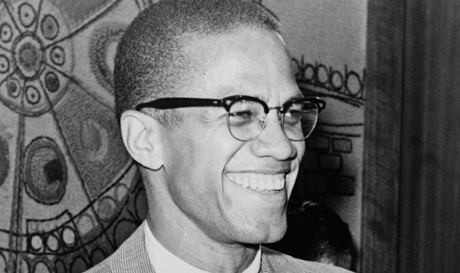

Malcolm X

[From The Archives]

The following is a speech by Malcolm X speech from 1965 about how the colonial misrepresentation of Africa created inferiority complexes and hatred towards Africa in the Diaspora African communities. He was assassinated on February 21, 1965.

Why should the Black man in America concern himself since he’s been away from the African continent for three or four hundred years? Why should we concern ourselves?

What impact does what happens to them have upon us? Number one, you have to realize that up until 1959 Africa was dominated by the colonial powers. Having complete control over Africa, the colonial powers of Europe projected the image of Africa negatively.

They always project Africa in a negative light: jungle savages, cannibals, nothing civilized. Why then, naturally it was so negative that it was negative to you and me, and you and I began to hate it. We didn’t want anybody telling us anything about Africa, much less calling us Africans.

In hating Africa and in hating the Africans, we ended up hating ourselves, without even realizing it. Because you can’t hate the roots of a tree, and not hate the tree. You can’t hate your origin and not end up hating yourself. You can’t hate Africa and not hate yourself.

You show me one of these people over here who has been thoroughly brainwashed and has a negative attitude toward Africa, and I’ll show you one who has a negative attitude toward himself. You can’t have a positive toward yourself and a negative attitude toward Africa at the same time. To the same degree that your understanding of and attitude toward become positive, you’ll find that your understanding of and your toward yourself will also become positive.

And this is what the white man knows. So they very skillfully make you and me hate our African identity, our African characteristics. You know yourself that we have been a people who hated our African characteristics. We hated our heads, we hated the shape of our nose, we wanted one of those long doglike noses, you know; we hated the color of our skin, hated the blood of Africa that was in our veins. And in hating our features and our skin and our blood, why, we had to end up hating ourselves. And we hated ourselves.

Our color became to us a chain–we felt that it was holding us back; our color became to us like a prison which we felt was keeping us confined, not letting us go this way or that way. We felt all of these restrictions were based solely upon our color, and the psychological reaction to that would have to be that as long as we felt imprisoned or chained or trapped by Black skin, Black features, and Black blood, that skin and those features and that blood holding us back automatically had to become hateful to us. And it became hateful to us.

It made us feel inferior; it made us feel inadequate made us feel helpless. And when we fell victims to this feeling of inadequacy or inferiority or helplessness, we turned to somebody else to show us the way. We didn’t have confidence in another Black man to show us the way, or Black people to show us the way. In those days we didn’t. We didn’t think a man could do anything except play some horns–you know, make sound and make you happy with some songs and in that way.

But in serious things, where our food, clothing, shelter, and education were concerned, we turned to the man. We never thought in terms of bringing these things into existence for ourselves, we never thought in terms of doing for ourselves. Because we felt helpless.

What made us feel helpless was our hatred for ourselves. And our hatred for ourselves stemmed from hatred for things African. After 1959 the spirit of African nationalism was fanned to a high flame, and we then began to witness the complete collapse of colonialism. France began to get out of French West Africa, Belgium began to make moves to get out of the Congo, Britain began to make moves to get out of Kenya, Tanganyika, Uganda, Nigeria, and some of these other places.

And although it looked like they were getting out, they pulled a trick that was colossal. When you’re playing ball and they’ve got you trapped, you don’t throw the ball away–you throw it to one of your teammates who’s in the clear. And this is what the European powers did.

They were trapped African continent, they couldn’t stay there –they were looked upon as colonial and imperialist. They had to pass the ball to someone whose image was different, and they passed the ball to Uncle Sam. And he picked it up and has been running it for a touchdown ever since.

He was in the clear, he was not looked upon as one who had colonized the African continent. At that time, the Africans couldn’t see that though the Unites States hadn’t colonized the African continent, it had colonized twenty-two million Blacks here on this continent. Because we’re just as thoroughly colonized as anybody else. When the ball was passed to the United States, it was passed at the time when John Kennedy came into power. He picked it up and helped to run it. He was one of the shrewdest backfield runners that history has recorded. He surrounded himself with intellectuals–highly educated, learned, and well informed people.

And their analysis told him that the government of America was confronted with a new problem. And this new problem stemmed from the fact that Africans were now awakened, they were enlightened, they were fearless, they would fight. This meant that the Western powers couldn’t stay there by force. Since their own economy, the European economy and the American economy was based upon their continued influence over the African continent, they had to find some means of staying there.

So they used the friendly approach. They switched from the old, openly colonial imperialistic approach to the benevolent approach. They came up with some benevolent colonialism, philanthropic colonialism, humanitarianism, or dollarism. Immediately everything was Peace Corps, Operation Crossroads, “We’ve got to help our African brothers.” Pick up on that: Can’t help us in Mississippi. Can’t help us in Alabama, or Detroit, or out here in Dearborn, where some real Ku Klux Klan lives. They’re going to send all the way to Africa to help.

