By Mohammed Nurhussein

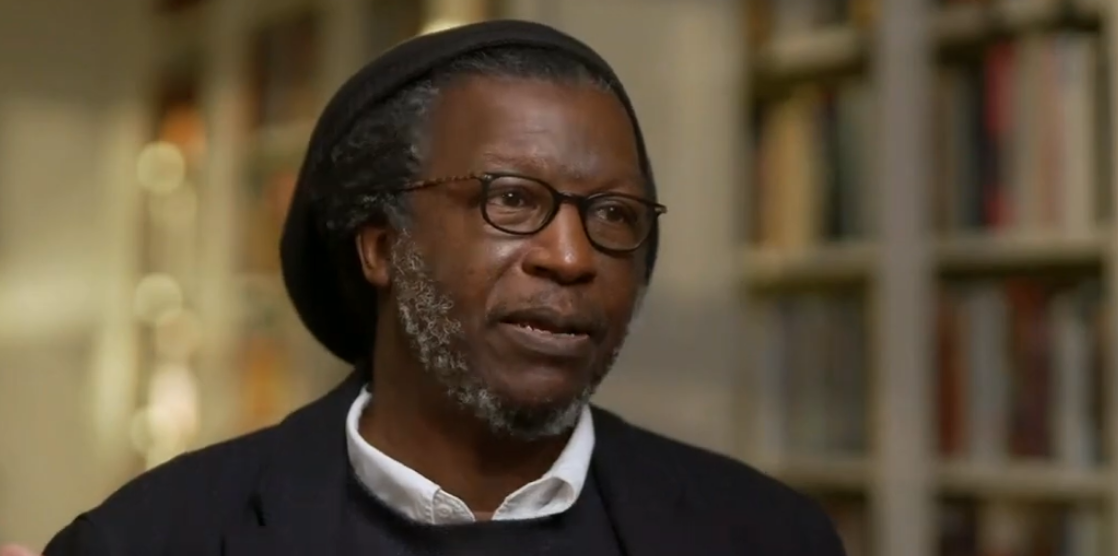

Photos: YouTube Screenshot\Mohammed Nurhussein

The following is from a presentation at an event celebrating the distinguished career and a life of service of Dr. Bereket Habte Selassie (seen below second from right) at UNC Chapel Hill NC conference on May 30, 2025.

Introduction

Dr. Bereket Habte Selassie’s life is a testament to resilience, intellectual curiosity, and an unwavering commitment to justice; a larger than life figure whose footprints on the contemporary history of Ethiopia, Eritrea and the Continent of Africa are indelible.

Where does one begin to describe an icon who has been, by destiny, a witness, a participant and protagonist, in some of the most pivotal and consequential events of 20th Century Africa.

Should I focus on the youngest Ethiopian attorney general in imperial Ethiopia, the brilliant constitutional lawyer and educator, the clandestine political activist, or the Eritrean freedom fighter and diplomat. Alternatively, I may choose to focus on the literary persona, encompassing roles such as novelist, essayist, memoirist, playwright, poet, and historian. Any attempt to capture the many dimensions of this historic figure would merely scratch the surface.

The Bard on Stratford-on-Avon once said, “Discretion is the better part of valor.”

Recognizing my limitations, I chose a less audacious undertaking: to write from the perspective of over half a century of friendship. Even here, I run into a conundrum. Do I write as an admirer who sees this man as a role model, mentor, and older brother, or as someone who has had the privilege of knowing him personally through the bond of close friendship?

Fortunately for me, I was assigned to focus only on his contributions to Ethiopia which itself is a formidable task.

Bereket’s formative years were shaped by a value-driven upbringing. He describes his father, Queshi Habte-Selassie and I quote “A man who shaped the course of my life”.

A particularly poignant moment occurred when his father, a protestant pastor, responding to the call of a muezzin stopped walking and turned to his son at the end of the adhan and said, “Bereket weddei (my son), we may have different names and ways of worshipping Him, but it is the same God we all pray to” thus teaching young Bereket about inclusiveness, interfaith harmony, and respect for the other. These principles became the cornerstone of Bereket’s philosophy and guided his future endeavors in justice and peaceful coexistence.

