ACLU’s Shannon Wong and Simon McCormack