By Transformative Justice Coalition

Photos: Video Screenshot\Wikimedia Commons

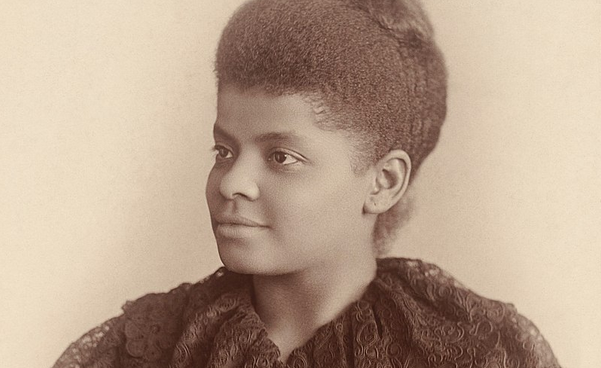

As Black History Month celebrations continue, today we honor Ida B. Wells-Barnett a journalist, civil rights activist, and suffragist who endlessly fought against racial and sexual discrimination.

Biography

“Born a slave in 1862, Ida Bell Wells was the oldest daughter of James and Lizzie Wells. The Wells family, as well as the rest of the slaves of the Confederate states, were decreed free by the Union, about six months after Ida’s birth, thanks to the Emancipation Proclamation.” “Although enslaved prior to the Civil War, her parents were able to support their seven children because her mother was a ‘famous’ cook and her father was a skilled carpenter.” “Ida B. Wells’s [sic] parents were active in the Republican Party during Reconstruction. Her father, James, was involved with the Freedman’s Aid Society and helped start Shaw University, a school for the newly freed slaves (now Rust College) and served on the first board of trustees.” “When Ida was only fourteen [though some sources say she was sixteen], a tragic epidemic of Yellow Fever swept through Holly Springs and killed her parents and youngest sibling. Emblematic of the righteousness, responsibility, and fortitude that characterized her life, she kept the family together by securing a job teaching [at only 14 years old]. She managed to continue her education by attending near-by Rust College.”

“In 1882, Wells moved with her sisters to Memphis, Tennessee, to live with an aunt. Her brothers found work as carpenter apprentices. For a time, Wells continued her education at Fisk University in Nashville.” “It was in Memphis where she first began to fight (literally) for racial and gender justice. In 1884 she was asked by the conductor of the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad Company to give up her seat on the train to a white man and ordered her into the smoking or ‘Jim Crow’ car, which was already crowded with other passengers. Despite the 1875 Civil Rights Act banning discrimination on the basis of race, creed, or color, in theaters, hotels, transports, and other public accommodations, several railroad companies defied this congressional mandate and racially segregated its passengers. It is important to realize that her defiant act was before Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the U.S. Supreme Court decision that established the fallacious doctrine of ‘separate but equal,’ which constitutionalized racial segregation. Wells wrote in her autobiography:

‘I refused, saying that the forward car [closest to the locomotive] was a smoker, and as I was in the ladies’ car, I proposed to stay. . . [The conductor] tried to drag me out of the seat, but the moment he caught hold of my arm I fastened my teeth in the back of his hand. I had braced my feet against the seat in front and was holding to the back, and as he had already been badly bitten he didn’t try it again by himself. He went forward and got the baggageman [sic] and another man to help him and of course they succeeded in dragging me out.’

Wells was forcefully removed from the train and the other passengers–all whites–applauded. When Wells returned to Memphis, she immediately hired an attorney to sue the railroad.” “Wells sued the railroad, winning a $500 settlement in a circuit court case. However, the decision was later overturned by the Tennessee Supreme Court.”

“Her suit against the railroad company also sparked her career as a journalist “and “led Ida B. Wells to pick up a pen to write about issues of race and politics in the South.” “Many papers wanted to hear about the experiences of the 25-year-old school teacher who stood up against white supremacy. Her writing career blossomed in papers geared to African American and Christian audiences.” “Using the moniker ‘Iola,’ a number of her articles were published in black newspapers and periodicals. Wells eventually became an owner of the Memphis Free Speech and Headlight, and, later, of the Free Speech.

