[Amy Coney Barrett]

“Trump’s nomination of Amy Coney Barrett…have raised anxieties about a reconfigured court’s impact on our environmental laws. Barrett’s refusal to answer questions on climate change during her confirmation hearings has only increased worries.”

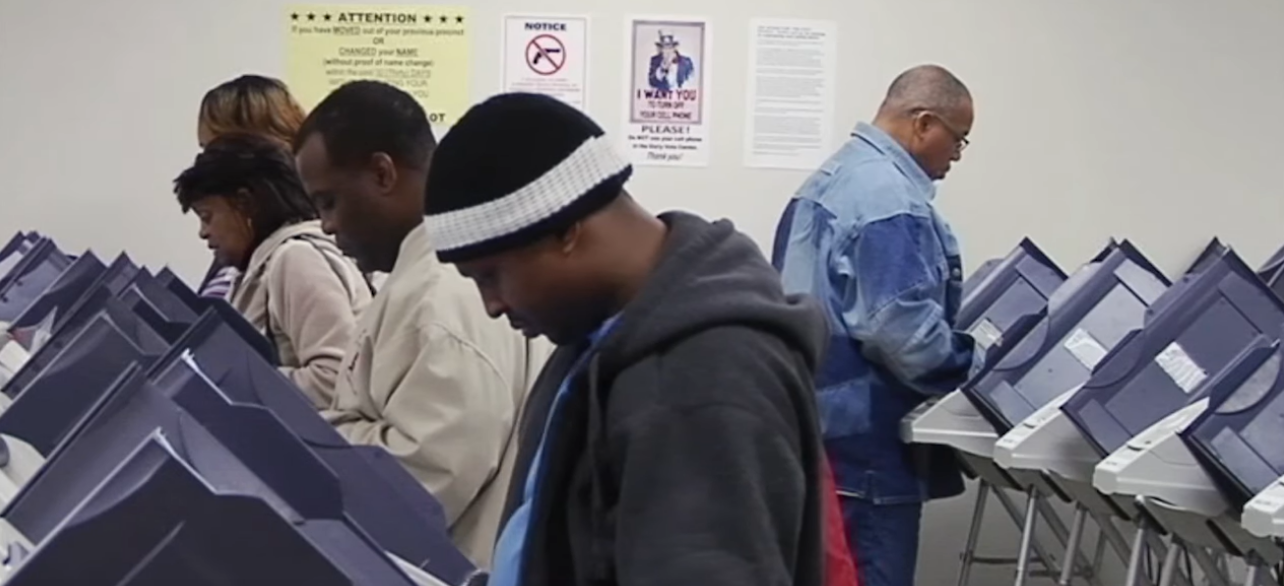

Photo: YouTube screenshot

The following commentary, on the nomination of Judge Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court, was written by Keith Pluymers, Assistant Professor of History at Illinois State University; Sarah Lamdan, a Professor of Law at City University of New York School of Law; and Christopher Sellers, a professor of History at Stony Brook University. They are members of the Environmental Data and Governance Initiative.

The death of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and President Trump’s nomination of Amy Coney Barrett as her successor have raised anxieties about a reconfigured court’s impact on our environmental laws. Barrett’s refusal to answer questions on climate change during her confirmation hearings has only increased worries about the future of climate legislation and environmental protection if she joins the court.

But Ginsburg herself had a more “complex” history on key environmental cases than her green reputation suggests. She joined a bare majority in the 2007 case enabling regulation of greenhouse gas emissions under the Clean Air Act, but also authored a unanimous opinion in 2011 preventing lawsuits against private power companies for their greenhouse gases.

Since the 1970s, the Supreme Court has often proven an unsteady ally or antagonist in environmental protection, even as lower courts supplied many environmental victories. A Barrett confirmation will only add to the Court’s already blunted ability to contend with environmental realities. The best remedies lie beyond the Barrett battle, in Court reform through term-limits or expansion, as well as new laws that can more effectively ensure meaningful climate action.

Like in so many other areas of law, conservative judges have steadily stripped away environmental regulation not so much by blasting apart environmental policy from the top, more from a gradual erosion of its scope and impact. They’ve done so quietly, through court decisions claiming to “limit government intrusion” or overreach, to respect the separation of powers, or to “eliminate red tape.”

That was Justice Antonin Scalia’s playbook: leaning on technical issues like standing (the right to seek redress in court) and the precise nature of an environmental harm to shift the questions at stake from those of fact to those of process. Barrett’s limited environmental jurisprudence suggests that she will do likewise.

Now, with so many Trump Administration actions now winding their way through the federal courts, a still more pro-industry and de-regulatory Court could well turn less quiet and stealthy, cementing far-reaching curtailments of the scope and force of our environmental laws.

The Trump administration’s proposal that National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA) be “modernized” offers a case in point. In early 2020, the Trump administration’s Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) officially curbed NEPA requirements to exclude cumulative or indirect environmental impacts of government projects as well as impacts that are “geographically remote.” Now, when the government builds a highway, it need not assess the potential environmental harm caused by increased traffic and roadside developments. Over twenty environmental groups and many states have already sued over the new NEPA regulations, and the Supreme Court may well be tasked with deciding this case.

Should it be asked to do so the Court’s decision will rest on the decades of Court decisions that have already limited NEPA’s role to merely a “procedural hurdle,” without regard for actual environmental results, abandoning the law’s original transformative vision of, as Adam Sowards argues, a “productive harmony” between humans and the natural environment.

That corrosion was long in coming, actually starting in 1989, when the Supreme Court unanimously decided that NEPA is merely procedural. In 2010, a majority then agreed with Justice Antonin Scalia that agencies could skip NEPA procedures when environmentally risky projects will only cause “possible” and not “likely” irreparable environmental harm. Justice John Paul Stevens, author of the 1989 decision, now dissented, insisting that courts should consider scientific evidence and not solely administrative process. But the die was already cast: accumulating decisions like these had chipped away at environmental governance, slyly constricting environmental policies without overturning the law. The door had opened for an administration like Trump’s to come along, to seek far-reaching dismantlement of bedrock environmental laws.

It is tempting to see a shift from a 5-4 to a 6-3 conservative majority on the Court as an existential threat to environmental protection, but in truth, many of the court’s legal impediments to meaningful environmental action have been building for decades. Environmentalists’ worries about 48 year-old nominee Barrett are indeed justified; yet her arrival on the nation’s highest bench will likely only reinforce the Court’s growing inclination to treat environmental matters as merely administrative and procedural, without regard for the science and substance of what is at stake.

Addressing the already present harms and looming damage from climate change requires more than just contesting one appointment. It demands hard, science-based, and democratic discussions about what a “productive harmony” between people and nature might mean and when environmental protection should supersede considerations of economic growth. Starting with the coming election, we need to elect leaders willing to reform the Supreme Court as an institution, also to broach these difficult questions and craft new laws that provide answers.

Keith Pluymers is Assistant Professor of History at Illinois State University. Sarah Lamdan is a Professor of Law at City University of New York School of Law. Christopher Sellers (@ChrisCSellers) is a professor of History at Stony Brook University. All authors are members of the Environmental Data and Governance Initiative.