[COVID-19\School Reopening]

Consumer Reports: “Fifty-seven percent of Black Americans and 52 percent of Hispanic Americans say they think that schools should remain closed and that children should begin the school year taking classes online, compared with 25 percent of whites.”

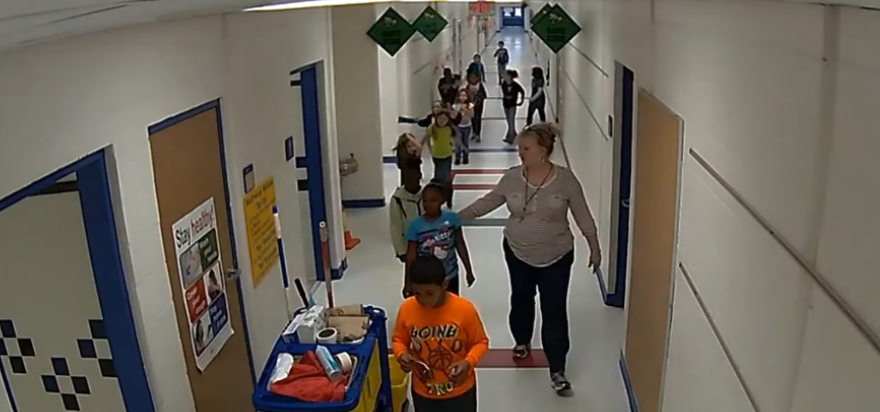

Photo: Consumer Reports

Survey: Blacks and Latinos twice as likely as whites to say schools should remain closed.

For Aundi Marie Moore, a Black mother of two in Bowie, Md., there’s no debate about whether her kids should be returning to school this year during the coronavirus pandemic. “My husband and I decided we’re not going to send our children to school, even if it’s mandated, until there’s a vaccine and the safety and health of our community is put first.” Moore says. “Right now, things just seem too rushed.”

Moore is not alone in her concern. Fifty-seven percent of Black Americans and 52 percent of Hispanic Americans say they think that schools should remain closed and that children should begin the school year taking classes online, compared with 25 percent of white Americans, according to a nationally representative survey of over 2,000 U.S. adults conducted by Consumer Reports in July.

The reasons for this disparity are no doubt complex. Still, CR found some common reasons emerge from interviews with Black and Hispanic parents who were not part of the survey. They include concerns over greater susceptibility to COVID-19, a lack of faith that safety protocols, including wearing masks and social distancing, can be followed and enforced in a school setting, and a feeling that the decision to open schools is inconsistent with other policies in place to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

Black and Hispanic communities have been hit especially hard by the pandemic. For instance, adjusted for age, the rate of COVID-19 deaths in the Black community is more than four times the rate in the white community. And a new study of children in Washington, D.C., showed that minorities and socioeconomically disadvantaged children are infected with COVID-19 at much higher rates than other children. In the study, Black children were more than four times as likely as white children to test positive for COVID-19, and Hispanic children were more than six times as likely as white children to test positive.

The concerns also are occurring amid a fierce debate about whether schools should reopen as COVID-19 cases rise in some areas. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has talked about the importance of reopening schools, but some school systems, such as Chicago’s public schools, are opting to start classes virtually.

“In essence, people’s opinions about whether or not schools should open are based on the data Black and Hispanic people have received,” says Mondi Kumbula-Fraser, director of the Black and Brown Coalition for Educational Equity and Excellence, in Montgomery County, Md. “The opinions people are expressing are based on fear: fear of infection and fear of death.”

Kumbula-Fraser gave the recent example of a Washington Post story in July that said 74 percent of new COVID-19 patients in Montgomery County were Hispanic. She adds that students in her county all will be studying remotely through the end of the year, so she doesn’t have to make the decision yet about her two children returning to in-classroom studies.

Medical Worries

Moore says that the disproportionate number of Black COVID-19 cases and deaths influenced her decision to keep her children home until there’s a vaccine and proven safety measures are in place. She says she’s relieved that the schools in her county will be online-only through at least the end of the year.

“Unfortunately, so many in the Black community have passed away from COVID-19,” she says. “It’s extremely dangerous to a lot of us because of underlying medical issues like diabetes and high blood pressure caused by choices we’ve made or that have been made for us over centuries. My son is extremely asthmatic, and I do not want him exposed to COVID-19.”

In addition to concern over poorer medical outcomes, Black parents CR spoke with expressed a lack of confidence that school policies would be effective in keeping their children safe.