While working as a journalist and publisher, Wells also held a position as a teacher in a segregated public school in Memphis. She became a vocal critic of the condition of blacks only schools in the city. In 1891, she was fired from her job for these attacks. She championed another cause after the murder of a friend and his two business associates.” (emphasis in original)

“In 1892 three of her friends were lynched. Thomas Moss, Calvin McDowell, and Henry Stewart. These three men were owners of People’s Grocery Company, and their small grocery had taken away customers from competing white businesses. A group of angry white men thought they would ‘eliminate’ the competition so they attacked People’s grocery, but the owners fought back, shooting one of the attackers. The owners of People’s Grocery were arrested, but a lynch-mob broke into the jail, dragged them away from town, and brutally murdered all three. Again, this atrocity galvanized her mettle. She wrote in The Free Speech:

‘The city of Memphis has demonstrated that neither character nor standing avails the Negro if he dares to protect himself against the white man or become his rival. There is nothing we can do about the lynching now, as we are out-numbered and without arms. The white mob could help itself to ammunition without pay, but the order is rigidly enforced against the selling of guns to Negroes. There is therefore only one thing left to do; save our money and leave a town which will neither protect our lives and property, nor give us a fair trial in the courts, but takes us out and murders us in cold blood when accused by white persons.’

Many people took the advice Wells penned in her paper and left town; other members of the Black community organized a boycott of white owned business to try to stem the terror of lynchings. Her newspaper office was destroyed as a result of the muckraking and investigative journalism she pursued after the killing of her three friends. She could not return to Memphis, so she moved to Chicago. She however continued her blistering journalistic attacks on Southern injustices”: “first as a staff writer for the New York Age”, “being especially active in investigating and exposing the fraudulent ‘reasons’ given to lynch Black men, which by now had become a common occurrence”; and, then, “as a lecturer and organizer of antilynching societies. She traveled to speak in a number of major U.S. cities and twice visited Great Britain for the cause. In 1895 she married Ferdinand L. Barnett, a Chicago lawyer, editor, and public official, and adopted the name Wells-Barnett. From that time she restricted her travels, but she was very active in Chicago affairs.” (emphasis in original)

“In 1896, [Ida] formed the National Association of Colored Women.” “The National Association of Colored Women Clubs (NACWC) was established in Washington, D.C., USA, by the merger in 1896 of the National Federation of Afro-American Women, the Women’s Era Club of Boston, and the National League of Colored Women of Washington, DC, as well as smaller organizations that had arisen from the African-American women’s club movement.

Founders of the NACWC included Harriet Tubman, Margaret Murray Washington, Frances E.W. Harper, Ida Bell Wells-Barnett, and Mary Church Terrell. Its two leading members were Josephine Ruffin and Mary Church Terrell. Their original intention was ‘to furnish evidence of the moral, mental and material progress made by people of color through the efforts of our women’. The NACW came about as a result of a letter written by James Jacks, the president of the Missouri Press Association, challenging the respectability of African American women, referring to them as thieves and prostitutes.

During the next ten years, the NACW became involved in campaigns in favor of women’s suffrage and against lynching and Jim Crow laws. They also led efforts to improve education, and care for both children and the elderly. By 1918, when the United States entered the First World War, membership in the NACW had grown to an extraordinary 300,000 nationwide.”

“From 1898 to 1902 Wells-Barnett served as secretary of the National Afro-American Council, and in 1910 she founded and became the first president of the Negro Fellowship League, which aided newly arrived migrants from the South.” “A typical local black suffragist initiative was the organization of the Alpha Suffrage Club in Chicago by Ida Wells Barnett in 1910″ and Chicago’s Alpha Suffrage Club “may have been the first black woman suffrage group”, although several sources say it was the first black women suffrage group. This was founded “after women there [in Chicago] were granted the right to vote in local elections. The first effort of this club was the promotion of the candidacy of an African American as alderman. Later, the club worked against the campaign of white women in Illinois to pass a restricted suffrage proposal that would bar black women from voting.”

“In 1906, [Ida] joined with William E.B. DuBois and others to further the Niagara Movement”. “After brutal assaults on the African-American community in Springfield, Illinois, in 1908, Wells sought to take action: The following year, she attended a special conference for the organization that would later become known as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.” “Wells-Barnett took part in the 1909 meeting of the Niagara Movement and the founding of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) that sprang from it.” “[S]he was one of two African American women to sign ‘the call’ to form the NAACP in 1909.” “Although she was initially left off the NAACP’s controlling Committee of Forty, Wells-Barnett later became a member of the organization’s executive committee”. Despite being one of the NAACP’s founding members, Ida B. Wells “was also among the few Black leaders to explicitly oppose Booker T. Washington and his strategies. As a result, she was viewed as one the most radical of the so-called ‘radicals’ who organized the NAACP and marginalized from positions within its leadership.” “Wells later cut ties with the organization; she explained her decision thereafter, stating that she felt the organization—in its infacy [sic] at the time she left—had lacked action-based initiatives.”

“From 1913 to 1916, [Ida] served as a probation officer of the Chicago municipal court. She was militant in her demand for justice for African Americans and in her insistence that it was to be won by their own efforts.”

