Photos: CCR\Witness Against Torture

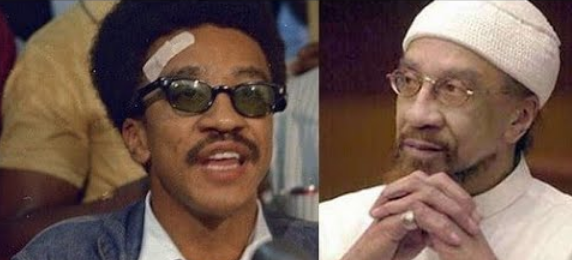

October 18, 2021, New York ‒ Today, a man who spent nearly five years in a so-called Communication Management Unit (CMU) continued his quest to clear his name. Arguing on his behalf in the D.C. Court of Appeals, Center for Constitutional Rights attorneys presented extensive evidence showing that the federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) had denied him due process rights guaranteed by the Constitution.

“I was thrown into this horrific facility with no means to challenge my placement,” said Kifah Jayyousi, who was released from prison in 2017. He is seeking to have all CMU-related allegations expunged from his BOP record. “The harsh conditions, mistreatment, religious discrimination, and harassment turned the CMU into a cold storage labyrinth of Muslim prisoners.”

In 2007, Mr. Jayyousi was convicted of terrorism-related charges stemming from a charity he ran despite the fact that he denied the charges and the judge gave him the minimum sentence of twelve years and eight months, saying there was no evidence linking him to any actual act of terrorism. The following year, he was moved to the CMU.

Designed to isolate certain people from both other prisoners and the outside world, the CMU is a product of the early years of the “War on Terror.” BOP created the first CMU in Terre Haute, Indiana, in 2006, and added another in Marion, Illinois, in 2008. Although the CMUs represented a dramatic policy change, BOP did not provide the required public notice. Nor did it develop clear criteria or procedures for placement and retention; in fact, when Mr. Jayyousi was sent to the Terre Haute CMU in 2008, there were still no written criteria or procedures at all.

Under the vague criteria that eventually emerged, only a few hundred of the thousands of people in prison eligible for CMUs have been placed in them, and most have been Muslim. According to the most recent available statistics, while only about six percent of the federal prison population is Muslim, nearly 60 percent of people in CMUs are Muslim.

People held in CMUs face severe restrictions. Unlike all other prisoners in the federal system, they are banned from all physical contact with visitors. They are allowed few phone calls and denied most of the work and educational opportunities available to other prisoners. The prolonged, indefinite duration compounds these hardships; while administrative segregation and other forms of solitary confinement usually last a few weeks, CMU confinement goes on for years, without a clear process for getting out. Mr. Jayyousi was not permitted to touch his wife, young children, or parents for almost five years.

“Although I was ruthlessly prosecuted and convicted of a crime I didn’t commit, my family, especially my children, suffered the greatest harm and permanent mental scarring,” said Mr. Jayyousi. “Years after my release, the non-contact visits behind a dirty pane of glass in a 4’x5′ cramped steely room can never be forgotten.”

While people transferred to a CMU are given a short summary of the purported reasons for their placement, Center for Constitutional Rights attorneys produced evidence to the court showing that the BOP Regional Director who made CMU placement decisions never wrote his reasons down; so the reason on the notice could be the same, or completely different from the actual reason for placement. Although people held in CMUs are purportedly able to rebut the reasons for their placement via the Administrative Remedy Program, not a single person has secured release this way. People put in the CMU are also given erroneous ‒ or even impossible ‒ instructions for earning their way out.

Mr. Jayyousi was told that he was placed in a CMU in part because his offense conduct included using “religious training to recruit others” for criminal acts, and because he communicated with and assisted al Qaeda. When Mr. Jayyousi used the Administrative Remedy Program to explain that this information was incorrect, he was ignored, and the BOP instead stated that different reasons, including secret evidence, supported his placement. More than three years passed before a person empowered to order Mr. Jayyousi’s release considered his case. When he was finally transferred, he was not given a reason.

“The law is clear,” said Rachel Meeropol, Senior Staff attorney for the Center for Constitutional Rights, who argued the case today. “Prisoners moved into restrictive units must be given notice of the factual basis for placement, an opportunity to be heard, and meaningful periodic review. The Bureau of Prisons denied Mr. Jayyousi all three.”

Overlooking ample undisputed evidence of due process violations, the district court ruled for the government in 2020. Today’s appeal of that decision is the latest development in more than a decade of litigation. The Center for Constitutional Rights filed this lawsuit, Aref v. Garland, as Aref v. Holder in 2010. There were initially multiple plaintiffs, all low- or medium-security prisoners designated to the CMU despite spotless or near-spotless disciplinary records. Not a single one had been disciplined for any communications-related infraction or any significant offense in the previous decade. For all of them, the process that had landed them in the CMU and kept them there was tainted by factual errors, missing paper trails, and/or discrimination.

It is this process that Mr. Jayyousi, the sole remaining plaintiff, is challenging on constitutional grounds. In today’s appellate argument, the government contended that his case is moot because he had been released from prison. But the law says a case becomes moot when a court is no longer able to provide relief, and the court can still provide relief to Mr. Jayyousi in the form of expungement. The allegations in his CMU records may impact his pending motion to modify his 20-year term of supervised release, and the BOP can still share these with other law enforcement agencies. Without expungement, Mr. Jayyousi faces significant potential harm.

“Thirteen years later, these fabricated charges are still a threat to our client,” said Meeropol. “And the Kafkaesque process he’s challenging is still harming prisoners. Like many other policies and mechanisms established by the U.S. government in the long wake of 9/11, the CMU is a discriminatory, due process disaster. It should be a relic.” The law firm Weil Gotshal & Manges LLP and attorney Kenneth A. Kreuscher are co-counsel in the case.

For more information, visit the Center for Constitutional Rights’ case page and CMU factsheet.