Last week marked Thanksgiving, the quintessential American holiday. In part, because it belongs to no religion, it is a day that all people can claim as their own to give thanks, in their way. This marked its 150th birthday.

In the midst of the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln set aside Thursday, Nov. 26, as a day of thanks. The previous week he had just delivered the Gettysburg Address declaring a new birth of freedom in the United States, commemorating the bloodiest battle on American soil. At the beginning of the year, he had issued the Emancipation Proclamation, making the flight of slaves in the South to Union battle lines a march to true freedom and giving the Civil War a new meaning. After the defeats of the Army of Northern Virginia at Antietam in 1862 and Gettysburg in 1863, the tide of the war had swung.

Over the past 150 years, the day grew from a day of reverence to be commercialized into marking the beginning of shopping for the Christmas season-a clearly religious holiday also transformed into a commercial spectacle.

Not unlike the battles of 150 years ago, America is today deeply divided. Over the past 40 years, inequality has grown at an increasing rate. The benefits of economic growth continue to concentrate among the top 1 percent. More studies note that the ladder from the bottom to the top is falling apart, and that lack of economic mobility is fracturing us into a nation of “haves” and “have nots.” And with that divide is a great divide in the paradigms we use to make sense of things.

Despite the clear evidence to the contrary, many Americans cling to a belief that America is the land of social mobility and the inequality we see growing is simply the split between the hardworking and the lazy. So, though the Great Recession threw more than 8 million of us out of work, collapsed the values of millions of homes and destroyed the retirement savings of millions more, there are some who deeply believe that storm rained only on the lazy. And they believe that sunshine lies in heaping greater sacrifice from the lazy to the hardworking few who survived, because they believe benefits trickle down off the rich onto the less industrious.

But this too is a form of commercialism. It is a deep belief in the power of the dollar to judge virtue. It leaves us with deep moral hand-wringing on things like who can marry whom-something with spiritual meaning but no dollar value. It does not countenance deep moral discussions about a rich nation that cuts food assistance to the millions who lost jobs because of bad public policy. But to return to American values and moral vision and away from commercialism, at Thanksgiving, we should pause to ask those deeper questions that are not comfortable to the religion of the dollar.

We should ask, “Why is it that Thanksgiving can no longer be a day America has set aside for families to be together?” Is the dollar too important for a nation to give value to family?

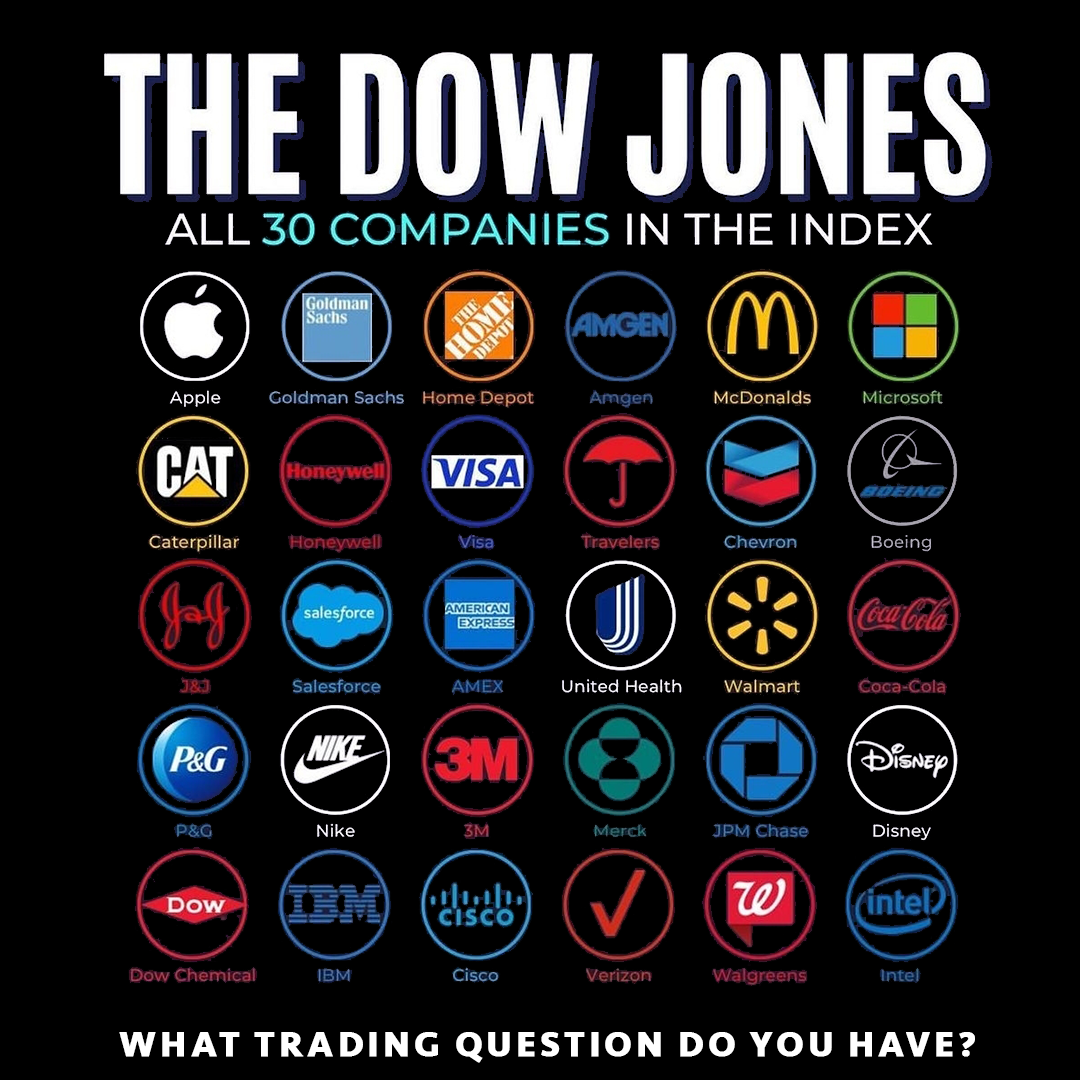

Beyond Thanksgiving Day, can we demand more of a reflection on moral obligations? The largest employer in the United States is Walmart. Last year, Walmart pulled in profits of $17 billion. At its June stockholder meeting, Walmart approved a $15 billion program to buy back its existing shares of stock-a strategy to boost the wealth of current stockholders and consolidate the ownership of the Walton family. Over the past two years, Walmart bought back $14.29 billion in stock-enough to raise the pay of each employee by nearly $5,500 per year. All the while, Walmart’s poorly paid employees rely heavily on federal assistance for health care, housing and food assistance.

So why don’t we have deep debates on why the workers who make Walmart such a large, profitable company need our assistance to buy food, health care or housing assistance?

Around the country Walmart workers are standing up, demanding their fair share of what they contribute to make Walmart so profitable. Their demand for a living wage of $25,000 a year is a demand for fairness and dignity.

There was a time in America when the largest employer was General Motors Co. What does it say about our changing values when we no longer require those with the most to be fair, and only ask those with the least to sacrifice for our prosperity?

Follow Spriggs on Twitter: @WSpriggs. Contact: Amaya Smith-Tune Acting Director, Media Outreach AFL-CIO 202-637-5142