Photos: YouTube Screenshot\Album Covers\Ras Kefim

By Ras Kefim

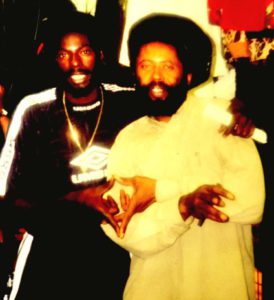

In the following article, by New York-based author and businessman Ras Kefim, he talks about his chance meeting with Reggae artist Buju Banton, in Queens, New York near his business location. Ras Kefim is the author of the recently released book Deception In the Name Of the Lord. Read more about Deception In the Name Of the Lord in this Black Star News article. Kefim is shown in the photo below (on the right) with Buju Banton.

Buju Banton, born Mark Anthony Myrie, is a popular Jamaican Reggae\Dancehall musician. He is one of the most prolific and well-regarded artists in Jamaican music and in the international music scene.

The name Buju was given to him as a child by his mother.

Banton was born on 15, July 1973 in Kingston, Jamaica, in a poor neighborhood known as Salt Lane. His father worked as a laborer at a tile factory, while his mother worked as a street vendor.

The word “Banton” means someone who is a respected storyteller. But it is also the name of a DJ Buju admired, Burro Banton, an earlier giant in the Dancehall fraternity known for his lyrical style.

My meeting with Buju Banton was rather unusual, rather strange.

On that day, I stepped out from my business place to go across the street to get something to eat at “Iqulah’s Restaurant,” then located on 89th Ave & 165St, in Jamaica, Queens. As I entered the crowded Restaurant, I heard someone sitting on a stool shouting, enraged with disgust, about a business card he held in his hand.

The next moment I heard the person sitting on the stool say angrily, “Ah who put my (expletive) face on (expletives) barber shop business card?”

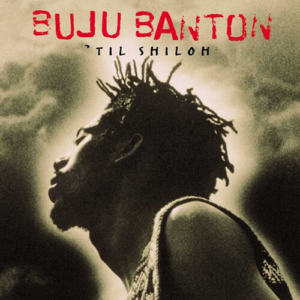

Recognizing the card in his hand, I immediately said, “I man don’t run no barber shop Ras. I man do locs.” I did use his “Till Shiloh Come” Album cover for my first business locs venture. But I could not have imagined walking into Buju cursing me out for using the picture.

After explaining exactly what I do he calmed down.

We started to reason for a moment and in the process I invited him to come with me to my store and he agreed. While in the store, I introduced him to my work crew which included Samba, my tailor from Senegal, West Africa.

Buju Banton mentioned, after realizing that we design customized fashion, that he would like me to give him a price on getting two leather sweat pants made and how much they would cost. I said sure and gave him a price of $300.

Without hesitation he paid in cash.

At that time we, at Ras Roots Creations, designed many pieces of fashion for some of the most prominent artists in the Hip Hop and Dancehall World. Ras Roots Creations did work for people like Bob Marley’s I-Trees, Luciano, Sizzler, LL Cool J. We also designed things like those Salt&Pepper Kente-Leather hats that were once a thing; a leather suit for KRS-1; hats for Just-Ice and X-Clan; to name a few.

After Samba, the tailor, took Buju’s measurements and he picked the colors and described the style he wanted we hanged out in the store for about two and a half hours until the pants were made talking about Rastafari and Dancehall culture.

Since meeting Buju Banton, many years ago, his journey has been, as he would say, “Not a easy road…Not a bed of Roses…Who feels it knows.”

‘The Gargamel’, another moniker or nickname of Buju Banton, is said to be based on the fact that his face carries a resemblance to that of the character Gargamel in kids’ cartoon series, The Smurfs. The nickname has come to carry greater significance based on the darker side of Buju’s story. Source: Reggae’s Gargamel: 10 Interesting Facts About Buju Banton —diG Jamaica. February 22, 2017.

In the musical career of Buju’s evolution, two of his songs, from his large catalogue, have caused serious controversy in Jamaica and worldwide. Those two songs are: “Love Me Browning”; a song expressing love for lighter skin women; and Boom Bye Bye, a song criticized for homophobic lyrics and inciting violence against homosexuals.

“Love Me Browning”, which was released on May 6, 1992, was a “Big Tune” that caused serious controversy. “Me Browning” forced Buju to do a counter to his own song called, “Love Black Woman” which was released on June 9, 1993. This was done to redeem Buju from the onslaught of criticism he received from a certain section of the society who thought Buju was promoting the traditional stereotype of light skin beauty over women with darker complexion.

This sentiment was echoed in this quote from the Jamaica Observer many years later, in 2017.

