By Dr. Brooks Robinson\Black Economics.org

Photos: YouTube Screenshots\Wikimedia Commons

Logically, and it should not be surprising, our late November 2024 release of an analysis brief on “group economics” revealed that Black Americans practiced the just-mentioned concept by spending a mere estimated 13.1% of our total “spending power” with Black American

entrepreneurs during 2020.[i]

The current splintering and fragmenting of the US along political lines is also mirrored along racial

lines. Given the current high level of uncertainty and prospects for its continued intensity and long

duration makes the following statement appear as a wise choice: Black Americans should prepare

for a renewed surge of fighting in the undeclared, but over 400 year-long war in the US.

We are not referring here so much to violent conflict; although that is certainly included. Rather,

concern is focused on socioeconomic and political conflicts.

Economically, we can do no better than ensure the functional/operational existence and practice

of Kujichagulia and Ujamaa, self-determination and cooperative economics, respectively, in our

“areas of influence” (communities).[ii]

Even before this preferred condition materializes, and to ensure it is sustained and expanded, it is

important to “name it and claim it.”[iii] Such a positive affirmation and agreement on Black

Americans’ practical goals and aspirations is essential for our success—knowing all the while that

we are more than prepared to work and produce our desired outcomes.

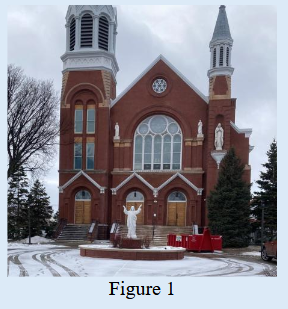

Before elaborating on “naming it and claiming it,” it is appropriate to highlight two related experiences. First, we note our current research study effort in Fargo, North Dakota and turn your attention to Figure 1. It shows St. Mary’s Cathedral, which stands on Broadway Street. A white sculpture of Jesus inviting all to the “kingdom” is positioned conspicuously at the front of the cathedral. Although situated at a northern latitude with a cold climate, this sculpture reflects no modification to Jesus’s “standard” attire: A flowing robe made of a thin fabric. As a result, the sculpture is even more striking to those

passing by, who are not fully adjusted to winter. Those observing the cathedral and the Jesus sculpture are motivated to inculcate the following obvious, but subtle 2 (subliminal) messages: (1) Jesus is White, which means that God is White; (2) Jesus and Whites can address any issue or concern, undeterred by inclement weather; (3) Jesus and his Whiteness are linked directly to light (even divine knowledge) and rightness.[iv] This tripart thought (and it need not be limited to three) is at the root of White Supremacy which is packaged well in a message that was, and continues to be, taken the world over to expand, reinforce, and sustain Whites’ positions at the top of the socioeconomic hierarchy around the globe.[v]

The just-mentioned messages have produced egregious harm to the world’s Black population,

which should issue a powerful response. Black people of the world must counteract, unseat, and

reverse this White Supremacy program if we are to rise. A starting-point and crucial realization is

that wherever the Christian message has been, or is being, taken, White proselytizers have named

and claimed as much in sight as possible.

Second and conversely, during our limited travel and working time on the African Continent, we

were perplexed concerning Africans’ failure to conduct widespread renaming of aspects of their

world that were reclaimed from colonizers. Our personal consternation about this was amplified

by time spent in South Asia. Unlike Africans, South Asians have been enthusiastic about

reinstating the full scope of their culture since their 1947 break with the British. Not everything,

but almost all important aspects of the South Asian world have undergone renaming and

reclaiming to undo the British former powerful presence. With or without financial and other

resources, South Asians have charged ahead to recapture control of their world and remove

vestiges of White Supremacy so that its impact is diminished. On the other hand, when enquired

of Africans why they have not made similar efforts to preserve their heritage and thwart negative

fallout from White Supremacy programs, the responses received mainly highlighted a fear of

losing tourism receipts.

These are external “naming it and claiming it” experiences. What about the Black American

experience? After Black Americans enjoyed solidarity in achieving a National MLK Holiday,

many thoroughfares all over the nation are labeled “MLK.” Certain local authorities have gone so

far as to relabel some of their most important thoroughfares “MLK,” irrespective of whether they

are located in or around pockets of Black American populations.

Black Americans, who seek to increase and improve our practice of Kujichagulia and Ujamaa,

can do so by “naming it and claiming it.” Specifically, where we have enclaves of significant sizes,

with or without approval of local authorities, we can unilaterally relabel schools, streets, parks,

etc. that are located within our enclaves and for our own satisfaction. It is by giving more

significance to where we live and claiming more “ownership” of it that we can motivate and

stimulate internal energy to intensify and expand our efforts to achieve that favored state where

we exercise control over our areas of influence, economically, socially, politically, and otherwise.