His father also saw to it that Bereket learns Ge’ez, the ancient Abyssinian language now extinct, used only in Orthodox Christian liturgy. Bereket is one of the few people I know who can speak and write in this ancient language.

Tale of the Two Selassies: Habte-and Haile–

What follows is a tale of two Selassies, a glimpse into Bereket Habte Selassie’s illustrious career in Emperor Haile Selassie’s Ethiopia.

He graduated at the top of his class from the elite Wingate high school in Addis Ababa and received an award from Emperor Haile Selassie and a scholarship grant to pursue higher education in Great Britain.

Armed with a law degree from the university of London, he returned to Addis Ababa and was received by the emperor at his palace. He was appointed inspector general in the ministry of justice.

This was the beginning of a career that was to plunge Bereket into the byzantine world of palace politics, first as inspector general, then an adjunct supreme court justice, and later as attorney general in quick succession. The latter position often brought him at odds with the emperor as he tried to reconcile the absolute authority and unquestioned power of a monarch with the principle of equality before the law.

In his memoir, Bereket describes the ministry of justice as a “dense forest of old rules and archaic procedures.” The ministry was run for the most part, by church schooled debteras whom he describes as, and I quote “masters of obscurantist thought and obfuscation”.

The vice minister instructed him to gain a comprehensive understanding of the ministry, document his observations and compile a detailed report outlining his findings and recommendations for reform. The report, completed in record time, reached the emperor who must have been pleased.

Emperor Haile Selassie was a deeply conflicted person. While it is true that he wanted to modernize the government, the reforms would often clash with the prerogatives of his imperial authority. He looked at these educated men with suspicion, afraid that ideas about human rights, the law and democracy may get into their heads. Some like Dr. Bereket ran afoul of His Imperial Majesty on multiple occasions but the emperor also appreciated the quality of work he was getting from him.

Pan Africanism

What is often overlooked is Bereket’s service to Ethiopia in promoting Pan Africanism.

He is a link between the early pioneers, such as Dubois and Garvey, and their successors like Nkrumah, Nyerere, and Sekou Toure.

During his student years in London and Paris in the late 1940s and early 1950s, he formed enduring friendships with fellow African students from both Anglophone and Francophone regions, facilitated by his fluency in English and French. These friendships were driven by their shared interest in Pan Africanism and the liberation of Africa.

In 1958, he represented Ethiopia at the All-African Peoples’ Conference organized by Kwame Nkrumah and George Padmore to hasten the pace of decolonization and the creation of the United States of Africa. Attendees included liberation leaders such as the Kenyan Tom Mboya, who was later assassinated, and Cameroon’s Felix Moumie, killed by French secret agents in 1960. Other notable participants were Frantz Fanon representing Algeria’s FLN, Abdulrahman Babu of Zanzibar and Patrice Lumumba of Congo, brutally murdered in 1961by the Belgian security services and the CIA.

Role in the establishment of the OAU

. For me however, it is his role in the drama surrounding the establishment of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) that fascinates me.

Most leaders of the newly liberated African states ignored Nkrumah’s call for immediate unification. Progressive pan-African leaders favoring unification formed the Casablanca group, while conservative pro-western leaders countered with the Monrovia group, advocating for a gradual approach.

In 1963, Emperor Haile Selassie convened a meeting in Addis Ababa to reconcile these competing visions, leading to the founding of the Organization of African Unity. Leaders from across Africa arrived including the towering figure of Gamal Abdel Nasser, drawing thousands to greet him at the airport as narrated by Bereket.

The debate at the meeting was intense, dramatic and polarizing. Nkrumah walked out in frustration, threatening to leave.

