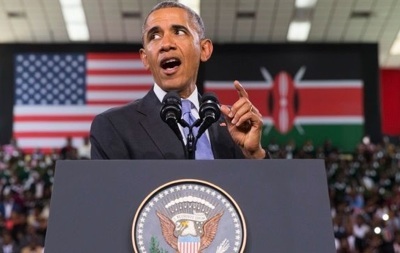

Safaricom Indoor Arena

Nairobi, Kenya

PRESIDENT OBAMA: Habari Zenu! Wakenya mpo? It is great to be back in Kenya. Thank you so much for this extraordinary welcome. I know it took a few years, but as President I try to keep my promises, and I said I was going to come, and I’m here.

Everybody, go ahead and have a seat. I’m going to be talking for a while. Relax.

I want to thank my sister, Auma, for a wonderful introduction. I’m so glad that she could be with us here today. And it was — as she said, it was Auma who first guided me through Kenya almost 30 years ago.

To President Kenyatta, I want to thank you once again for the hospitality that you’ve shown to me — and for our work together on this visit, and for being here today. It’s a great honor.

I am proud to be the first American President to come to Kenya — and, of course, I’m the first Kenyan-American to be President of the United States. That goes without saying.

But, as Auma was saying, the first time I came to Kenya, things were a little different. When I arrived at Kenyatta Airport, the airline lost my bags.

That doesn’t happen on Air Force One. They always have my luggage on Air Force One. As she said, Auma picked me up in an old Volkswagon Beetle, and think the entire stay I was here it broke down four or five times. We’d be on the highway, we’d have to call the juakali — he’d bring us tools. We’d be sitting there, waiting. And I slept on a cot in her apartment. Instead of eating at fancy banquets with the President, we were drinking tea and eating Ugali — and Sukumawiki.

So there wasn’t a lot of luxury. Sometimes the lights would go out. They still do — is that what someone said? But there was something more important than luxury on that first trip, and that was a sense of being recognized, being seen. I was a young man and I was just a few years out of University. I had worked as a community organizer in low-income neighborhoods in Chicago. I was about to go to law school. And when I came here, in many ways I was a Westerner, I was an American, unfamiliar with my father and his birthplace, really disconnected from half of my heritage. And at that airport, as I was trying to find my luggage, there was a woman there who worked for the airlines, and she was helping fill out the forms, and she saw my name and she looked up and she asked if I was related to my father, who she had known. And that was the first time that my name meant something. And that was recognized.

And over the course of several weeks, I’d meet my brothers and aunts and uncles. I traveled to Alego, the village where my family was from. I saw the graves of my father and my grandfather. And I learned things about their lives that I could have never learned through books. And in many ways, their lives offered snapshots of Kenya’s history, but they also told us something about the future.

My grandfather, for example, he was a cook for the British. And as I went through some of his belongings when I went up-country, I found the passbook he had had to carry as a domestic servant. It listed his age and his height, his tribe, listed the number of teeth he had missing. And he was referred to as a boy, even though he was a grown man, in that passbook.

And he was in the King’s African Rifles during the Second World War, and was taken to the far reaches of the British Empire — all the way to Burma. And back home after the war, he was eventually detained for a time because he was linked to a group that opposed British rule. And eventually he was released. He forged a home for himself and his family. He earned the respect of his village, lived a life of dignity — although he had a well-earned reputation for being so strict that everybody was scared of him and he became estranged from part of his family.

So that was his story. And then my father came of age as Kenyans were pursuing independence, and he was proud to be a part of that liberation generation. And next to my grandfather’s papers, I found letters that he had written to 30 American universities asking for a chance to pursue his dream and get a scholarship. And ultimately, one university gave him that chance — the University in Hawaii. And he would go on to get an education and then return home.

And here, at first he found success as an economist and worked with the government. But ultimately, he found disappointment — in part because he couldn’t reconcile the ideas that he had for his young country with the hard realities that had confronted him.

And I think sometimes about what these stories tell us, what the history and the past tell us about the future. They show the enormous barriers to progress that so many Kenyans faced just one or two generations ago. This is a young country. We were talking last night at dinner — the President’s father was the first President. We’re only a generation removed. And the daily limitations — and sometimes humiliations — of colonialism — that’s recent history. The corruption and cronyism and tribalism that sometimes confront young nations — that’s recent history.

But what these stories also tell us is an arch of progress — from foreign rule to independence; from isolation to education, and engagement with a wider world. It speaks of incredible progress. So we have to know the history of Kenya, just as we Americans have to know our American history. All people have to understand where they come from. But we also have to remember why these lessons are important.

