Photos: IBW21.org\YouTube Screenshots\Wikimedia Commons

By Don Rojas

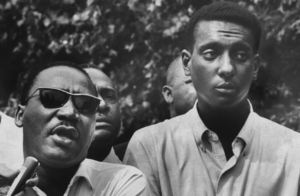

The following speech, written by Pan-African journalist and editor Don Rojas, was prepared to commemorate the life and legacy of of the great Pan-Africanist Kwame Ture at Brooklyn’s House of the Lord Church on July 29, 2023.

Greetings and salutations Sisters and Brothers, Comrades, and friends. It is my pleasure and honor to participate in today’s celebration of the iconic life and legacy of the great revolutionary Pan-Africanist, Bro. Kwame Ture, aka Stokely Carmichael.

With much regret, I’m unable to join you all in person today for reasons of ill health but be assured that my spirit is in your midst. I extend solidarity greetings also on behalf of our dear colleague Dr. Ron Daniels, President of the Institute of the Black World 21st Century (IBW).

Allow me to first thank Rev. Herbert Daughtry, the indomitable senior pastor of the House of the Lord Church, for his kind invitation to be a panelist on this program, and for his determination to keep alive the memory of one of our greatest liberation fighters.

I continue to remain in awe of Rev. Daughtry’s tireless commitment to the liberation of our people both in New York and across the vast African diaspora. Like Kwame Ture did during his lifetime, Rev. Daughtry continues to uphold the principles and ideals of Pan-Africanism. After more than 50 years of fighting in the trenches for peace and justice he continues to fight the good fight today inspiring me and so many others to press on with the struggle, no matter the adversities and setbacks we will encounter along the way.

Black and Brown people in New York and across the world owe Rev. Daughtry a profound debt of gratitude for his steadfastness and consistency in the face of ceaseless exploitation, oppression, and tyranny.

And, on a more personal level, I wish to take this opportunity to publicly thank Rev. Daughtry for inviting me, way back in the late 1970s when I worked as the Brooklyn Editor of the New York Amsterdam News, to cover the activism of his church and that of partnering organizations like the legendary “East” led at that time by our great ancestor Baba Jitu Weusi.

It has been said often that journalism is the first draft of history, and thanks to Rev. Daughtry, I as a journalist became an eyewitness to the making of a significant chapter of global Black history by observing and even participating in the birth of the Black United Front (BUF) in meetings held in the basement of this historic church. I helped to launch a newspaper for the BUF while providing weekly coverage of BUF’s activism in the pages of the Amsterdam News.

Shortly thereafter, I left New York to work for the People’s Revolutionary Government of Grenada, led by Comrade Maurice Bishop. While there, I was assigned to be the Editor of the official newspaper of the Revolution, the “Free West Indian” and later to be press secretary to Prime Minister Bishop. While in Grenada, I was delighted to help organize a solidarity visit to the Spice Isle of representatives from the Black United Front in 1981.

Sisters and Brothers, many of you know about the tragic collapse of the Grenada Revolution, followed by the criminal US imperialist invasion and occupation of sovereign Grenada, so I will not dwell on those fateful events some 40 years ago, except to say on this occasion that the life and legacy of Kwame Ture provided both political lessons and inspiration to all Grenadian revolutionaries back then.

As a fellow son of the Caribbean, who like Stokely Carmichael, migrated to the United States as a youth, I learned much about revolutionary theory and practice from his involvement and leadership in the Civil Rights, Black Power, and Pan-Africanist movements of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s.

For the final 30 years of his remarkable life, Kwame Ture was devoted to the All-African People’s Revolutionary Party (A-APRP). His mentor Kwame Nkrumah had many brilliant ideas for unifying the African continent, and Ture extended the scope of these ideas to the entire African diaspora.

He was instrumental in strengthening ties between the Black liberation movement and several revolutionary or progressive organizations, both African and non-African. Notable among them were the American Indian Movement (AIM) of the United States, the New Jewel Movement (Grenada), National Joint Action Committee (NJAC) of Trinidad and Tobago, Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), the Pan Africanist Congress (South Africa) and the Irish Republican Socialist Party.

While making his home in Guinea in the latter part of his life, Kwame traveled frequently and extensively. In the last quarter of the 20th century, he became the world’s most active and prominent exponent of Pan-Africanism, defined by Nkrumah as “The Liberation and Unification of Africa Under Scientific Socialism”.

He formed the All-African People’s Revolutionary Party (A-APRP) with the initial goal of putting “Africa” on the lips of Black people throughout the diaspora, knowing that many did not consciously or positively relate to their ancestral homeland. Ture was convinced that the party significantly raised international Black “consciousness” of Pan-Africanism. Consequently, the government of his homeland of Trinidad & Tobago barred him from lecturing in the country for fear that he would cause disturbances among Black Trinidadians.

Kwame Ture and Cuban president Fidel Castro admired each other, sharing a common opposition to imperialism. In Ture’s final letter, he wrote:

It was Fidel Castro who before the OLAS (Organization of Latin American States) Conference said, “if imperialism touches one grain of hair on his head, we shall not let the fact pass without retaliation.” It was he, who on his own behalf, asked them all to stay in contact with me when I returned to the United States to offer me protection.