Here is when emperor Haile Selassie’s genius came into play. He knew the tight bond that existed between Nkrumah and Sekou Toure. Recognizing the respect accorded the elderly in African culture, the emperor played the father figure. Bereket recalls in his memoir how the emperor approached Sekou Toure and said “mon fils, je vous prie (my son, I implore you) asking him to bring back his brother. Sekou Toure responded as an African son would, “oui, mon pere, je vais essayer” (yes father, I will try). Sekou Toure brought Nkrumah back. There was thunderous applause in the hall. Thus, the OAU came to see the light of day.

Bereket, in the Ethiopian delegation had a hand in the drafting of the OAU charter as a member of the drafting committee.

Political Turmoil and Exile

The late 1960s and early 1970s represented a period of seismic political transformation in Ethiopia, marked by student activism and widespread discontent with the monarchy.

Concerned about Dr. Bereket’s impact on university students, the emperor exiled him to Harar in 1967 to serve as the provincial governor’s legal advisor and mayor of the city of Harar. At their first encounter, the governor made it clear to Bereket that his appointment was in fact a banishment and he was not going to see anyone or travel anywhere without the knowledge of the authorities. Over time, the governor and Bereket developed a respectful and cordial relationship.

Face to Face with a Legend in Harar, Ethiopia 1968

My story with Dr Bereket begins in late1968. Fresh out of medical school, and one of the first Ethiopian military doctors, I was posted to the 3rd Army Division hospital in Harar. I knew no one then except for a handful of my fellow officers, former classmates of the Harar Military Academy.

I was introduced to this, by now a legendary figure whose reputation as a progressive attorney general and law scholar was widespread among the University students at Haile Selassie University where he lectured on law, constitution and government.

Many of his former students attest to his substantial impact on their intellectual and professional development, as well as his influence in shaping their political views and activism.

Bereket and I began to meet after work at the Ras café on a regular basis. We quickly found that our views of the prevailing situation were in accordance with each other.

Sometimes I saw Bereket with his friend, a retired high-ranking police officer of British administered Eritrea. The gentleman always spoke to me in Amharic, careful with his words during those politically sensitive times, as he mistakenly believed I was an Amhara.

Permit me to digress a bit here to narrate an incident that I thought was hilarious. As the three of us met at the café, Bereket spoke to me in Tigrinya, and I responded in kind. The Eritrean gentleman, visibly bewildered, leaned over to Bereket and whispered “anta iziom natna diyom” meaning is he one of ours? Bereket and I burst out with laughter.

The Ras Cafe in those days was akin to Rick’s café in the movie Casablanca. Drawn by the increasing student unrest, the tension on the Ethio-Somali border and the ever-escalating war against Eritrean liberation fighters, one was likely to find agents of the emperor’s military and police intelligence, British and American ‘journalists’ doubling as CIA agents and the ‘nech lebash’, plain clothes spies of the government all rubbing shoulders at the hotel lobby. We were aware of all this as we met every evening, joined by our friend, Yohannes Admassu, the militant Marxist revolutionary poet who was teaching linguistics at the nearby Alemaya College.

Our discussions with Yohannes Admassu understandably gravitated to the raging student unrest at the Addis Ababa university now spilling over to the high schools in the provinces. The liberation struggle in Eritrea is another topic that often animated our discourse. We used to update each other about the developments in the city, in the schools, and in the military, each one of us sharing our assessment of the mood and sentiment in those institutions.

Security officials in Harar were spreading rumors that Bereket was behind the student unrest, that he was a communist, and supporter of the Eritrean rebels, thus putting his life in danger. Bereket had to always carry a piece for his own protection.

Living in the military camp as an army officer, I felt relatively safe, but my friends, Bereket and Yohannes Admassu were constantly subjected to periodic raids on their homes by the police.