We know a history so that we can learn from it. We learn our history because we understand the sacrifices that were made before, so that when we make sacrifices we understand we’re doing it on behalf of future generations.

There’s a proverb that says, “We have not inherited this land from our forebears, we have borrowed it from our children.” In other words, we study the past so it can guide us into the future, and inspire us to do better.

And when it comes to the people of Kenya — particularly the youth — I believe there is no limit to what you can achieve. A young, ambitious Kenyan today should not have to do what my grandfather did, and serve a foreign master. You don’t need to do what my father did, and leave your home in order to get a good education and access to opportunity. Because of Kenya’s progress, because of your potential, you can build your future right here, right now.

Now, like any country, Kenya is far from perfect, but it has come so far in just my lifetime. After a bitter struggle, Kenyans claimed their independence just a few years after I was born. And after decades of one party-rule, Kenya embraced a multi-party system in the 1990s, just as I was beginning my own political career in the United States.

Tragically, just under a decade ago, Kenya was nearly torn apart by violence at the same time that I was running for my first campaign for President. And I remember hearing the reports of thousands of innocent people being killed or driven from their homes. And from a distance, it seemed like the Kenya that I knew — a Kenya that was able to reach beyond ethnic and tribal lines — that it might split apart across those lines of tribe and ethnicity.

But look what happened. The people of Kenya chose not to be defined by the hatreds of the past — you chose a better history. The voices of ordinary people, and political leaders and civil society did not eliminate all these divisions, but you addressed the divisions and differences peacefully. And a new constitution was put in place, declaring that “every person has inherent dignity — and the right to have that dignity respected and protected.” A competitive election went forward — not without problems, but without the violence that so many had feared. In other words, Kenyans chose to stay together. You chose the path of Harambee.

And in part because of this political stability, Kenya’s economy is also emerging — and the entrepreneurial spirit that people rely on to survive in the streets of Kibera can now be seen in new businesses across the country. From the city square to the smallest villages, MPesa is changing the way people use money. New investment is making Kenya a hub for regional trade. When I came here as a U.S. senator, I pointed out that South Korea’s economy was the same as Kenya’s when I was born, and then was 40 times larger than Kenya’s. Think about that. It started at the same place — South Korea had gone here, and Kenya was here. But today, that gap has been cut in half just in the last decade. Which means Kenya is making progress.

And meanwhile, Kenya continues to carve out a distinct place in the community of nations: As a source of peacekeepers for places torn apart by conflict, a host for refugees driven from their homes. A leader for conservation, following the footprints of Wangari Maathai. Kenya is one of the places on this continent that truly observes freedom of the press, and their fearless journalists and courageous civil society members. And in the United States, we see the legacy of Kip Keino every time a Kenyan wins one of our marathons. And maybe the First Lady of Kenya is going to win one soon. I told the President he has to start running with his wife. We want him to stay fit.

So there’s much to be proud of — much progress to lift up. It’s a good-news story. But we also know the progress is not complete. There are still problems that shadow ordinary Kenyans every day — challenges that can deny you your livelihood, and sometimes deny you lives.

As in America — and so many countries around the globe — economic growth has not always been broadly shared. Sometimes people at the top do very well, but ordinary people still struggle. Today, a young child in Nyanza Province is four times more likely to die than a child in Central Province — even though they are equal in dignity and the eyes of God. That’s a gap that has to be closed.

A girl in Rift Valley is far less likely to attend secondary school than a girl in Nairobi. That’s a gap that has to be closed. Across the country, one study shows corruption costs Kenyans 250,000 jobs every year — because every shilling that’s paid as a bribe could be put into the pocket of somebody who’s actually doing an honest day’s work.

And despite the hard-earned political progress that I spoke of, those political gains still have to be protected. New laws and restrictions could close off the space where civil society gives individual citizens a voice and holds leaders accountable. Old tribal divisions and ethnic divisions can still be stirred up. I want to be very clear here — a politics that’s based solely on tribe and ethnicity is a politics that’s doomed to tear a country apart. It is a failure — a failure of imagination.

Of course, here, in Kenya, we also know the specter of terrorism has touched far too many lives. And we remember the Americans and Kenyans who died side by side in the attack on our embassy in the ‘90s. We remember the innocent Kenyans who were taken from us at Westgate Mall. We weep for the nearly 150 people slaughtered at Garissa — including so many students who had such a bright future before them. We honor the memory of so many other innocent Kenyans whose lives have been lost in this struggle.

So Kenya is at a crossroads — a moment filled with peril, but also enormous promise. And with the rest of my time here today, I’d like to talk about how you can seize the moment, how you can make sure we leave behind a world that’s better — a world that we borrowed from our children.