“The two-toned women parading on the streets wearing winter gear is testament to the fact that there’s still a market for the browning (real or chemical) in Jamaican society. But are male perceptions still skewed towards the Buju Banton ‘love mi browning’ ideal?”

“Me Browning” spoke of Banton’s preference for lighter-skinned Black women as priority in a country where the majority of the female population are Black of dark skinned.

“Mi love my car mi love my bike mi love mi money and ting, but most of all mi love mi browning.” This sentiment seem to perpetuate the traditional belief that women with darker completion are inferior to their lighter skinned counterpart.

In recognizing his misstep, Buju quickly released “Love Black Woman” which spoke of his love for women with dark complexion. But the cat was out of the bag already. “Mi nuh Stop cry, fi all Black women, respect all the girls dem with dark complexion,” came after the fact.

I am sure Buju spent many moments reflecting on his word choices and the public reaction mainly in light of the fact that his song helped to inspire the “Bleaching” craze in Jamaica.

His “Browning’ or Brown skin glorification is typical to a large percentage of the Black male population. The fact that Buju had to do a retake on the song “Mi Browning” is evidence of the active complexion politics playing out in the minds of men across the Caribbean.

Buju Banton caused worldwide controversy again in 1992 with the release of “Boom Bye Bye”. His most viral hit song to date, Boom Bye Bye ignited rage in the homosexual community in England, Canada, and particularly in America.

Recorded several years earlier in 1988, when the artist was 15 years old, this song became an anthem in Dancehall but posed the greatest threat to Buju Banton’s career. It fomented a backlash that threatened to destroy the young artist’s promising future. 1992 was an explosive year for Buju, his two most controversial songs came out that same year.

The conversations about the homosexual lifestyle had a different cultural quality (in Jamaica) than the discussion about the subject in the more industrialized societies where the discussion has been elevated to a mostly civil debate. For example, “The Sexual Offences Act 1967 is an Act of Parliament in the United Kingdom (citation 1967 c. 60). It legalized homosexual acts in England and Wales, on the condition that they were consensual, in private and between two men who had attained the age of 211. The act was passed in response to a recommendation from the Wolfenden report1.”

Conversely, the legal status of same sex relationships in Jamaica legally haven’t changed. “Jamaica had already gained its independence in 1962, and thus its buggery law adopted from the British constitution, remained intact and is still in force to this day.”

In England a LGBT Group rallied to defend the homosexual community by designing a contract for artists to commit to. This was a campaign called “Stop Murder Music” which persuaded many Dancehall artists to sign The Reggae Compassionate Act.

In July 2007, the Guardian reported that Banton had signed the Act, apparently because boycotts mounted by the organized homosexual movement were costing him money. The same article went on to say that, “in early June 2007 [he] signed [The Reggae Compassion Act] under his real name, Mark Myrie”, but that, sadly, “Buju has performed Boom Bye Bye, in whole or part, after signing the RCA and has abused gay rights groups with the epithet ‘F–k them.'” Source: Boom Bye Bye by Buju Banton – Songfacts

I had an interesting eventful opportunity to experience Gargamel, The Banton, in a very personal, un-staged environment.

The performance I walked into, where he was angry about someone (me) putting his face on a supposed barbershop business card, disappeared over time. You could feel and hear that he was a very assertive and verbose individual, but firm and confident.

Buju’s decision to spend money at my business place, even though our initial interaction was testy, was an inspiration to me. It reminds me of the expression of a concept Dr. Claude Anderson proposed in his book, “Black Labor White Wealth” where he talks about “Cultural Economics” and the importance of spending money with each other to build a business culture.

The politics built into the Jamaican psyche, earned from a plantation society, the legacy of a colonial past is still present. We must keep this in mind: Buju is a product of this environment.

Buju Banton the Grammy-winning singer, Rasta artist, has had a roller coaster life. In 2011, Buju was sentenced to 10 years in a United States federal prison for his conviction for conspiracy to possess and distribute cocaine. In addition to the conspiracy charge, Banton was also found guilty of another drug trafficking offense and a gun charge. But the sentence was reduced to seven years and the gun charge was dropped.

Many in the community are suspicious of the motives on the part of some of Buju’s most powerful critics, as it relates to his legal troubles.

But, then again, Buju seems to have stepped on a few legal lines and compromised himself to some degree. He paid the price and learn some lessons.

Hopefully, Buju Banton, with whom I had a most memorable meeting, once upon a time in Queens, New York, is now moving on in life to a promising future ahead.

Ras Kefim, the author of Deception In the Name Of the Lord, is a New York-based author and business entrepreneur who through his various businesses (including being a master tailor and hat-maker) has done work for many local luminaries, particularly within the entertainment\cultural space. Ras Kefim can be contacted via e-mail at [email protected] or by phone at 1-347 369 8280.

Buy Deception In the Name Of the Lord