Author: Jamal Mtshali

[Book Excerpt]

Book: “Last in Line: An American Destiny Deferred”

Chapter: From “Get Over It”

Before America Ate Up Trump’s Rhetoric…

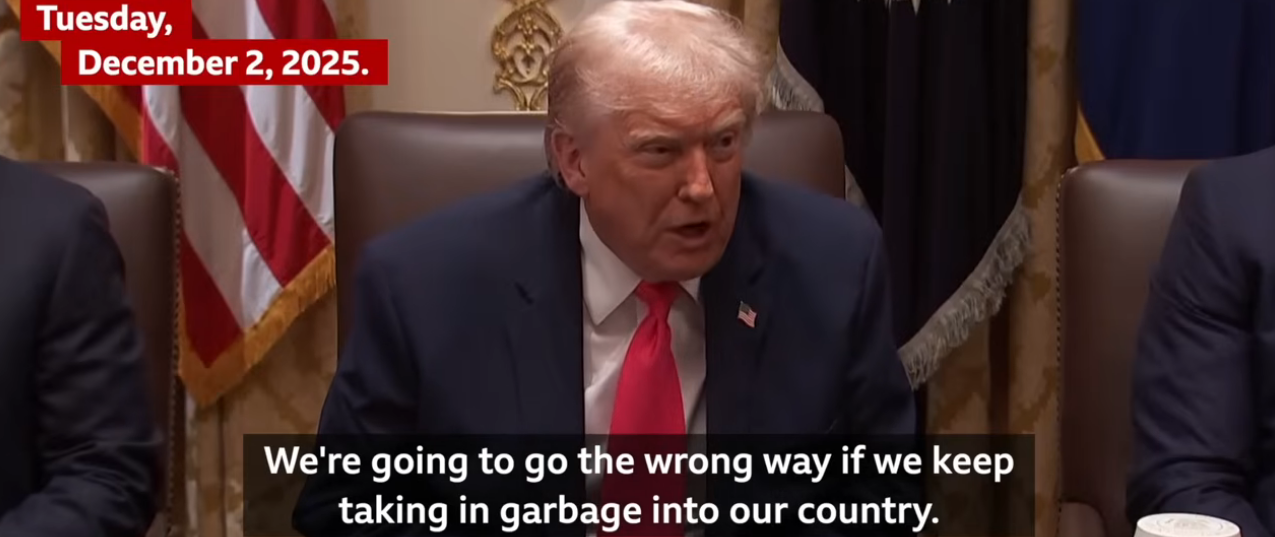

Before America ate up Trump’s rhetoric, it ate up “Pound Cake.” On January 20, Donald Trump was inaugurated as the 45th President of the United States. Eight years ago, Barack Obama owed his ascent to retreat from incendiary rhetoric—that of his former pastor, Reverend Jeremiah Wright. Trump has razed that road en route to the rebirth of a nation, spewing fiery rhetoric at numerous groups: women, Muslims, the disabled, and of course African Americans. Although a barrage of sexual assault allegations suggested behavior to match such impassive rhetoric, Trump’s resounding November 8 victory reaffirmed Middle America’s dismissive stance on issues of race and gender.

Back in 2004, Bill Cosby’s infamous “Pound Cake” speech drew rapturous applause from what is now Trump’s America, which praised Cosby and welcomed him as a liberal myth-busting harbinger of truth. That is until numerous women, most white, accused Cosby of sexual assault. “Pound Cake” won Cosby some brownie points, but not enough.

Cosby’s demise was well-deserved. His sycophancy did not furnish the immunity which not only enabled Trump to avoid punishment and unequivocal public censure, but allowed his ascent into the Oval Office. Middle America’s starkly different responses to Cosby and Trump reveals a great deal about the ways in which rhetorical power interacts with race and gender on behalf of the status quo.

“Pound Cake” forever altered Cliff Huxtable’s palatable image. Its recipe called for one heaping tablespoon of indignation. Bill Cosby had not been known for stridence—or any significant political or social commentary, really. Jell-O? Cardigans? Sexual assault? Sure. Each of these things figured in the schema associated with Cosby. (In all fairness, the third only became a synonym for “Cosby” a decade later.) But Cosby’s “Pound Cake” speech was a different jingle—less gelatinous yet more appetizing to America’s insulin-resistant masses. America devoured. Cosby’s criticisms of the black community’s gross imperfections and shortcomings were lauded by many, perhaps effusively so by mainstream America.

Cosby arraigned the usual suspects: negligent and absent black fathers; insolent, truant, rambunctious, gang-banging adolescent black males; and irresponsible, ever-pregnant teenage black women. In a harangue of the black “lower” income brackets that elicited scarce smiles from the stone-cold faces of Middle America, Cosby cast stones in a paternalistic back-in-my-day fashion that left much of the nation nodding. Cosby didn’t even spare rod-shy single black mothers, inquiring of their orange jumpsuit-donning sons, “Where were you when he was two…twelve…eighteen? Why didn’t you know he had a pistol?”