When I first came to sub-Saharan Africa as President, I made clear my strong belief that the future of Africa is up to Africans. For too long, I think that many looked to the outside for salvation and focused on somebody else being at fault for the problems of the continent. And as my sister said, ultimately we are each responsible for our own destiny. And I’m here as President of a country that sees Kenya as an important partner. I’m here as a friend who wants Kenya to succeed.

And the pillars of that success are clear: Strong democratic governance; development that provides opportunity for all people and not just some; a sense of national identity that rejects conflict for a future of peace and reconciliation.

And today, we can see that future for Kenya on the horizon. But tough choices are going to have to be made in order to arrive at that destination. In the United States, I always say that what makes America exceptional is not the fact that we’re perfect, it’s the fact that we struggle to improve. We’re self-critical. We work to live up to our highest values and ideals, knowing that we’re not always going to achieve them perfectly, but we keep on trying to perfect our union.

And what’s true for America is also true for Kenya. You can’t be complacent and accept the world just as it is. You have to imagine what the world might be and then push and work toward that future. Progress requires that you honestly confront the dark corners of our own past; extend rights and opportunities to more of your citizens; see the differences and diversity of this country as a strength, just as we in America try to see the diversity of our country as a strength and not a weakness. So you can choose the path to progress, but it requires making some important choices.

First and foremost, it means continuing down the path of a strong, more inclusive, more accountable and transparent democracy.

Democracy begins with a peacefully-elected government. It begins with elections. But it doesn’t stop with elections. So your constitution offers a road map to governance that’s more responsive to the people — through protections against unchecked power, more power in the hands of local communities. For this system to succeed, there also has to be space for citizens to exercise their rights.

And we saw the strength of Kenya’s civil society in the last election, when groups collected reports of incitement so that violence could be stopped before it spun out of control. And the ability of citizens to organize and advocate for change — that’s the oxygen upon which democracy depends. Democracy is sometimes messy, and for leaders, sometimes it’s frustrating. Democracy means that somebody is always complaining about something. Nobody is ever happy in a democracy about their government. If you make one person happy, somebody else is unhappy. Then sometimes somebody who you made happy, later on, now they’re not happy. They say, what have you done for me lately? But that’s the nature of democracy. That’s why it works, is because it’s constantly challenging leaders to up their game and to do better.

And such civic participation and freedom is also essential for rooting out the cancer of corruption. Now, I want to be clear. Corruption is not unique to Kenya. I mean, I want everybody to understand that there’s no country that’s completely free of corruption. Certainly here in the African continent there are many countries that deal with this problem. And I want to assure you I speak about it wherever I go, not just here in Kenya. So I don’t want everybody to get too sensitive.

But the fact is, too often, here in Kenya — as is true in other places — corruption is tolerated because that’s how things have always been done.

People just think that that is sort of the normal state of affairs. And there was a time in the United States where that was true, too. My hometown of Chicago was infamous for Al Capone and the Mob and organized crime corrupting law enforcement. But what happened was that over time people got fed up, and leaders stood up and they said, we’re not going to play that game anymore. And you changed a culture and you changed habits.

Here in Kenya, it’s time to change habits, and decisively break that cycle. Because corruption holds back every aspect of economic and civil life. It’s an anchor that weighs you down and prevents you from achieving what you could. If you need to pay a bribe and hire somebody’s brother — who’s not very good and doesn’t come to work — in order to start a business, well, that’s going to create less jobs for everybody. If electricity is going to one neighborhood because they’re well-connected, and not another neighborhood, that’s going to limit development of the country as a whole. (Applause.) If someone in public office is taking a cut that they don’t deserve, that’s taking away from those who are paying their fair share.

So this is not just about changing one law — although it’s important to have laws on the books that are actually being enforced. It’s important that not only low-level corruption is punished, but folks at the top, if they are taking from the people, that has to be addressed as well. But it’s not something that is just fixed by laws, or that any one person can fix. It requires a commitment by the entire nation — leaders and citizens — to change habits and to change culture.

Tough laws need to be on the books. And the good news is, your government is taking some important steps in the right direction. People who break the law and violate the public trust need to be prosecuted. NGOs have to be allowed to operate who shine a spotlight on what needs to change. And ordinary people have to stand up and say, enough is enough. It’s time for a better future.

And as you take these steps, I promise that America will continue to be your partner in supporting investments in strong, democratic institutions.

Now, we’re also going to work with you to pursue the second pillar of progress, and that is development that extends economic opportunity and dignity for all of Kenya’s people.

