By Jared O. Bell

Photos: YouTube Screenshots\Wikimedia Commons

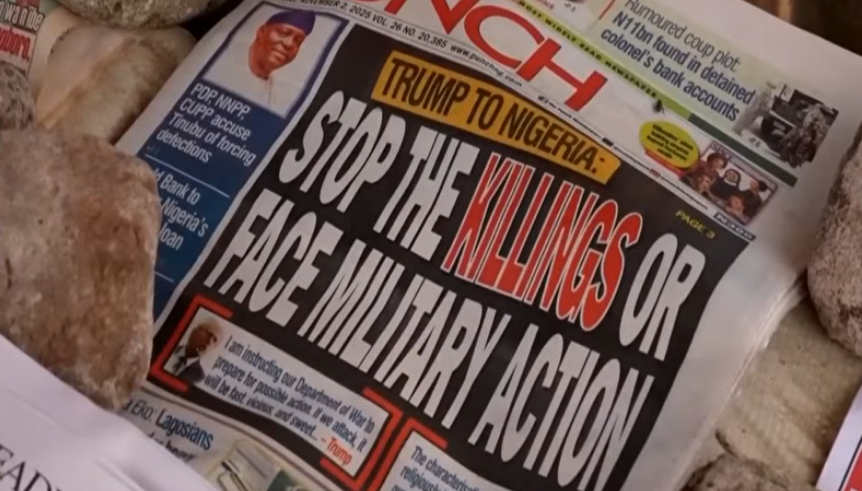

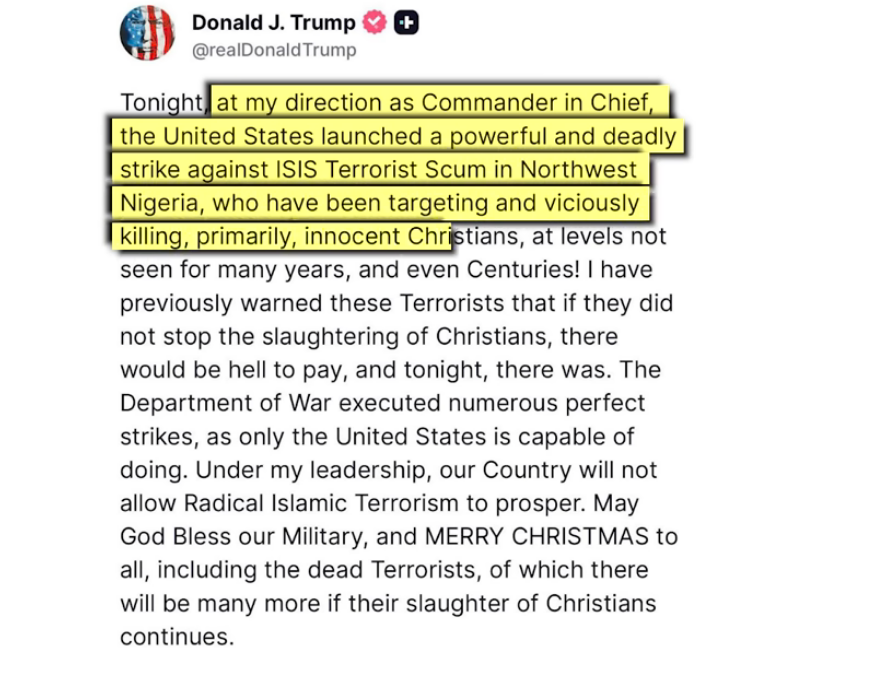

For anyone paying even modest attention to the current administration’s foreign policy posture, a Christmas Day bombing justified as “protecting Christians from ISIS” in Nigeria was neither shocking nor clarifying. It fits a familiar rhetorical script. What it did not fit was reality.