“On March 3, 1913, as 5,000 women prepared to parade through President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration, demanding the right to vote, Ida B. Wells was standing to the side…[A] few days earlier, leaders of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) had insisted she not march with the Illinois delegation. Certain Southern women, they said, had threatened to pull out if a black woman marched alongside whites.

Didn’t black women have as much right to vote as white women? Sixty-five years earlier, at the dawn of the woman’s suffrage movement, most suffragists would have said yes. In fact, early feminists were often anti-slavery activists before they started arguing for women’s rights. In the fight for civil rights, they encountered male abolition leaders who ordered them not to speak in public. And the parallels between black slaves — who could not vote or hold property — and women — who could do neither in most states — couldn’t be ignored. As abolitionist Angelina Grimke recalled, ‘The investigation of the rights of the slave has led me to a better understanding of my own.'”

“By 1900, most suffragists had lost their enthusiasm for civil rights, and actually used racism to push for the vote. Anna Howard Shaw, head of NAWSA, said it was ‘humiliating’ that black men could vote while well-bred white women could not. Other suffragists scrambled to reassure white Southerners that white women outnumbered male blacks in the South. If women got the vote, they argued, they would help preserve ‘white supremacy’.”

“According to Catherine H. Palczewski, a professor of women’s and gender studies at the University of Northern Iowa, after the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, a “racist component” of the suffrage campaign ensued. Suffragists Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony did not support black male suffrage unless women also had the right to vote. “’I will cut off this right arm of mine before I will ever work or demand the ballot for the Negro and not the woman,’ [Susan B. ]Anthony once said”.

As pointed out by Mary Walton, ‘Everyone was welcome to participate, including men, with one exception. In a city that was Southern in both location and outlook, where the Christmas Eve rape of a government clerk by a black man had fanned racist sentiments, [Alice] Paul, a white woman, was convinced that other white women would not march with black women. In response to several inquiries, she had quietly discouraged blacks from participating. She confided her fears to a sympathetic editor: ‘As far as I can see, we must have a white procession, or a Negro procession, or no procession at all.’”

“So, despite the fact that the right to vote was no less important to black women than it was to black men and white women, African American women were told to march at the back of the parade with a black procession. Despite all of this, the 22 founders of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority marched. It was the only African American women’s organization to participate. The group was founded on Jan. 13, 1913, at Howard University, and its contribution to the Washington’s Women’s Suffrage Parade was the founders’ first public act. Mary Church Terrell was an honorary member of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority who marched with the women under their banner. The daughter of former slaves, Terrell was one of the founders of the National Association of Colored Women… Ida B. Wells-Barnett, another member of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, marched. “When the Illinois procession instructed Wells-Barnett of the edict that she march with an all-black delegation, she ‘refused to take part unless ‘I can march under the Illinois banner.’ And so she did, walking between two white supporters in the Illinois delegation.”

Now, it should be noted that “[n]ot all white women took the segregationist position to heart. Just as Lucy Stone sided with Douglass, Ida Wells Barnett actively organized along with her white colleague, Viola Belle Squire.

In Ida B. Wells-Barnett and American Reform, 1880-1930, author Patricia A. Schechter reports:

‘In an event that showcased her media instincts, Wells-Barnett protested the jim-crowing of African American women to the back of a major pro-woman-suffrage parade held in Washington, D.C., in March 1913. The parade was a national event that drew thousands of women from across the country. Several white women from the Illinois suffrage delegation supported Wells-Barnett’s anti-segregation position at the parade. During the women’s confrontation with parade organizers, a reporter caught Wells-Barnett talking through tears. The Chicago Tribune described a Plea by Mrs. Barnett in which her voice trembled with emotion and two large tears coursed their way down her cheeks before she could raise her veil and wipe them away. The Illinois women lost their protest, but Wells-Barnett, ever the astute judge of a political and theatrical moment, devised another plan. On parade day, she stepped from the sidelines to join the Illinois delegation at the head of the procession. This dramatic gesture required not just confidence in her colleagues’ support (the Illinois women did not know of her plan ahead of time) but also personal courage.’” (emphasis added)

“Working on behalf of all women, Wells, as part of her work with the National Equal Rights League, called for President Woodrow Wilson to put an end to discriminatory hiring practices for government jobs. She created the first African-American kindergarten in her community and fought for women’s suffrage.”

“[In] 1930, she became disgusted by the nominees of the major parties to the state legislature, so Wells-Barnett decided to run for the Illinois State legislature, which made her one of the first Black women to run for public office in the United States.”

“Health problems plagued her the following year. Ida B. Wells died of kidney disease on March 25, 1931, at the age of 68, in Chicago, Illinois… With her writings, speeches and protests, Wells fought against prejudice, no matter what potential dangers she faced. She once said, ‘I felt that one had better die fighting against injustice than to die like a dog or a rat in a trap.’”