The debate over whether children should return to physical classrooms is complicated by the sizable variation in COVID-19 infection rates across the country and the lack of any reliable treatment or approved vaccine. Some teachers unions are threatening to strike or sue if they’re required to return to classes without some concessions or assurances, such as more provided protective gear.

Further complicating the issue are concerns of some parents and child development experts who say keeping children out of the classroom could cause long-term social and academic harm. There are also economic consequences to keeping schools closed: Children studying from home can create a drain on family finances when one or both parents are unable to work remotely.

School Policies Too Vague

As a high school guidance counselor in Manhattan, Tara Williams, who is Black, has an insider’s view of how students interact and how schools are run. She says that she is being required to return to work when the school year begins but that her two school-age children will remain home and older family members will watch them.

“My kids are going to study remotely, at least for the first couple of months,” Williams says. “I want to see what happens before deciding if they can go back. To be honest, I don’t have faith in the system right now. Will the buildings be cleaned every night the way we’re being told they will? My kids are in elementary school, and they want to interact with other children. How are the schools going to make sure that kids keep their masks on and maintain distance?”

Tammie Reid, a Black mother of two school-aged children in Newark, N.J., who serves as the chair of a local charter school, says there’s a historic basis for this mistrust.

“Historically, when it comes to public systems, our people have been overrepresented when it comes to poor outcomes and underrepresented when it comes to better choices,” Reid says. “I would discern from the survey data that Black and Hispanic parents are reluctant to trust that the decisions being made are in the best interests of the children and families in their communities.”

Reid, who home-schools her children throughout the year, adds that the lack of a coherent government policy regarding COVID-19 could be adding to this distrust.

“The determination of readiness should be made in the context of the entire community,” she says. “To say that schools can open safely but other places that serve large populations, like gyms and restaurants, should remain closed is inconsistent.”

Learning Heroes, a nonprofit organization that supports parents in taking an active role in their children’s education, has been interviewing parents of public school children in three states and has found, in general, that white parents have more confidence than Black and Hispanic parents that schools can reopen safely.

“Purely anecdotally, we’re hearing that white parents are receiving ongoing communication from schools in a way that Black and Hispanic parents are not,” says Bibb Hubbard, the organization’s president and founder. “All of the parents we have interviewed are acutely aware of the lack of social interaction children face when studying at home, but white parents have a higher level of confidence that schools can open safely and that it’s worth the risk. Black and brown parents want to put safety first; for them it isn’t worth the risk.”

Multigenerational Risk

The Black and Hispanic parents CR spoke with also noted that families of color often live in households that include multiple generations living under the same roof or in close proximity, which also heightens concerns about children returning to school.

“Culturally, in Black and Hispanic families, there’s often a grandparent or an elder relative who lives with the family,” Reid says. “Those older folks are at higher risk for COVID-19, and I think there’s a greater awareness of the impact the infection could have.”

Joe Rojas, a business coach and Hispanic father of two in the New York City borough of Queens, says that he and his family have been carefully following safety protocols since the beginning of the pandemic and that this would no longer be possible if the children returned to school.

“I’m concerned that my kids aren’t socializing enough, but I’m more concerned about the people at the homestead, like my mother-in-law and an older neighbor who the kids see all the time,” he says. “When you put young kids in a classroom, you can’t really keep them apart.”

Black and Hispanic parents we spoke with acknowledged that keeping schools closed would create significant challenges, including, in many cases, having at least one parent remain home, potentially losing an income. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics says that less than 20 percent of Black employees can work remotely, while nearly 30 percent of white workers are able to do so.

But the parents said that it was a sacrifice many feel is worth making. “The Black and Latino families I know would rather not work and be poor than allow their family to be harmed,” Rojas says. “Family is more important than anything else. That’s it.”

Moore says that, while she cannot speak for all Black people, a focus on the family is common to Black values. “It will kill us more to see our child suffer from this preventable disease than to not be able to pay our bills. That’s important, too, but not more important than family.”

Williams, the guidance counselor, notes that socioeconomic status also likely influences opinions about whether schools should reopen.

“You’d be surprised at the kind of magic some people can pull out of their hat, I have to tell you,” she says. “Maybe some parents have a special bunker set up where they can douse the kids and clean them up as soon as they come home. But for Black and Latino families who don’t have a large home, where do you quarantine if someone gets sick? In your foyer? White people probably have more space or some sort of plan. But most of the Black and Hispanic people I know aren’t confident. There are too many what-ifs.”

By Kevin Doyle\Consumer Reports https://www.consumerreports.org/cro/index.htm