The 1918 Flu’s Effect on the 19th Amendment and Women’s Suffrage

“‘This new affliction is bringing sorrow into many suffrage homes and is presenting a serious new obstacle in our Referendum campaigns and in the Congressional and Senatorial campaigns,’ [Carrie Chapman Catt] continued [in a letter to supporters in 1918]. ‘We must therefore be prepared for failure.'”

“Suffragists had been fighting for women’s right to vote for 70 years, and victory seemed almost in reach. Even with the United States fully mobilized for World War I. President Woodrow Wilson had come out in support of a constitutional amendment, and the House of Representatives had passed it.

Then the Spanish flu struck, and the leaders of one of the longest-running political movements in the country’s history had to figure out how to continue their campaign in the midst of the deadliest pandemic in modern times.

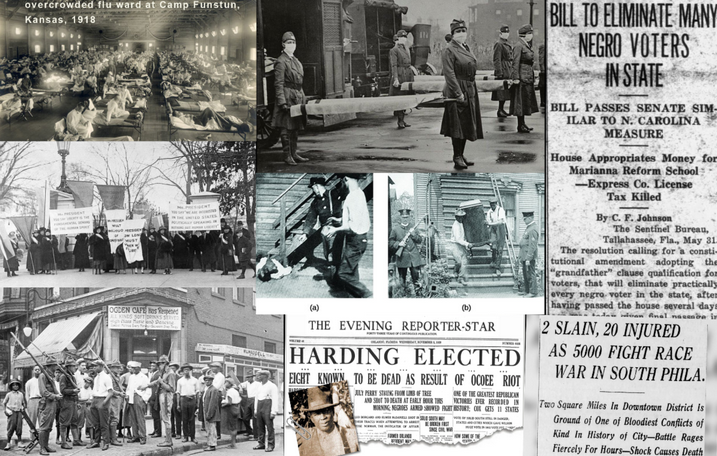

The first wave of the flu coursed through the country in the spring of 1918, ebbing by summertime. During that period, the Senate, dominated by southern Democrats determined to stop the enfranchisement of African-American women, was refusing to pass the bill to send the suffrage amendment to the states for ratification. Votes were announced twice, then canceled. By early fall, suffragists could see that they were two votes short of the necessary two-thirds for passage.

Finding those two senators was proving impossible. Maud Wood Park, the chief suffrage lobbyist, wrote to her husband that she felt ‘as if I were trying to swim in a whirlpool’ and that it was taking ‘every ounce of thought and energy in me.’ Something else needed to be done to break through.”

“But in September [1918] the flu came roaring back…[In response, The] U.S. Public Health Service issued a nationwide advisory to local health departments to prohibit large meetings and gatherings. Suffragists’ election campaigns were immediately compromised. Organizers had to postpone a train tour of previously arrested suffrage protestors, which had been expected to draw great crowds along its route from Washington, D.C., to Oregon. On the second floor of Suffrage House in the nation’s capital, Carrie Chapman Catt was “chained to her bed” by the flu. Nonetheless, she was determined to consult on strategy with a close ally of the president, Montana Senator John Walsh, but he too was stricken with the flu. Catt couldn’t come downstairs, and Walsh couldn’t go up, so an intermediary shuttled between them to conduct their confidential discussion.”

“Faced by bans on public gatherings, suffragists switched to the personal touch, reaching out directly to neighbors and friends. They emphasized their patriotism and quoted the president saying that votes for women was a proper reward for their wartime sacrifice. National headquarters provided more than a million pamphlets for distribution door to door and 300 weekly bulletins for placement in local newspapers. Women signed petitions urging male voters to pass the four states’ referendums.”

“More than anything, though, it was the extensive grassroots organizing suffragists had perfected that carried them through. They’d been laying the basis for their campaigns long before the influenza barreled in. Cities and towns in each state had their own organizations, linked to national strategy. Local women had developed sophisticated political skills. They knew how to identify opportunities and overcome obstacles—South Dakota and Michigan had already held several referendums. All that preparation was crucial.

The epidemic suppressed voter turnout, with three million fewer ballots cast than in the 1914 mid-term election. Nonetheless, the suffrage referendums in Michigan, South Dakota, and Oklahoma passed, each with a comfortable margin. Gratitude for the role women played during the war and now in the pandemic influenced the results. With so many physicians serving in the armed forces, nurses became the front line of care for the sick.

Only the Louisiana referendum failed. This was the first in the South, a region where women’s suffrage had been doomed by the overwhelming fear of African-American women voting. The state campaign, led by women who opposed national coordination and strategy, didn’t produce the energy, determination, and enthusiasm that brought victory elsewhere in the face of the flu crisis.”