Photos: YouTube Screenshots\Wikimedia Commons

For generations, Black and Brown communities have been silenced by systemic racism, our needs and knowledge ignored by entrenched power, our neighborhoods, homes, and bodies subject to violent control and dehumanization. Over the last few years, this dynamic has been clearly visible in the development of the Atlanta Public Safety Training Center, dubbed “Cop City” by opponents.

Last week, however, those opponents made it equally clear that they will not be silenced.

Organizers in Atlanta recently announced that they have collected more than the required 70,000 signatures to place a referendum on the November ballot; the referendum’s goal is to get the city to repeal the ground lease it granted the Training Center. With 80,000 signatures gathered by last week, organizers intended to have 100,000 by today.

This referendum campaign reflects the fact that, from its inception, the plans for the Training Center have depended on obfuscation, disinformation, and disregard for the people in and around Atlanta. In 2021, then-Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms announced plans to build the facility in an unincorporated section of DeKalb County on land once used by the city as a prison farm. Her advisory board consisted of foundation heads, city employees, and police and fire department personnel. There was no community participation.

The proposal required approval by the Atlanta City Council, but given the property’s unincorporated status, residents living next to the proposed training center have no representation on the council. When the city chose to allow public comment on the plan in September 2021, the community delivered 17 hours’ worth of comments; 70% were opposed. The council approved the proposal anyway.

The subsequent years of growing public opposition, criticism, and protest appear not to have swayed current Mayor Andre Dickens, who was the focus of a protest held outside the Atlanta Police Foundation’s headquarters this spring: “Mayor Andre Dickens,” one organizer called through a bullhorn, “is this enough Black folks for you?” In May, hundreds of community members stood in a line that wound through Atlanta City Hall, down the stairs, and out the door, to register their opinion on the Training Center. Every single comment was in opposition.

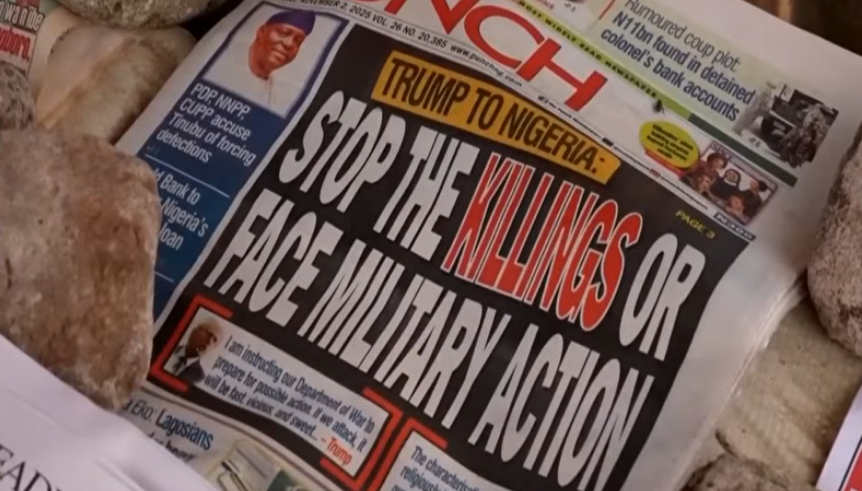

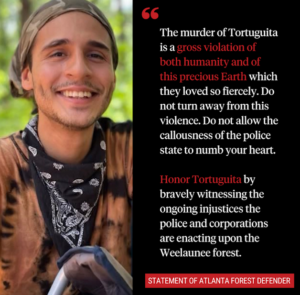

National and international attention to the controversy grew exponentially following the police killing of an environmental activist known as Tortuguita in January. The 26-year-old, who used they/them pronouns, had been camping in a forested area on the site as part of a months-long protest. Georgia law enforcement initially reported that Tortuguita–an avowed pacifist–had fired at law enforcement, leading officers to return fire; however, an autopsy revealed that they had been in a cross-legged position when shot 57 times, and that no gunpowder residue was found on their hands.

There can be no doubt that first responders need both training and training centers; there can also be no doubt that–when designed, implemented, and monitored correctly–training can be a vital tool in decreasing police violence in Black and Brown communities. But the science shows that the best way to improve policing outcomes is not to increase policing’s footprint, but to reduce police interactions through evidence-informed, community-centered, and equitable public safety systems, grounded in public health.

The U.S. already spends more on policing than many nations spend on their militaries; if funding, facilities, and silencing public opinion were all it took, public safety in this country wouldn’t be marked by the gross racial inequities that currently define it.

The utter contempt that officials have shown residents and their concerns mirrors the increasing nationwide threat to our incomplete democracy.

Moreover, questions of policing and public safety in the U.S. are, as they are in Atlanta, bound up in White supremacy’s history and continuing legacy. Black and Brown people have been disparaged, brutalized, and shut out of decision-making concerning our own communities for far too long; we no longer have the time or patience to wait.

The work we do at the Center for Policing Equity (CPE) is grounded in community. We use science to facilitate community-led redesigns of public safety systems in order to make policing less racist, deadly, and omnipresent.

We stand with the people of Atlanta in fierce opposition to the building of the Atlanta Public Safety Training Center. What the people of Georgia need is not to see more of their money going to law enforcement and systems of punishment, but to have their elected officials invest in systems of care that will prevent Black and Brown communities from having to cry out in crisis in the first place.