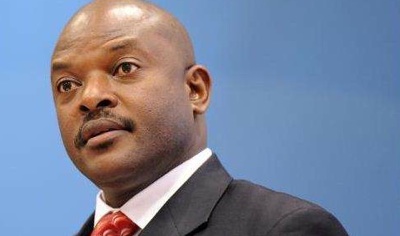

President Nkurunziza — challenges remain

The Burundi conflict escalated on May 13 with these words by Maj. Gen. Godefroid Niyombare on May 13th, in Bujumbura, the capital of Burundi: “President Pierre Nkurunziza is removed from office.”

This ominous announcement came in the wake of relentless protests by people opposed to President Nkurunziza’s determination to run for a third five year term in contradiction of a constitutionally mandated two five-year term limit.

Twenty-five people or more were killed during the civil unrest. The response to the apparent coup announcement was swift. Thousands of people poured out onto the streets of Bujumbura to celebrate the apparent victory by demonstrators. Condemnation of the coup from many quarters was equally swift. This included the East African leaders who were meeting in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania, to plot how to resolve the then-unfolding crisis in Burundi.

Others who condemned it included the African Union, the United Nations, the United States, other countries and individuals even though it was still unclear if the coup was successful.

To add to the uncertainty, President Nkurunziza issued a statement claiming that the coup had not succeeded. Continued gunshots in the capital also signaled that the contest for the control of the government was not yet settled. Consequently, the celebratory mood quickly subsided. By the end of the day on Thursday May 14, it became clear that the coup attempt had failed.

While government change by military coup is generally undesirable, it is quite wrong to simply condemn a coup without examining the context in which it occurs. In the case of Burundi, the coup attempt did not occur spontaneously but as a culmination of a long process.

The Burundi case was comparable to Burkina Faso’s where Blaise Compaore tried to extend his rule with an attempt to manipulate the constitution. Demonstrators burned down the Parliament to prevent such a move and drove him out of the country. They threatened protests when the army tried to hijack the revolution. A transitional government was created and elections are due this year.

In Burundi, for months, if not longer, the public had been calling for the implementation of the constitutionally mandated two-five year presidential term limit. Article 96 of the 2005 Constitution states that the head of state will be elected for a mandate of 5 years renewable one time. President Nkurunziza is in the second term as President, the first having been elected by members of parliament while the second one came by a direct election.

Unfortunately, article 96 is ambiguous on whether the term limit includes election by parliament or not. President Nkurunziza argues that the term limit applies only to direct election by voters whereas the opposition thinks it should include presidential election by parliament as well. Ordinarily, the judiciary should be the one to resolve the contradictory interpretation. The constitutional court under duress ruled in favor of the president.

So, why did the people not accept the court ruling? While the court may seem to be technically right in its ruling, President Nkurunziza and the court forgot that it is the people who are the ultimate arbitrators. After all, members of parliament who unanimously elected Nkurunziza president in August 2005 acted in good faith on behalf of the people who elected them. By accepting his election more than six months after the adoption of the constitution, he must have assumed that the election by members of parliament was consistent with the newly-adopted constitution and that he was serving his first term.

Some people argue that even if President Nkurunziza were to contest for the third term, the people would have an opportunity to vote him out. This argument assumes that the election would be free and fair. Unfortunately, elections in many developing countries are often not free and fair due to rigging by incumbents, vote buying, intimidation and other types of fraudulent conduct.

Even the judiciary which is supposed to be neutral often sides with those who cling to power. Consequently, people have no faith in elections organized and managed by dictators.

The call for the East African leaders to resolve the crisis is not encouraging. Other than the President of Tanzania, the others all owe their ascension to or stay in power to some extent to Uganda’s Gen. Yoweri Museveni:Uhuru Kenyatta of Kenya, Gen. Paul Kagame of Rwanda and Gen. Salva Kiir of South Sudan.

Without President Museveni’s vigorous condemnation of the International Criminal Court (ICC) and campaign to delegitimize it in Africa, President Uhuru might not have survived his indictment for his role in the horrific 2007 post-election violence in Kenya.

Without Ugandan troops now fighting in the South Sudan, President Kiir would not survive. Kagame is Museveni’s protégé. Presidents Nkurunziza and Uhuru are President Museveni’s comrades in arms battling Al-Shabaab in Somalia.

It is, therefore, unlikely that they could constitute a neutral arbitrator in the Burundi conflict. Tanzania would be out numbered 3 to 1 even if it were to side with the demonstrators for term limit in Burundi.

In any case, President Museveni, in particular, should recuse himself from arbitrating matters of term-limit because he has been clinging to power for nearly 30 years. To him, President Nkurunziza’s insistence on running for a third term is a normal small burden to impose on the people of Burundi.

In Uganda, he wasted no time in clamping down on the opposition just in case they take a leaf from their Burundian neighbors. He arrested opposition leaders last Thursday for no good reason other than that they were going to meet to discuss electoral reform, including an independent election commission not appointed by and loyal to Gen. Museveni. Uganda votes in March 2016.

Outside the continent, the U.S. and European countries such as Britain are close allies of Gen. Museveni.

Presidents Museveni, Nkurunziza and Uhuru are all fighting a proxy war on behalf of the U.S. in Somalia; they have stationed thousands of troops to battle Al-Shabaab. That makes it unlikely that this axis of power can be a neutral arbitrator in the struggle between the people and President Nkurunziza. In fact just this past Sunday Nkurunziza declared that there may be a threat to Burundians from Al-Shabaab. He is using the same scare-mongering tactics Museveni has used for years to ingratiate himself to the U.S. and U.K.

The U.S. in particular and other countries, organizations and individuals who condemned the attempted coup in Burundi failed to recognize that this is the same wind of change that swept across North Africa and caused the demise of long-term rulers like Gen. Hosni Mubarak that’s now finally making its impact in Africa south of the Sahara.

Even though Nkurunziza held on, the problems persist and the people’s demands won’t disappear.

Other leaders in the region, including Gen. Museveni himself, Nkurunziza’s chief patron, are feeling the breeze which can turn out into full-blown winds.