By Dr. Brooks Robinson\BlackEconomics.org

Photos: YouTube Screenshots

A well-known saying is: “All politics is local.” However, there is no comparable saying for economics or commerce. Given that we are all cognizant of the political economy’s importance, we suggest: “All economics/commerce is personal.”

As Black (Afrodescendant) Americans, we are concerned with inequality, which is a political economy issue. We are trained or programmed to emphasize income- and wealth-inequality. For the latter, we consider our holdings of financial and non-financial wealth. Unfortunately, we do not emphasize our health (“our health is our wealth”) or our cultural/social capital that is produced by our environment and serves as a very important partial determinant of certain life outcomes.

Let us not forget that, as Prof. Maulana Ron Karenga (the Father of Kwanzaa) reminds us: “We do not live in the middle of the air…we live in a definite social and historical context.”[1] Here, “definite” can be interpreted to mean our physical environments. Therefore, why do we not emphasize our right to physical environments (areas of influence, neighborhoods, or communities)

that are equal?[2]

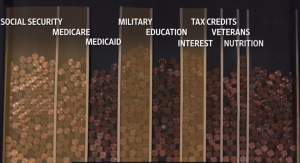

Turning now to income-earning opportunities in the public sector where we are over-represented, we demand and claim our right to employment (at all three government levels) based on our population representativeness. Therefore, it is inconsistent and troubling that we have not been as vociferous in demanding and claiming our right to non-compensation expenditures at all levels of government.

The opposition will say: But you (Black people) do not pay a representative share of taxes. This may be true at the federal and state levels because our wage and salary, entrepreneurial, and property incomes—due in large measure to racial discrimination—are generally lower than most other racial or ethnic groups.[3] But we should explore further whether this is true at the local (county and

municipal) level.

The argument goes: Black Americans reflect limited ownership of non-financial assets on which property taxes are paid; consequently, we have a limited basis for demanding that tax revenues be expended to improve and upkeep our areas of influence.[4] This argument appears to convey racial discriminatory sentiments that are based on a very strict legal (not economic) interpretation of

reality. A logical and reasonable response from a purely economic perspective is that, while Black American (and other) residents may not “own” certain residential and nonresidential real estate and do not pay related property taxes directly, the taxes paid on the property we inhabit are passed on to us and are embodied in our lease payments.[5]

Also, there is another argument favoring Black Americans and others with relatively low incomes. General sales and excise taxes are viewed widely as “regressive,” and important consumption goods and services reflect income inelasticity.[6] Hence, it is possible that we may pay a more than representative share of these taxes.

A broader argument by the opposition might be that residents agree to enter a social contract where revenues are pooled and expended to provide for all residents’ general well-being and in all residents’ best interests. The counter argument is that, too often, the bodies elected or selected to determine what is in residents’ best interest and for their well-being are controlled by non-Black American groups that set agendas and approve policy actions because they constitute simple- or supra-majorities. This despite our “fair” representation within these bodies.

The fundamental question before us is: Should we (Black Americans) remain bound to political and social arrangements that only consider fair legal and political principles that violate—sometimes egregiously—fair economic principles and produce unfair economic outcomes? This question is particularly poignant when those in control have a long, storied, and horrid history as our

opposers.

The foregoing is not a case of “taxation without representation.” Rather it is a case of “taxation without receiving an economically fair share of benefits derivable from

total expenditures.”

As you attempt to gather evidence concerning this topic, you may find that local governments have not tabulated historically, and do not tabulate now, tax and other revenue and expenditures by government geographical areas or subdivisions. These governments are likely to report that they have no easy way of reporting historical differences in revenues collected and expended for affluent areas within your county/city that are typically occupied by White elites versus less affluent areas where most Black Americans reside.

Our suggestion is that Black Americans organize and demand a line item within local governments’ budgets that enables retabulations of government revenues and non-compensation operational and capital expenditures by agreed geographical areas or subdivisions—without regard to legal ownership.[7] At a minimum, this work should encompass the most recent 10-years (or for the period that such records are available). [Also, consider demanding that Black-owned information technology and related firms are approved to help perform this work, which will primarily involve: Electronic scanning of tax payments, invoices, work orders, and other fiscal documents; mapping these documents to geographical subdivisions; and preparing tabulations of the documents

(revenues and expenditures) by geographical subdivisions.]

Once the data are in hand (you should accept little-to-no delay in obtaining them), let them speak for themselves. Realize that three-to-five-or-more-year-trend averages should be scrutinized to identify unfair racial discriminatory revenue and expenditure practices that help produce economic inequality. When such a view crystalizes, then commence negotiations to address the inequality. If governments are unwilling to negotiate economically-just agreements, then consider alternatives.

As an example of a planning tool that can help develop a path to realistic and practical alternatives, we offer the Long-Term Strategic Plan for Black America.

Dr. Brooks Robinson is the founder of the BlackEconomics.org website.

References:

[1] The quote is from “The Literary Corner: Ron Karenga’s Life and Works.” (1978) The Literary Corner. The National Museum of African American History and Culture. https:/nmaahc.si.eduobject/nmaahc_2010.17.1.8a (Ret. 021524). The quote begins at the 6:40 mark of the recording.

[2] As an aside, it is prudent that we examine our call for “equality” by asking: Equal to whom and why?

[3] Brooks Robinson (2022). “Black American Taxes: Comparing What We Pay.” BlackEconomics.org. April 15th. https://www.blackeconomics.org/BELit/batcwwp.pdf (Ret. 021524).

[4] It is common knowledge that Black American home and business ownership rates are substantially below those of other racial ethic groups—especially White Americans.

[5] This perspective is consistent with accounting standards that assign economic ownership of non-financial assets under long-term (capital/financial) leases to leasees, as opposed to lessors (actual legal owners).

[6] That is, consumption of certain important goods and services tends to not be widely differentiated along the income spectrum. In other words, low-, medium-,and high-income consumers spend similar amounts on these goods and services and pay similar amounts of taxes.

[7] This will suffice for property taxes and for fees and fines. However, sales and excise taxes must account for Black spending outside of our areas of influence.