Bereket back in Addis

Bereket was called back to Addis in 1970 to serve as a legal advisor to the influential minister of Interior. He soon left Addis for personal reasons detailed in his memoir. He found employment as legal counsel for the World Bank in Washington DC. Events in Addis were rapidly developing and Bereket was soon to find himself back in Addis in 1974

Bereket amid a maelstrom

Representatives from the police, army, air force, and territorial army were gathered in Addis to form a committee to discuss their grievances. The committee soon evolved into the Coordinating Committee known as the Derg. Expressing loyalty to the emperor, they demanded salary increases and improvements in living conditions. They also sought the emperor’s approval to apprehend officials in his cabinet responsible for the famine. The emperor agreed to the soldiers’ escalating demands until he was left isolated in his palace. The coup de grace occurred in early 1974 when a delegation of junior officers and other ranks came to the palace to read him a proclamation by which he was dethroned. He was taken away in a VW Beetle to be detained at the 4th Army HQ in Addis Ababa where the Derg had its offices. These series of events over several months came to be known as the creeping coup.

The samizdat ‘Democracia’ clandestinely published by Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Party gained popularity in the city, influencing an increasingly radicalized public. Even government newspapers started offering muted criticisms of the feudal monarchy. For a few months in 1974, it felt like a political awakening, our Prague Spring, if you will. The Derg, sensing power within its grasp, called back the popular General Aman Andom from retirement to serve as their chairman.

General Aman in turn reached out to his friend, Dr Bereket, to return to Addis as his special advisor to help him navigate the complex political and legal challenges and opportunities presented by the volatile situation. Bereket found himself involved in a rapidly developing political scenario that was to determine the future course of the emerging republic.

Commission of Inquiry

The Derg established a commission of inquiry to investigate the abuse of power of the royal regime and to determine responsibility for the devastating famine. Dr. Bereket was among the prominent members of the commission. Cabinet officials and members of the royal family were summoned to face the commission. The proceedings were broadcast live. Dr. Bereket’s incisive questioning of the witnesses and the revelations that emerged captivated the nation, making his name well known among the wider public.

The Derg was eager to conclude the investigations swiftly, perhaps worried about the Commission’s popularity. Growing impatient, they called upon the commission members to explain the reasons for the delay. Members of the commission, including the chairman, provided cautious responses. It was Dr. Bereket who articulated the legal issues regarding due process and highlighted the inadequacies of the old penal code, which did not encompass the crimes under investigation. He emphasized the need to develop a new penal code to effectively address these issues.

The Derg in the meantime was looking for a progressive new Prime Minister, first considered Ato Haddis Alemayehu, then Dr Bereket Habte-Selassie. However, Capt. Sissay of the Derg leadership convinced his comrades to reject Bereket due to his Eritrean background, which could upset their Amhara constituency.

The General and the Young Turks

It did not take long before tensions between the charismatic general and the amorphous 108-member Derg began to surface on policy, power sharing, rule of law and a plethora of issues most notably, the vexing problem of the war in Eritrea. Things came to a head resulting in a shootout at general Aman’s residence where the general lost his life. The same day the Derg ordered the 60 detainees summarily shot. Everything changed after the massacre, hopes for a peaceful transition dashed.

The hunt was on for Dr. Berket, General Aman’s special advisor. His escape from Addis Ababa to Eritrea through Tigray eluding the nationwide dragnet for his capture is described in his celebrated memoir “The Crown and the Pen “and reads like a thriller.

The next chapter in his distinguished career was to begin in Eritrea as a freedom fighter and law giver and will be presented by scholars better equipped and more knowledgeable than I am.

Dr. Bereket, right, shown with Ambassador Sidique Wai.

Conclusion

Bereket Habte Selassie remains a beacon of hope and a symbol of Africa’s indomitable spirit. His contributions to justice, good governance, human rights, and intellectual thought have left an everlasting legacy. Whether navigating the corridors of power or the halls of academia, his story is an inspiration for generations to come, ensuring his place as one of Africa’s true Renaissance figures. He is a man for all seasons.

The author of this column, Dr. Nurhussein (below) enjoys a meal. Nurhussein is a retired Ethiopian-born medical doctor and author of the memoir “Made In Ethiopia.”