America partners with Kenya in areas where you’re making enormous progress, and we focus on what Kenyans can do for themselves and building capacity; on entrepreneurship, where Kenya is becoming an engine for innovation; on access to power, where Kenya is developing clean energy that can reach more people; on the important issue of climate change, where Kenya’s recent goal to reduce its emissions has put it in the position of being a leader on the continent; on food security, where Kenyan crops are producing more to meet the demands of your people and a global market; and on health, where Kenya has struck huge blows against HIV/AIDS and other diseases, while building up the capacity to provide better care in your communities.

America is also partnering with you on an issue that’s fundamental to Kenya’s future: We are investing in youth. We are investing in the young people of Kenya and the young people of this continent. Robert F. Kennedy once said, “It is a revolutionary world that we live in,” and “it is the young people who must take the lead.” It’s the young people who must take the lead.

So through our Young African Leaders Initiative — we are empowering and connecting young people from across the continent who are filled with energy and optimism and idealism, and are going to take Africa to new heights. And these young people, they’re not weighted down by the old ways. They’re creating a new path. And these are the elements for success in this 21st century.

To continue down this path of progress, it will be vital for Kenya to recognize that no country can achieve its full potential unless it draws on the talents of all its people — and that must include the half of Kenyans — maybe a little more than half –who are women and girls. Now, I’m going to spend a little time on this just for a second. Every country and every culture has traditions that are unique and help make that country what it is. But just because something is a part of your past doesn’t make it right. It doesn’t mean that it defines your future.

Look at us in the United States. Recently, we’ve been having a debate about the Confederate flag. Some of you may be familiar with this. This was a symbol for those states who fought against the Union to preserve slavery. Now, as a historical artifact, it’s important. But some have argued that it’s just a symbol of heritage that should fly in public spaces. The fact is it was a flag that flew over an army that fought to maintain a system of slavery and racial subjugation. So we should understand our history, but we should also recognize that it sends a bad message to those who were liberated from slavery and oppression.

And in part because of an unspeakable tragedy that took place recently, where a young man who was a fan of the Confederate flag and racial superiority shot helpless people in a church, more and more Americans of all races are realizing now that that flag should come down. Just because something is a tradition doesn’t make it right.

Well, so around the world, there is a tradition of repressing women and treating them differently, and not giving them the same opportunities, and husbands beating their wives, and children not being sent to school. Those are traditions. Treating women and girls as second-class citizens, those are bad traditions. They need to change. They’re holding you back.

Treating women as second-class citizens is a bad tradition. It holds you back. There’s no excuse for sexual assault or domestic violence. There’s no reason that young girls should suffer genital mutilation. There’s no place in civilized society for the early or forced marriage of children. These traditions may date back centuries; they have no place in the 21st century.

These are issues of right and wrong — in any culture. But they’re also issues of success and failure. Any nation that fails to educate its girls or employ its women and allowing them to maximize their potential is doomed to fall behind in a global economy.

You know, we’re in a sports center. Imagine if you have a team and you don’t let half of the team play. That’s stupid. That makes no sense. And the evidence shows that communities that give their daughters the same opportunities as their sons, they are more peaceful, they are more prosperous, they develop faster, they are more likely to succeed. That’s true in America. That’s true here in Kenya. It doesn’t matter.

And that’s why one of the most successful development policies you can pursue is giving girls and education, and removing the obstacles that stand between them and their dreams. And by the way, if you educate girls — they grow up to be moms — and they, because they’re educated, are more likely to produce educated children. So Kenya will not succeed if it treats women and girls as second-class citizens. I want to be very clear about that.

Now, this leads me to the third pillar of progress, and that’s choosing a future of peace and reconciliation.

There are real threats out there. President Kenyatta and I spent a lot of time discussing the serious threat from al-Shabaab that Kenya faces. The United States faces similar threats of terrorism. We are grateful for the sacrifices made by Kenyans on the front lines as part of AMISOM. We’re proud of the efforts that we’re making to strengthen Kenya’s capabilities through our new Security Governance Initiative. We’re going to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with you in this fight against terrorism for as long as it takes.

But, as I mentioned yesterday, it is important to remember that violent extremists want us to turn against one another. That’s what terrorists typically try to exploit. They know that they are a small minority; they know that they can’t win conventionally. So what they try to do is target societies where they can exploit divisions. That’s what happens in Iraq. That’s what happens around the world. That’s what happened in Northern Ireland. Terrorists who try to sow chaos, they must be met with force and they must also be met, though, with a forceful commitment to uphold the rule of law, and respect for human rights, and to treat everybody who’s peaceful and law-abiding fairly and equally.

