Photos: EJI

Thousands of people are learning about the work of EJI and the issues we address through three riveting memoirs published this year. EJI is proud to add these highly acclaimed books to its library of works that advance an understanding of our history of racial injustice and its legacy that we believe is necessary to meaningfully address contemporary issues like over-incarceration and police violence.

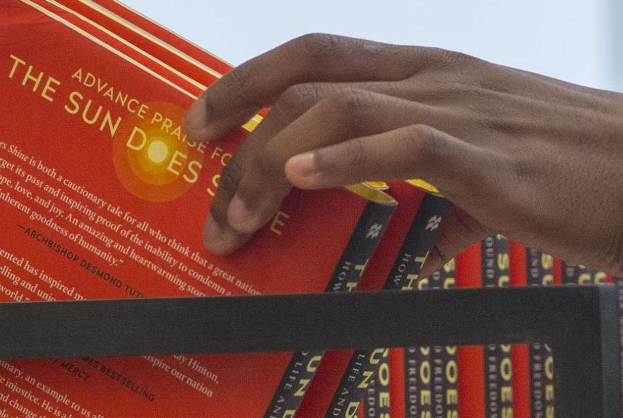

Like Anthony Ray Hinton’s bestselling memoir, The Sun Does Shine, and Just Mercy, the award-winning book by Bryan Stevenson that was recently adapted into an award-winning feature film, these books tell powerful stories about the work of EJI, the people we represent, and the importance of confronting injustice.

My Time Will Come: A Memoir of Crime, Punishment, Hope, and Redemption

At age 13, Ian Manuel was arrested and charged with a non-homicide offense that resulted in him being sentenced to die in a Florida prison.

EJI took on his case and argued that it is cruel and unusual punishment to sentence a 13-year-old child to life imprisonment with no chance for parole. EJI won Mr. Manuel’s release in 2016.

In May, Mr. Manuel released a powerful memoir documenting his struggle from childhood in Tampa’s most violent and abusive housing projects, through 18 years of solitary confinement, to freedom.

My Time Will Come: A Memoir of Crime, Punishment, Hope, and Redemption tells of the abuse, neglect, and violence Ian suffered from infancy up to the moment in 1990 when 13-year-old Ian was directed by older juveniles to commit a robbery.

During interviews and events to promote the book, Mr. Manuel advocated for ending solitary confinement for children.

“I witnessed too many people lose their minds while isolated,” Mr. Manuel wrote. Just as he used his imagination to survive 18 years in isolation, he’s now determined to use his writing to make sure no other child has to endure what he did.

“No human being should have to live through what I lived through.”

Waste: One Woman’s Fight Against America’s Dirty Secret

Catherine Coleman Flowers, a longtime community advocate with EJI and MacArthur Genius Award winner, wrote one of the Ten Best Science Books of the year—“a gripping, eye-opening story about the lack of access to basic sanitation in parts of the United States.”

Her memoir, Waste: One Woman’s Fight Against America’s Dirty Secret, tells the story of her journey from growing up in Lowndes County, Alabama, to becoming a student civil rights organizer and then emerging as a champion of the modern movement for environmental justice.

Ms. Coleman Flowers’s “powerful and moving book” has exposed the world to the racial disparities in wastewater treatment in Alabama’s Black Belt, where over half of homes have inadequate sanitation services and children are not allowed to play outside due the risk of exposure to raw sewage.

“I never imagined that a book about raw sewage would be a real page-turner but Catherine Flowers’s Waste is just that. When the United Nations considers access to sanitation a basic human right, it is shocking that in this wealthiest of nations the most challenged and forgotten people continue to be flushed and forgotten. This book is a stunning eye-opener.” —Jane Fonda, actor, activist, and author

Chasing Me to My Grave: An Artist’s Memoir of the Jim Crow South

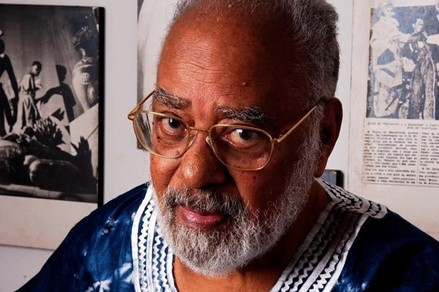

This memoir by Winfred Rembert, one of the nation’s most courageous and extraordinary artists, was released shortly after Mr. Rembert passed away in April. EJI director Bryan Stevenson, who wrote the foreword, called it “a compelling and important history that this nation desperately needs to hear.”

Named a Best Book of the Year by NPR, Publishers Weekly, Booklist, BookPage, Barnes & Noble, and Hudson Booksellers, Chasing Me to My Grave was celebrated on the Carnegie Medal of Excellence in Nonfiction Longlist and is an African American Literary Book Club #1 Nonfiction Bestseller, among other accolades.

The book presents Mr. Rembert’s extraordinary body of work alongside the story of his life growing up in a family of Georgia field laborers. When he was a teenager, Mr. Rembert was nearly lynched by law enforcement who arrested him after he participated in a civil rights demonstration. He spent the next seven years working on prison chain gangs.

At age 51, he began to use leather to create vividly detailed pictures of his near-lynching and his time working on the chain gang. He had learned leather-working in prison, and his vibrantly colored, painstakingly carved pieces portrayed joyful and painful scenes from his life in rural Georgia.

Mr. Rembert’s work has been exhibited at museums and galleries nationwide and was the subject of an exhibition at the Yale University Art Gallery. Among other accolades, he was awarded a United States Artists Barr Fellowship in 2016.