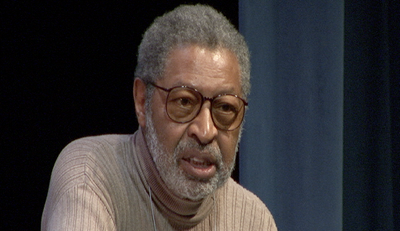

William Strickland at the 2013 Left Forum

[From The Archives]

College students were an integral part of the popular upheaval of the 1960s.

Beginning with the lunch counter sit-ins one month into the decade and continuing on through 1969 and beyond, college students around the country rallied to the cause of justice and freedom. The two best known student organizations of that time were the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and Students for a Democratic Society (SDS).

Another important group, though less well known, was the Northern Student Movement (NSM) and it was founded in Connecticut on the campus of Yale University.

Tens of thousands of young Americans were inspired by the lunch counter sit-ins that began in Greensboro, North Carolina and spread throughout the South. The lie that many knew was a lie — that the United States is based on freedom, justice and equality was exposed by the incredible bravery of young Black people. It was as though a dam had broken and a tidal wave of people, led by college students, were suddenly passionately committed to making the world a better place and not so concerned about forging comfortable careers for themselves.

Students at Yale University were no exception and some of them got together in the Fall of 1961 to form the NSM. One of the two projects they initiated was support of SNCC, which by then had branched out from the lunch counter sit-ins to spearheading the Freedom Rides, a concerted effort to end segregation and discrimination on the nations bus and train systems.

The other project the NSM undertook was to challenge racial discrimination in the North. To that end, the group organized an action a month after it was formed with the New Haven chapter of the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE) to protest local housing discrimination.

Like SNCC, the NSM had struck a chord and there were soon dozens of chapters on campuses throughout the Northeast. Initially, its membership was primarily White, though it worked closely with organizations like CORE whose memberships were mainly or exclusively Black. Within several years, NSM had recruited a large number of Blacks from both college campuses and from the communities where it established programs. NSM also began publishing a publication, Freedom North, with articles about its work and that of the Black Freedom Movement as a whole.

Peter Countryman, a Yale undergraduate from Chicago, was elected as the groups first executive director. Only 19 at the time, Countryman had already been active in civil rights work through the New England Student Christian Movement. He was instrumental in establishing a tutoring program in which students and recent graduates from Yale and other local colleges worked with young people enrolled in New Havens public schools.

The effort proved a success and NSM established similar programs in several dozen cities in the Northeast. By 1963, the group had enlisted over 2,000 students from a number of colleges to tutor an estimated 3,500 children. Countryman eventually left New Haven to spearhead NSMs tutoring program in Philadelphia.

In June of 1963, NSM members primarily from Trinity College established a tutorial program in Hartford with a staff of 25 and over 200 volunteers. The tutoring sessions were held in churches and other public facilities in or near the communities where the tutees lived and were so popular that the Hartford chapter grew to be one of the NSMs largest. Soon the group was holding classes on Black history and the arts and regular forums on police brutality and civil rights activities in the South. The NSM publicized these activities and news of the Freedom Movement through a newspaper, the North End Voice, which members distributed throughout Hartford. Simultaneously, NSM members in Hartford established the North End Community Action Project (NECAP) that organized sit-ins and other protests against discriminatory hiring practices around the city.

As the Freedom Rides continued through 1962 and into 1963, NSM members from college campuses in Connecticut traveled to the South to participate. They were also actively involved in a voter registration drive that SNCC launched in Mississippi in 1963 as well as, a year later, in Freedom Summer. One who participated in voter registration, Yale graduate student Bruce Payne, was shot and wounded in Mississippi by opponents of the campaign.

More students from Yale took part in these projects than from any other school and Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. was among many who took note. King visited Yale several times during this period including once at the invitation of Yales chaplain William Sloane Coffin, a supporter of the NSM who a few years late became one of the leading figures in the movement against US aggression in Southeast Asia. After one of his visits, King wrote to Coffin of the work being led by the NSM that he was really heartened by the movement in the right direction I sense at Yale.

In addition to New Haven and Hartford, the NSM had vibrant chapters on many campuses and in many cities, including New York, Detroit and Philadelphia. In 1963, the group moved its main office from New Haven to New York City and Peter Countryman was succeeded as executive director by William Strickland, an African-American graduate of Harvard who joined the NSM in his native Boston. After Freedom Summer, the group, while continuing to steadfastly support SNCCs work in the South, shifted more of its attention to the problems of Blacks in the North.

By 1965, many in the NSM had grown critical of what they saw as the limitations of a movement predicated on civil rights. Blacks in the organization, like Blacks in SNCC and the soon-to-emerge Black Panther Party, heeded the call of Malcolm X for Black self-determination, a broader and more revolutionary demand than civil rights.

They began to see themselves, in addition to being a part of a movement for Black liberation within the borders of the United States, as part of a global upsurge of primarily people of color against colonialism and imperialism. They began to call for Black Power and saw the need to transform the NSM and SNCC into all-Black groups to better achieve that goal.

Advocates of Black Power recognized the accomplishments and dedication of White members while stating that it was for Blacks to determine what their communities needed. Rather than providing services like the tutoring programs that were decided by and initiated by Whites, Whites were asked to leave the NSM and SNCC and challenged to organize the broader White community to support Black liberation.

Much as happened on a larger scale in SNCC, there were tensions around these changes within the NSM. Close friendships ended and there was anger and resentment in some quarters. Though understandable, the bitterness that some Whites felt was in large part a reflection of a movement that was still very young and somewhat immature. Race, after all, is perhaps the most complicated question confronting those of all colors dedicated to building a just society. For Whites, it is essential to understand that it is for Black people to decide what is best for Black people.

Blacks, especially Blacks from the poorer and working classes, and not Whites, must be in leadership of the Black Freedom Movement and significantly represented in the leadership of whatever larger multi-racial movement we are able to build.

Theres nothing easy about this, either in theory or practice. It was, and is, especially difficult for young Whites from schools like Yale to learn and accept. Many have, after all, been taught all their lives that it is their destiny and their right to rule. Without disregarding the pain some people experienced, the move by the NSM and SNCC to Black self-determination was a necessary one.

The NSM continued to do important work for most of the rest of the 1960s, organizing students and non-students alike. Many joined the much-larger SNCC, which by 1966 was establishing itself in the North. Others, upon leaving campuses, joined the Black Panthers, including in one-time NSM strongholds Hartford and New Haven, as well as Bridgeport.

As U.S. aggression in Indochina escalated and the movement against it exploded, many Whites who had been in the NSM immersed themselves in anti-war work. That effort was important, necessary and, in the end, successful, though in many ways that fact has been whitewashed from history.

Perhaps ironically, though, the massive growth of the anti-war movement in the late 1960s diverted Whites from taking up the challenge of their Black comrades in NSM to organize the greater White community to support Black liberation. Though we are on higher ground than 50 years ago, that challenge remains.

Bridgeport native Andy Piascik is a long-time activist and award-winning author who writes for Counterpunch, Z, and many other publications and websites.