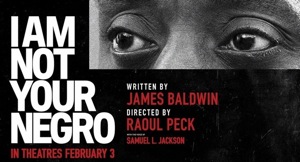

During a recent interview to promote his new documentary “I Am Not Your Negro,” I asked filmmaker Raoul Peck whether James Baldwin, the subject of the film, would have been more surprised by the election of Barack Obama as president of the United States in 2008 or the election of Donald Trump in 2016.

“Baldwin wouldn’t have been surprised by anything…” Peck said.

I may not have made myself clear in posing the question to Peck, who made the acclaimed biopic “Lumumba” about the life and brutal murder of Congo’s independence hero Patrice Lumumba in 2000.

Judging by “I Am Not Your Negro,” which opens in theaters around the nation on Friday, February 3, it seems Baldwin would have been more surprised by Obama’s election than Donald Trump’s.

Baldwin believed that unless White Americans acknowledged and dealt with their deep-seated racism which is based on fear, guilt, and not wanting Blacks in this country, racism will remain an immutable part of American society.

This remarkable film reveals how prescient many of Baldwin’s observations were. In one scene, however, he was ultimately proven “wrong”; given the racism then, and the racism that persists today, he can be excused. The documentary shows Robert Kennedy, in a 1968 interview, responding to a question about race relations in America. Yes, even though racism remained pervasive he insisted that things had improved; he could see the day, 40 years in the future, where the country could have a Black president.

Baldwin, elsewhere, responds to Kennedy’s observation. In the streets of Harlem, Kennedy’s prediction was crazy talk Baldwin says, without using those exact same words.

In 2008, the nation elected Barack Obama as the country’s first Black president. However, Baldwin wasn’t entirely wrong either. He knew the intensity of American racism. He may not have envisioned that a Black man could be elected president while the the same level of racism he observed in the 1960s persisted; and even intensified in the years after his death.

The timing of Peck’s documentary is superb. There are scenes showing 1960s protests against racial injustice and segregation. More than half a century later, some of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign rallies –“Make America Great Again”– evoked memories of those days. The election season ended with Trump, a candidate who blatantly played up racism, religious bigotry, xenophobia, and misogyny, in the White House. Baldwin would not have been surprised.

Peck’s film uses notes from Baldwin’s unfinished book, Remember This House, and several clips of interviews he gave over the years. The voiceover of words written by Baldwin is by Samuel L. Jackson.

Baldwin never got to complete more than 30 pages of Remember This House, a planned book about his friendship with three iconic freedom-fighters: Medgar Evers; Malcolm X; and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. — and the role of the three in fighting American racism and the price each ultimately paid.

Evers was the courageous civil rights activist and field secretary for the NAACP working to get Black students admitted to the University of Mississippi and for voting rights and registration; and, Malcolm X epitomized redemption, turning his life around during imprisonment to become the charismatic top spokesman for the Nation of Islam, later, when on his own, becoming a Pan-African leader who critiqued the roles of Western imperialism and capitalism in dividing and controlling African, debating at the Oxford Union, and organizing protests after the murder of Lumumba.

Dr. King was perhaps the most prominent voice during the civil rights struggle. He helped lead the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott, helped found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and led many non-violent resistance events in Birmingham, Alabama. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964.

The documentary is both about Baldwin and his remarkably fresh observations about American racism and about the three freedom-fighters who fell early.

Evers was only 37 when shot dead; Malcolm was only 39 when killed in 1965; and, Dr. King too was 39 when murdered.

Baldwin had embraced them equally even though they employed divergent approaches in the struggle. Evers and Dr. King were identified with non-violent resistance; Malcolm became remembered for declaring that Black people had the right to employ “any means necessary” to bring about their liberation.

(There was some convergence. While Dr. King’s speeches such as “I Have A Dream,” are widely promoted, towards the end of his life, he had become much more militant and critical of U.S. capitalism and imperialism. This is very clear in his speech “Why I Am Opposed To The War In Vietnam.” Malcolm, towards the end of his life, embraced a strategy of forming broader alliances).

The profound pain Baldwin felt after the deaths of Evers, Malcolm, and King — as told by Peck on behalf of Baldwin — allows us to revisit many of those struggles of the 1960s.

Throughout the film Baldwin also gets to discuss White fears and discomfort when it comes to independent-minded Black people. The re-assuring, “Tomming,” safe, emasculated Black man, a staple of many movies, was always preferred by Whites.

“I Am Not Your Negro” which has been nominated for an Oscar is a film of the 1960s for 2017; the era of Donald Trump.