Nigeria’s violence is real, devastating, and long-standing, but it is not best understood as a campaign of religious extermination. Insecurity there is driven primarily by land disputes, criminal networks, resource competition, ethnic fragmentation, and profound state fragility. Religious identity often becomes the language through which these conflicts are narrated, but it is not their root cause. Reducing Nigeria’s crisis to a story of Christian genocide is not only analytically lazy, it is misleading.

What makes the Christmas Day strike especially troubling is its direct contradiction of the administration’s own stated national security doctrine. That strategy criticizes decades of U.S. foreign policy built on vague platitudes masquerading as strategy and calls instead for disciplined, outcome-driven statecraft with clear political end states.

Yet a one-off bombing on Christmas Day, absent any coherent diplomatic or political framework, is precisely the behavior the strategy claims to reject. What is the actual political or strategic objective? To scare ISIS? To coerce Nigerian authorities into protecting Christians from a genocide that U.S. officials themselves have not demonstrated exists? If there is a theory of change here, it has not been articulated, because it likely does not exist.

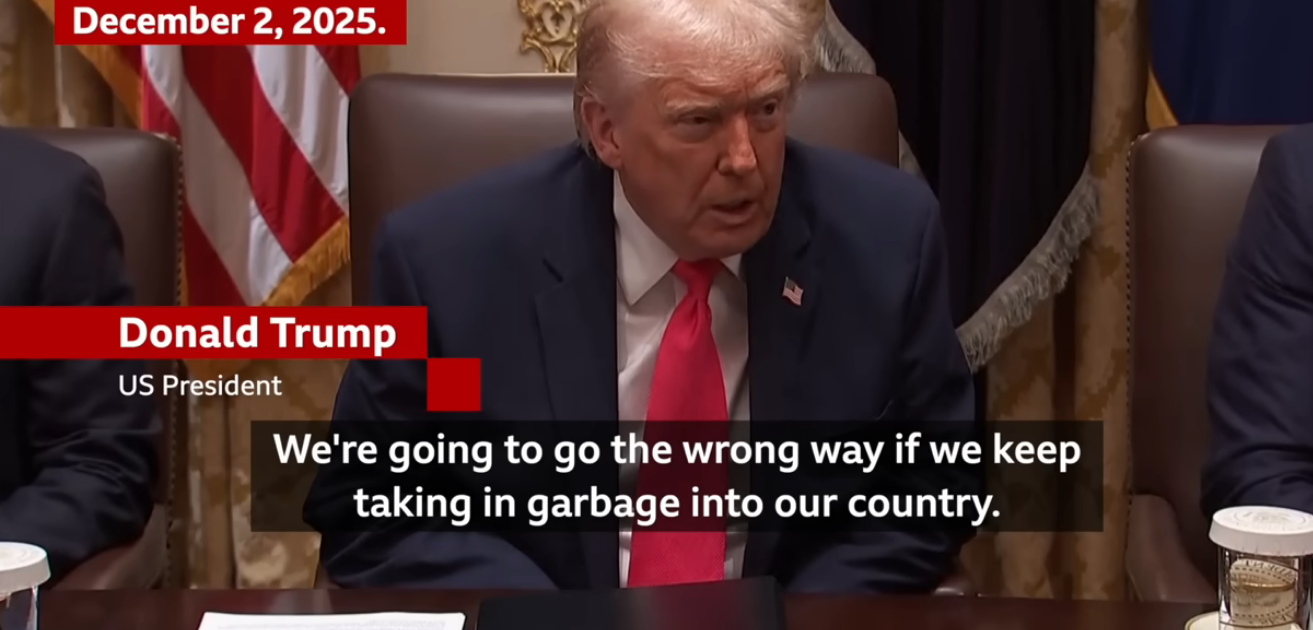

The irony is hard to miss. While the administration claims to be acting on behalf of Nigerian Christians, Nigerians themselves remain subject to a partial U.S. visa ban and heightened entry restrictions that, in practice, sharply limit access. This restricts lawful migration pathways for students, professionals, families, asylum seekers, and religious minorities alike, treating an entire population as a presumptive security risk rather than as individuals with rights and agency. Bombing in the name of Nigerian Christians abroad while partially closing America’s doors to them at home does not project moral clarity. It exposes a foreign policy that instrumentalizes human suffering rhetorically while reproducing exclusion materially.