Kwame Ture was ill when he gave his final speech at his alma mater Howard University in Washington, DC. A standing-room-only crowd in Rankin Chapel paid tribute to him, and he spoke boldly, as usual. Also present that evening were Kathleen Cleaver and another Black Panther leader, Dhoruba bin Wahad. Ture was in good spirits though in pain. The crowd included men and women born in Africa, South America, the Caribbean, as well as the USA.

Today, we remember Bro. Kwame for what he called “political modernization.” This idea included three major concepts: “1) questioning old values and institutions of the society; 2) searching for new and different forms of political structure to solve political and economic problems; and 3) broadening the base of political participation to include more people in the decision-making process.” By questioning “old values and institutions”, Kwame was referring not only to the established Black leadership of the time but also to the values and institutions of the United States. He criticized the emphasis on the American “middle-class.” “The values,” he said, “of that class are based on material aggrandizement, not the expansion of humanity.”

Instead, he offered a different vision, one that was influenced by Franz Fanon‘s ideas in The Wretched of the Earth. Kwame often said that U.S. Blacks had to unite and build their power independent of the white structure, or they would never be able to build a coalition that would function for both parties, not just the dominant one.

He said, “we want to establish the grounds on which we feel political coalitions can be viable.” For this to happen, he argued that Blacks had to address three myths regarding coalitions: “that the interests of Black people are identical with the interests of certain liberal, labor, or other reform groups”; that a viable coalition can be created between “the politically and economically secure and the politically and economically insecure”; and that a coalition can be “sustained on a moral, friendly, sentimental basis; by appeals to conscience.” He believed that each of these myths showed the need for two groups to be mutually exclusive, and on relatively equal footing, to be in a viable coalition.

This philosophy, grounded in the independence literature of Africa and Latin America, became the basis for a great deal of Kwame Ture’s work. He fervently believed the Black Power Movement had to be developed outside the white power structure.

Kwame was a strong and vocal critic of the Vietnam War and of imperialism in general. During this period he travelled and lectured extensively throughout the world, visiting Guinea, North Vietnam, China, and Cuba. He became more clearly identified with the Black Panther Party as its “Honorary Prime Minister.” During this period, he acted more as a speaker than an organizer, traveling throughout the country and internationally advocating for his vision of Black Power.

Ture lamented the 1967 execution of the iconic revolutionary Che Guevara, saying:

“The death of Che Guevara places a responsibility on all revolutionaries of the World to redouble their decision to fight on to the final defeat of Imperialism. That is why in essence Che Guevara is not dead, his ideas are with us.”

Kwame visited the United Kingdom in July 1967 to attend the “Dialectics of Liberation” conference. After recordings of his speeches were released by the organizers, he was banned from re-entering Britain. In August 1967, a Cuban government magazine reported that Kwame met with Fidel Castro for three days which Kwame described as “the most educational, most interesting, and the best apprenticeship of [my] public life.”

Because relations with Cuba were prohibited at the time, after his return to the US, the US government withdrew his passport. In December 1967, he traveled to France to attend an antiwar rally. There he was detained by police and ordered to leave the next day, but government officials eventually intervened and allowed him to stay.

Ture, along with Charles V. Hamilton, is credited with coining the phrase “institutional racism“, defined as racism that occurs through institutions such as public bodies and corporations, including universities. In the late 1960s, Ture defined “institutional racism” as “the collective failure of an organization to provide an appropriate and professional service to people because of their color, culture or ethnic origin”.

Historian Peniel Joseph, in his 2014 biography, Stokely: A Life, credits Kwame Ture with expanding the parameters of the civil rights movement, asserting that his Black power strategy “didn’t disrupt the civil rights movement. Rather, it spoke truth to power to what so many millions of young people were feeling. It actually cast a light on people who were in prisons, people who were welfare rights activists, tenants’ rights activists, and also in the international arena.”

In 2002, the American-born scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed Ture as one of his 100 Greatest African Americans.

Throughout his life, he remained a staunch and uncompromising anti-imperialist and I believe that if he were alive today, he would have supported and be engaged with the global reparations movement which is an important 21st Century expression of both anti-imperialism and Pan-Africanism.

In conclusion, we gather today to celebrate a life well lived, to pay tribute to a noble warrior for our people and an exemplar of a principled and consistent servant leader. He has left a magnificent legacy for us to study, admire and emulate.

Finally, for those of us who love and respect Rev. Herbert Daughtry, this visionary and ageless 93-year-old warrior, we say thanks again for celebrating our Bother and Comrade Kwame Ture. Over several decades, you and your family have grown the House of the Lord Church into both a revered place of worship and a veritable Mecca of the Movement for racial and social justice in New York City. For us, you will always remain the unofficial President of the People’s Republic of Central Brooklyn. May God and the Ancestors bless you with good health in the years to come.

Long Live the memory of Kwame Ture…