Of course, all this was before Cosby again reintroduced himself to the American public as a prolific dispenser of Quaaludes—and probable rapist, to boot. Cosby came to the NAACP’s 50th anniversary celebration of the 1954 Brown v. Board ruling equipped with statistics, attesting to the “50 percent [high school] dropout rate” among black students as well as a similarly credible claim of the commonality of black women having babies by “five or six different men.” Cosby also bore anecdotal testimony of young black males getting “shot in the head over…pound cake!” by police officers whose lethal judgment we shouldn’t dare question. Why? “What the hell was he doing with the pound cake in his hand?” His thoughtful analysis assumed an interestingly xenophobic slant, insisting that in its misguided, ignorant, linguistically inept African American youth, America was breeding its own “ingrown immigrants” who like to “shoot…and do stupid things” for kicks.

Black America’s dysfunction is often said to result from its imprudent use of a broken moral compass. This explains the misdirection of irresponsible, marijuana-smoking, baby-making, school-quitting (and, according to Bill, pound cake-stealing) black teenagers, as well as criminal, sex-crazed, malingering adult black men (not to mention the tax dollar-embezzling black women for whom conception is a fiscal matter).

In spite of such perspicacity, Cosby’s remarks were not without detractors. Many in the black community rebuked Cosby for his hyperbolic, extended lamentation, accusing him of spewing fabricated anecdotes in the vein of Ronald Reagan’s “welfare queen” fables and neglecting systemic racism’s role in engendering many of the ills to which he colorfully alluded. To them, Cosby did nothing productive except add to the black stereotype repertoire—that of the hungry black male who risks his life and those of others for to-die-for—literally—cakes and pizzas. Perhaps killing over fruits and salads would, to Mr. Cosby, be a more salubrious, forgivable pathology (not to mention something we could never conceive of Fat Albert doing).

Michael Eric Dyson issued a pointed rebuttal to Cosby’s comments entitled Is Bill Cosby Right? Dyson argued that Cosby’s deprecations were shortsighted and accused Cosby of shifting the blame too far from the problem of institutional racism, insisting, “All the right behavior in the world won’t create better jobs with more pay,” and adding, “…if the rigidly segregated educational system continues to miserably fail poor blacks by failing to prepare their children for the world of work, then admonitions to ‘stay in school’ may ring hollow.” Contrarily, conservative pundit Bill O’Reilly commended Cosby, stating that he was preaching “self-reliance” and that those in contention with Cosby were making “excuses.”

Cosby’s cognitive dissonance with regard to racism—a more direct and explicit problem during his youth—is rather stunning. His nostalgia over the seeming cultural coherence of his era is unbridled. He adds that African Americans back in his day, “[Knew it was] important to speak English,” at least when not hanging out on the street corner. Cosby evokes shame in lackadaisical and imprudent black youth, reminding them of the stalwart blacks of his day who were showered in “rocks” and “firehoses” for such opportunities which their posterity now squandered. Cosby’s statements corroborated what much of America wanted to proclaim but was often afraid to.

Cosby’s publicized corroboration of such attitudes lent an enlivening air of legitimacy. It’s one thing for someone white (including white millennials, who prove no exception) to proclaim such beliefs. But for a famous, respected black man to qualify sentiments ubiquitous in white America was vindicating. White America praised Cosby—“Finally, one of them’s got it figured out!

Where does mainstream America’s perception of a black America in dire need of calibration come from? Is it procured from nightly newscasts? Reality series on VH1 or Black Entertainment Television? Are Americans confusing the subject matter of fictional television shows and movies with real life? Perhaps there is a sounder, empirical basis. Perhaps researchers are bivouacking in housing projects, recording observations of the rough and wild African American habitat. Clearly, there is some sort of intimacy that gives mainstream America license to profess certain and legitimate understanding of just what black America is really like. Whatever the method of research, white America is quite confident in the conclusions it draws from it.

Gallup polls from 1962 and 1963 indicated that the overwhelming majority whites thought blacks received equal treatment with regard to opportunities for jobs, schooling, and housing. Needless to say, these sentiments were contradicted by the national conflagration that erupted in response to the question of whether blacks deserved equal rights in America. That such attitudes were pervasive in the early ’60s seems preposterous. As for today, we feel we have arrived. Racial prejudice has been erased, a black president has been elected, and Dr. King’s dream has at last come to fruition. Racism is a documentary, a history term paper, a museum exhibit. But to speak of racism in a modern context? That’s beating a beast slayed long ago.

Except that beast has not been slayed; we know this by our reflection. Racism is not a tired topic—racism is itself tired. The ability to grasp this distinction separates Americans like Bill Cosby and Donald Trump from Americans who get that race is a neglected blight on America’s moral legacy. The sound research conducted by the Cosby crowd has convinced them that racism lives only in imagination, an extinct Easter Bunny poached by a suddenly race-blind America in the 1960s only to be resurrected by a modern, attention-seeking, race-baiting element.

“Pound Cake” proved one thing: black sycophancy only buys so many brownie points. The bigger takeaway is that character matters, not skin color—a point that seems lost on Cosby, Donald Trump, and much of Middle America. As Trump settles into the White House, Americans still look forward to the day when racism exhales its last breath, living only in retrospective contexts. If America’s inaugural air is our forecast, that day remains distant.

Adapted from the chapter “Get Over It” in Jamal Mtshali’s “Last in Line: An American Destiny Deferred” published by African American Images and available on Amazon. For more on the author, visit www.JamalMtshali.com. Follow Jamal on Twitter at @jtmtshali.