One of the things that made the Black Muslim movement grow was its emphasis upon things African. This was the secret to the growth of the Black Muslim movement. African blood, African origin, African culture, African ties. And you’d be surprised–we discovered that deep within the subconscious of the black man in this country, he is still more African than he is American. He thinks that he’s more American than African, because the man is jiving him, the man is brainwashing him every day.

He’s telling him, “You’re an American, you’re an American.” Man, how could you think you’re an American when you haven’t ever had any kind of an American treat over here? You have never, never. Ten men can be at a table eating, you know, dining, and I can come and sit down where they’re dining. They’re dining; I’ve got a plate in front of me, but nothing is on it. Because all of us are sitting at the same table, are all us are diners? I’m not a diner until you let me dine. Just being at the table with others who are dining doesn’t make me a diner, and this is what you’ve got to get in your head here in this country. Just because you’re in this country doesn’t make you an American.

No, you’ve got to go farther than that before you can become an American. You’ve got to enjoy the fruits of Americanism. You haven’t enjoyed those fruits. You’ve enjoyed the thorns. You’ve enjoyed the thistles. But you have not enjoyed the fruits, no sir. You have fought harder for the fruits the white man has, you have worked harder for the fruits than the white man has, but you’ve enjoyed less. When the man put the uniform on and sent you abroad, you fought harder than they did. Yes, I know you–when you’re fighting for them, you can fight.

The Black Muslim movement did make that contribution. They made the whole civil rights movement become more militant and more acceptable to the white power structure. He would rather have them than us. In fact, I think we forced many of the civil rights leaders to be even more militant than they intended. I know some of them who get out there and “boom, boom, boom” and don’t mean it. Because they’re right on back in their corner as soon as the action comes.

The worst thing the white man can do to himself is to take one of these kinds of Negroes and ask him, “How do your people feel, boy?” He’s going to tell that man that we are satisfied. That’s what they do, brothers and sisters. They get behind the door and tell the white man we’re satisfied. “Just keep on keeping me up here in front of them, boss, and I’ll keep them behind you.” That’s what they talk when they’re behind closed us. Because, you see, the white man doesn’t go along with anybody who’s not for him. He doesn’t care are you for right or wrong; he wants to know are you for him. And if you’re for him, he doesn’t care what else you’re for. As long as you’re for him, then he puts you up over the Negro community. You become a spokesman…

Brothers and sisters, let me tell you, I spend my time out there streets with people, all kinds of people, listening to what they have to say. And they’re dissatisfied, they’re disillusioned, they’re fed up, they’re getting to the point of frustration where they begin to feel, “What do we have to lose?” When you get to that point, you’re the type of person who can create a very dangerously explosive atmosphere. This is what’s happening in our neighborhoods, to our people.

I read in a poll taken by Newsweek magazine this week, saying that Negroes are satisfied. Oh, yes, Newsweek, you know, supposed to be a top magazine with a top pollster, talking about how satisfied Negroes are. Maybe I haven’t met the Negroes he met. Because I know he hasn’t met the ones that I’ve met. And this is dangerous. This is where the white man does himself the most harm. He invents statistics to create an image thinking that that image is going to hold things in check.

You know why they always say Negroes are lazy? Because they want Negroes to be lazy. They always say Negroes can’t unite, because they don’t want Negroes to unite. And once they put this thing in the Negro’s mind, they feel he tries to fulfill their image. If they say you can’t unite Black people and then you come to them to unite them, they won’t unite, because it’s been said that they’re not supposed to unite. It’s a psycho that they work and it’s the same way with these statistics.

When they think that an explosive era is coming up, then they grab their press again and begin to shower the Negro public, to make it appear that all Negroes are satisfied. Because if you know you’re dissatisfied all by yourself and ten others aren’t, you play it cool; but if you know that all ten of you are dissatisfied, you get with it. This is what the man knows. The man knows that if these Negroes find out how dissatisfied they really are–even Uncle Tom is dissatisfied, he’s just playing his part for now–this is what makes the man frightened. It frightens them in France and it frightens them in England, and it frightens them in the United States.

And it is for this reason that it is so important for you and me to start organizing among ourselves, intelligently, and try to find out: “What are we going to do if this happens, that happens or the next thing happens?” Don’t think that you’re going to run to the man and say, “Look, boss this is me.” Why, when the deal goes down, you’ll look just like me in his eyesight; I’ll make it tough for you. Yes, when the deal goes down, he doesn’t look at you in any better light than he looks at me…

I say again that I’m not a racist, I don’t believe in any form of segregation or anything like that. I’m for brotherhood for everybody, but I don’t believe in forcing brotherhood upon people who done’ want it. Let us practice brotherhood among ourselves, and then if others want to practice brotherhood with us, we’re for practicing it with them also. But I don’t think that we should run around trying to love somebody who doesn’t love us.