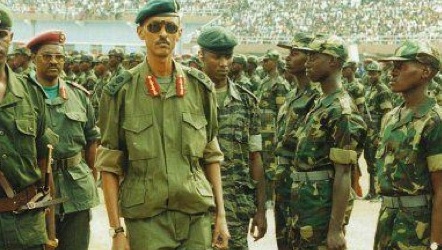

Gen. Kagame; his portrayal as a savior was elaborate fiction

[Books]

From Tragedy to Useful Imperial Fiction

Robin Philpot’s important new book Rwanda and the New Scramble for Africa is an eye-opener and essential reading for anybody who wants to understand the recent history of Rwanda, ongoing U.S. and Western policy in Africa, and how efficiently the Western propaganda system works.

As in the case of the wars dismantling Yugoslavia, there is a “standard model” of what happened in Rwanda both in 1994 and in the preceding and later years, a model that puts the victorious Tutsi expatriate and Ugandan official Paul Kagame, his Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF), and his Western supporters in a favorable light and the government of Rwanda, led by the Hutu Juvenal Habyarimana, in a negative light. Philpot challenges this model in all of its aspects and shows convincingly that, in a virtual miracle of systematic distortion, this version of history stands the truth on its head.

One important feature of the standard model is its portrayal of the West as a regrettably late intervener in the Rwanda struggle, with oft-cited ex-post apologies from Bill Clinton and Madeleine Albright during their visits to Rwanda in 1997 and 1998 for U.S. and allied failure to intervene to prevent the massive killings in 1994.

Demolishing this distortion of history, Philpot shows that U.S. and Western intervention in Rwanda was crucial both in preparing the ground for the 1994 bloodbath and in the failure to stop it after it was well underway. The United States and Britain saw to it that UN peacekeeping forces were smaller in 1994 than had been agreed to in the 1993 Arusha Peace Accords and that they were cut sharply in February and then in April 1994 when killings were raging. The Rwanda government called repeatedly for a ceasefire, but the United States was supporting Kagame’s and the RPF’s conquest of Rwanda and, with a Kagame victory in sight, the U.S. intervention at that point was to protect the RPF killing machine from any outside interference. Philpot quotes former UN Secretary-General Boutros Boutros- Ghali’s repeated assertion that, “The genocide in Rwanda was one hundred percent the responsibility of the Americans.”

Philpot traces U.S. support of Kagame and the RPF back to the October 1990 invasion of Rwanda from Uganda and even earlier. Kagame had trained at Ft. Leavenworth and the United States and its allies were already supplying Uganda with arms, training, and diplomatic support in 1990. The invasion and occupation of Northern Rwanda by this foreign-based force, which started on October 1, 1990, resulted in the forced exodus of hundreds of thousands of Hutu farmers. Although this was a violation of the UN Charter, as well as a major human rights disaster, it led to no condemnation or action by the UN or “international community.”

In fact, in succeeding years the United States and its allies supported the penetration of the RPF into the political and military structures of Rwanda, essentially pushing a major subversive force into the institutions of a victim of aggression. The Rwanda government was also forced by the IMF and World Bank, along with the United States and its allies, to abandon its social democratic policies, disabling it as a force helping ordinary citizens, including both the many refugees dislodged by the RPF and the large numbers streaming into Rwanda from Burundi where a Tutsi-military coup d’etat and murder of its Hutu president in October 1993 had led to a flight similar to that produced by Kagame and the RPF within Rwanda itself.

Philpot cites evidence that as early as 1990 the RPF organized covert cells throughout the country, surely designed for future action in a plan to seize control of the state.

Tutsis comprised at most 15 percent of the population and, given their historic role as a ruling superior class—defeated in a 1959 social revolution with many fleeing to Uganda—and their role via the RPF in ethnic cleansing and refugee creation from 1990 onward, there was no chance that they could take power in a free election. Philpot makes a compelling case that they knew this quite well and were planning a violent takeover, which did in fact occur.

Philpot stresses that from October 1, 1990 onward and through the mass killings years of 1994-1995, Rwanda suffered a de facto war, carried out by the RPF, with Ugandan help, and, more crucially, with the assistance of the United States and its close allies. This also meant the automatic help of the subservient UN. In the standard model there was no war—the 1990 invasion and its consequences are kept out of sight and so is the steady infiltration and major-war preparations of the RPF up to the onset of a full-scale war and mass killings in April 1994 and onward.

The large-scale slaughter in Rwanda began immediately after the shooting down of a plane carrying Rwanda President Juvenal Habyarimana and Burundi president Cyprien Ntaryamira at the Kigali airport on April 6, 1994. This was widely recognized as the “triggering event” in the mass killings and “genocide.” In the standard model, the deaths of Habyarimana and Ntaryamira were either organized by Hutu government officials or were inexplicable. However, there is overwhelming evidence that these deaths were organized by Paul Kagame and the RPF, very possibly with the help of their Western supporters.

The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) looked into this issue in 1996 and 1997, with their principal investigator Michael Hourigan eventually charging the crime to Kagame and the RPF. French and Spanish investigators came up with the same result. But when Hourigan presented his report to ICTR prosecutor Louise Arbour, after consulting with U.S. officials Arbour closed down the investigation and it has not been taken up since by the ICTR or any other international organization despite the importance of this event to the terrible and much publicized devastation that ensued.

To continue the review please see Global Research