The selectivity of outrage is equally revealing. While Nigeria receives outsized rhetorical and military attention, the administration has been far quieter about Sudan. Thousands of civilians, including Christians, have been killed in Sudan amid mass atrocities carried out by the Rapid Support Forces, particularly in Darfur. U.N. investigators and human-rights groups warn that ethnically targeted violence, church destruction, and attacks on religious minorities there approach genocidal levels. The disparity in attention raises uncomfortable questions about consistency and motive.

This is not an isolated set of decisions but a recurring pattern. Complex global crises are simplified, sensationalized, and weaponized for domestic political signaling rather than addressed through serious diplomacy, multilateral engagement, or long-term strategy. From fantastical claims of a genocide facing Afrikaners in South Africa to open-ended counterterrorism strikes in Somalia conducted without a clear political end state, spectacle substitutes for strategy.

This pattern is also visible in the administration’s hostility toward Venezuela. If the objective is regime change, what happens if it succeeds? Who governs, with what legitimacy, and with what capacity to stabilize a country already devastated by poverty, criminal networks, and institutional collapse? And if regime change fails, is there a diplomatic off-ramp, or does coercion simply become indefinite policy? Drug trafficking is a serious regional problem, but it extends far beyond any single leader. Removing Nicolás Maduro from power would not resolve the structural drivers of the trade, suggesting motivations that go well beyond counternarcotics alone.

Lest we forget history. The United States spent decades using sanctions, covert action, and isolation to unseat Fidel Castro. He remained in power until his death, and the political system he built still governs Cuba. Pressure without a viable political settlement often hardens into permanence rather than producing change.

The intervention in Nigeria raises the same strategic questions about rationale, proportionality, and end goals. Are these bombings symbolic gestures or the start of an open-ended campaign? If they continue, what is the theory of change, and what is supposed to be different on the ground months or a year from now? Conservative talking points erase the real drivers of violence–land competition, resource scarcity, criminality, and state weakness–replacing them with a simplified narrative of religious persecution. That framing is especially questionable given that residents and local officials report the targeted town of Jabo had no history of interreligious violence and no known ISIS presence.

Nor is this approach securing legitimacy at home. Polling by CBS News shows roughly 70 percent of Americans oppose armed conflict in Venezuela. While polling specific to Nigeria has yet to emerge, past public resistance to open-ended foreign interventions suggests this bombing is unlikely to enjoy sustained domestic support.

What did earn the United States legitimacy abroad was sustained engagement with root causes through foreign assistance. Long-term investments in governance, development, conflict prevention, and humanitarian relief addressed instability before it metastasized into violence. Foreign assistance was imperfect, and I have no shortage of criticism for how it was often designed and politicized. But it remained one of the few tools that allowed the United States to exercise influence without coercion.

That credibility has now been hollowed out. By dismantling development and democracy programs and slashing humanitarian aid, the administration has eroded a core pillar of American soft power. Humanitarian organizations and public-health analysts estimate that disruptions linked to recent foreign-assistance cuts have already contributed to over 600,000 preventable deaths worldwide. You cannot bomb your way to legitimacy after defunding the very systems designed to prevent conflict and save lives.

The bottom line is this. Manufactured crises and political theater are fooling no one. They are not making the world safer, they are not advancing U.S. interests, and they are certainly not putting America first. Absent strategy, planning, and clear political end states, they amount to performative uses of force that waste resources at a time when many Americans are already feeling the strain of a rising cost of living. Endless, contradictory conflicts sharpen neither U.S. credibility abroad nor security at home. We deserve better.

Jared O. Bell, PhD, syndicated with PeaceVoice, is a former U.S. diplomat and scholar of human rights and transitional justice, dedicated to advancing global equity and systemic reform.