Extremists who prey on distrust must be defeated by communities who stand together and stand for something different. And the most important example here is, is that the United States and Kenya both have Muslim minorities, but those minorities make enormous contributions to our countries. These are our brothers, they are our sisters. And so in both our countries, we have to reject calls that allow us to be divided.

This is true for any diverse society. And Kenya is rich with diversity — with many dozens of tribes and ethnicities, and languages and religious groups. And time and again, just as we’ve seen the dangers of religious or ethnic violence, we’ve seen that Kenya is stronger when Kenyans stand united — with a sense of national identity. That was the case on December 12, 1963, when cities and villages across this country celebrated the birth of a nation. It was true in 2010, when Kenya replaced the anarchy of ethnic violence with the order of a new constitution.

So we can all appreciate our own identities, our bloodlines, our beliefs, our backgrounds — that tapestry is what makes us who we are. But the history of Africa — which is both the cradle of human progress and a crucible of conflict — shows us that when define ourselves narrowly, in opposition to somebody just because they’re of a different tribe, or race, or religion — and we ignore who is a good person or a bad person, are they working hard or not, are they honest or not, are they peaceful or violent — when we start making distinctions solely based on status and not what people do, then we’re taking the wrong path and we inevitably suffer in the end.

This is why Martin Luther King called on people to be judged not by the color of their skin but the content of their character. And in the same way, people should not be judged by their last name, or their religious faith, but by their content of their character and how they behave. Are they good citizens? Are they good people?

In the United States, we embrace the motto: E Pluribus Unum. In Latin, that means, out of many, one. In Kenya, Harambee — we are in this together. Whatever the challenge, you will be stronger if you face it not as Christians or Muslims, Masai, Kikuyu, Luo, any other tribe — but as Kenyans. And ultimately, that unity is the source of strength that will empower you to seize this moment of promise. That’s what will help you root out corruption. That’s what will strengthen democratic institutions. That’s what will help you combat inequality. That’s what will help you extend opportunity, and educate youth, and face down threats, and embrace reconciliation.

So I want to say particularly to the young people here today, Kenya is on the move. Africa is on the move. You are poised to play a bigger role in this world — as the shadows of the past are replaced by the light that you offer an increasingly interconnected world. And in the light of this new day, we have to learn to see ourselves in one another. We have to see that we are connected, our fates are bound together. Because, in the end, we’re all part of one tribe — the human tribe. And no matter who we are, or where we come from, or what we look like, or who we love, or what God we worship, we’re connected. Our fates are bound up with one another.

Kenya holds within it all that diversity. And with diversity, sometimes comes difficulty. But I look to Kenya’s future filled with hope. And I’m hopeful because of you, the people of Kenya, especially the young people.

There are some amazing examples of what’s going on right now with young people. I’m hopeful because of a young man named Richard Ruto Todosia. Richard helped build Yes Youth Can — I like the phrase, Yes Youth Can — It became one of the most prominent civil society organizations in Kenya, with over one million members. And after the violence of 2007, 2008, Yes Youth Can stood up to incitement, helped bring opportunity to young people in places that were scarred by conflict. That’s the kind of young leadership that we need.

I’m hopeful because of a young woman named Josephine Kulea. So Josephine founded Samburu Girls Foundation. And she’s already helped to rescue over 1,000 girls from abuse and forced marriage, and helped place them in schools. A member of the Samburu tribe herself, she’s personally planned rescue missions to help girls as young as 6 years old. And she explains that, “The longer a girl is in school, everything for her — for her income, for her family, for this country — everything changes.” She gives me hope.

I’m hopeful because of a young woman named Jamila Abass. So Jamila founded Mfarm, which is a mobile platform that is already used by over 14,000 people across Kenya. Mfarm makes it easy for farmers to get information that lets them match their crops with what the market demands. And studies show that it can help farmers double their sales. So here’s what Jamila said: “I love Kenya because you feel you are home anywhere you go.”

Home anywhere you go — that’s the Kenya that welcomed me nearly 30 years ago as a young man. You helped make me feel at home. And standing here today as President of the United States, when I think about those young people and all the young people in attendance here, you still make me feel at home. And I’m confident that your future is going to be written across this country and across this continent by young people like you — young men and women who don’t have to struggle under a colonial power; who don’t have to look overseas to realize your dreams. Yes, you can realize your dreams right here, right now.

“We have not inherited this land from our forebears, we have borrowed it from our children.” So now is the time for us to do the hard work of living up to that inheritance; of building a Kenya where the inherent dignity of every person is respected and protected, and there’s no limit to what a child can achieve.

I am here to tell you that the United States of America will be a partner for you every step of the way.

God bless you. Thank you. Asante sana.