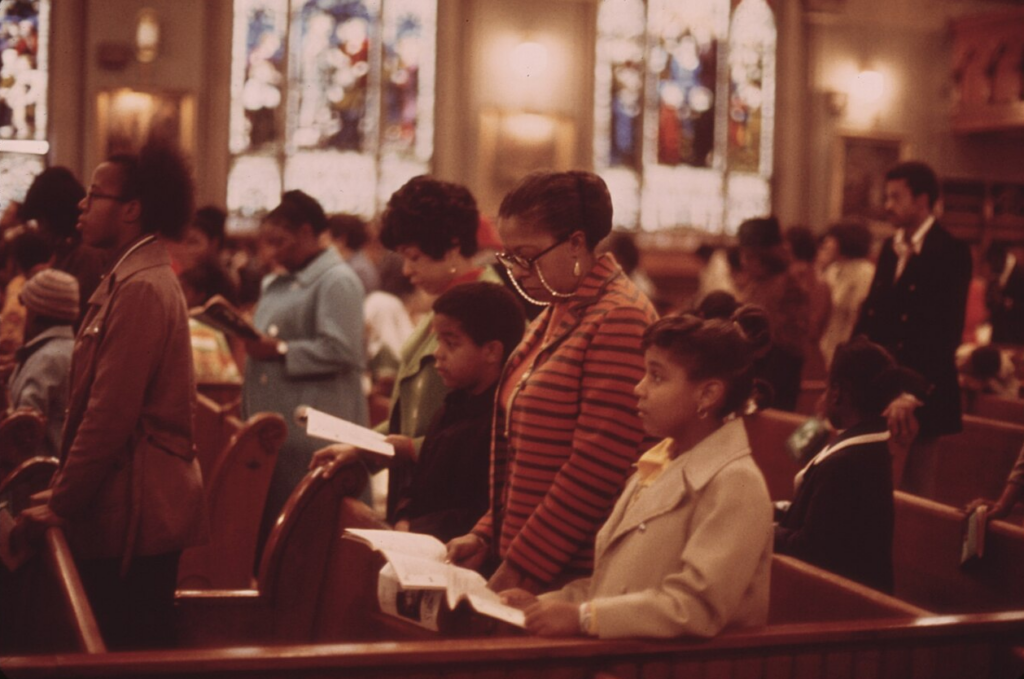

As we walk through our enclaves on Sunday mornings, we hear joyful noise emanating from our

places of worship (especially those of Pentecostal or Evangelical faiths) in the form of a question

and a related cry: “Do you have a need, a requirement? Then name it and claim it!” We should all

begin to take this gospel—adding elbow grease in the form of work—from the sanctuary to the

streets in our communities so that we seize greater control of our lives and elevate our overall

socioeconomic wellbeing.

Dr. Brooks Robinson is the founder of the Black Economics.org website.

References:

[i] Brooks Robinson (2024). “‘Group Economics’ for Black Americans (Afrodescendants).” BlackEconomics.org; https://www.blackeconomics.org/BELit/gefbaa112924.pdf (Ret. 121924).

[ii] Kujichagulia and Ujamaa are Kei Swahili terms that account for two of the Seven Kwanzaa Principles (Nguzo Saba). Kwanzaa is a seven-day international holiday and celebration enjoyed mainly by African and Afrodescendant People around the globe; https:/ www.officialkwanzaawebsite.org/ (Ret. 121924).

[iii] It is believed (according to Generative AI) that Frederick J. Eikerenkoetter, II (June 1, 1935 – July 28, 2009) aka Rev. Ike was the first to popularize the phrase “name it and claim it.” Rev. Ike was a prosperity gospel preacher headquartered in New York City.

[iv] We discussed the near ubiquitous association of Whiteness with rightness, righteousness, goodness, and divinity in Chapter One of Brooks Robinson (2007), Black Americans and the Media: An Economic Perspective. Unpublished. See footnote 2 on page 1. https://www.blackeconomics.org/BEMedia/chapterone.pdf (Ret. 121924). When the white

color issue surfaces, often the types of connotations noted in the text of this essay are presented; and in certain cases, mirror connotations are provided for the color black. Seldom will one find a rebuff of the white connotations. We provide such rebuffs. The color white, which is not identical to a “clear” or translucent color,” is associated, inter alia, with the following non-exhaustive outcomes as viewed in our natural environment. We start with the

overarching significance of white. In our view, it serves as a “warning;” including being at a pinnacle with nowhere to go but downward: viz., white snow signals the onset of winter (coldness, dormancy, morbidness, and death); and a snow-peaked mountain top is a pinnacle with only a downward direction. Is a global economy dominated by Whites a warning that we have reached a pinnacle that will be followed by a precipitous decline? A property of the

color white is as a reflector of light. It is interesting that many (wood and stone) churches are painted white; presumably with the expectation, at least in part, that white reflects/deflects—not attract or absorb—evil (the presumed dark). White ocean foam warns of a forceful tide; a frothy white condition is too hot; white-hot iron or other metal implies pliability—something not typically desired in metals; a shallow cut of black or brown skin will reveal whiteness, warning that the next level is bloody. An important connotation of the color white is that

something is lacking/missing/absent: viz., albinos, who are without pigment; and blank white pages that scream for colored ink. White automobiles typically cost less than automobiles painted with non-white colors. The foregoing examples reveal that the color white is tightly linked to connotations that are not so noble, right, righteous, good, favorable.

[v] We discuss this topic in more detail in the chapter, “Jesus the Salesman” in Brooks Robinson (2024), Merida Musing, BlackEconomics.org, pp. 32-36; https:/ www.blackeconomics.org/BEAP/memu041924.pdf (Ret.

121924).