Before attending a dinner with a business associate one evening, Melissa Pressley went to her office and opened the door to find a flood of documents all over the floor and on the tray attached to the facsimile machine. Had someone broken in? To Pressley, the disheveled condition of the office looked like a scene from an action spy thriller.

Although it was not a break-in, she says, it was the result of one of the “incidents of stalking and harassment” Pressley has faced since she filed a civil suit against the City of New York; she had been forced from her job in 2007.

Named in the suit is Michael Cardozo, the City’s top lawyer, until the recent election of the new mayor, Bill de Blasio, who was sworn in on January 1.

Other defendants in the ongoing case are: Georgia Pestana, Kenneth Majerus , Muriel Goode-Trufant, Stuart Smith, Fay Leoussis, Mark Palomino, Judith Davidow, Marc Andes, Elizabeth Gallay, Inga Van Eysden, Eric Rundbaken, Rita D. Dumain, Gail Rubin, Gabriel Taussig, Foster Mills. All are employed at New York City’s Office of Corporation Counsel (OCC).

The presiding judge in the Eastern District Court of New York is Magistrate Judge Ramon E. Reyes, Jr.

De Blasio has appointed a new Corporation Counsel, the respected African American lawyer and former U.S. Attorney Zachary Carter. It’s unclear if this will change the outcome of Pressley’s case or address some of the inconvenient truths unearthed by Pressley’s lawsuit.

While not offering a breakdown of the number of African American lawyers, even the figures provided by OCC for this article shows that a mere 20% –collectively– of the nearly 700 lawyers in the Office of the Corporation Counsel are Black, Latino and Asian.

Pressley is keen to see how her case, which essentially boils down to challenging the lack of diversity at the OCC, will be handled with Carter at the helm.

When Pressley, formerly a lawyer working in the Special Litigation Unit (SLU) of the Office of Corporation Counsel, filed her discrimination suit against the city of New York, Cardozo and the 15 others hired the prestigious private international law firm Littler Mendelson to represent them. Littler Mendelson assigned has assigned four attorneys one the case during the course of this litigation; three have been assigned simultaneously to litigate against Pressley.

The firm on its website boasts 1,000 lawyers at 60 different locations.

Who is Melissa Pressley and why is the Special Litigation Unit (SLU) willing to spare no expense to deny the accusations in her suit? An expense shouldered by the taxpayer’s of New York City.

Pressley, an African-American woman, answered an ad, was hired and, according to her, after her interview they suggested she join the SLU, which she did on March 1, 2004.

When asked how she felt about being hired, she said: “I had a history of public service and thought this would be a good way to serve the people of New York. I was excited and felt honored.”

Ten years later Pressley is seeking redress for what she says was continuous racial and religious discrimination, and retaliation for reporting the discrimination.

In 1964 the Civil Rights Act was passed and a commission composed of five members, appointed by the President, called the Equal Employment Opportunities Commission (EEOC) was created. The statute authorizes the commission to investigate complaints of discrimination in employment.

In 1965 the federal government banned discrimination in federal employment. Federal, state, and local agencies are also required to follow the provisions of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

However the statute says nothing about the retention of those hired. Therefore racist policies and acts, which may be difficult to prove in a court of law, can continue creating a work place that is hostile and inhospitable with gross inequities impacting minorities. If unable to continue under conditions which are harmful to their emotional, mental, and physical well-being victims often feel forced to leave.

Immediately after she arrived at the SLU, Pressley says she was repeatedly told that she would not succeed there, was not ready for SLU, and that the City had made a mistake in assigning her there. According to her, this continued even though she was successfully completing her assigned tasks with reasonable ease and minimal supervision.

When asked by this media company about Ms. Pressley’s work record the OCC said: “We do not comment on employees’ job performance or on pending litigation.”

Pressley says that within her first three months at SLU, Mark Palomino, chief of SLU, attempted to transfer her “indefinitely” to the Brooklyn or Bronx units within the torts division containing the greatest concentration of African-American attorneys.

When she joined, Pressley was the only non-White attorney in the SLU. There were two African American female attorneys who joined the unit after Pressley’s arrival, who later transferred to other Torts units. The only attorneys who had transferred to other Torts Units from of SLU with promotions or raises during her tenure were White attorneys, she says.

Pressley’s suit states that the City hires African-American attorneys to boost its diversity statistics and then concentrates them mostly in units or divisions handling street offenses while the prestigious or corporate legal units or divisions are overwhelmingly, if not exclusively, assigned to White attorneys.

Career opportunities, promotions, or upward mobility unfairly favors Whites and negatively impacts the retention rate of highly qualified, talented minorities, Pressley says.

The OCC , in response, says: “The most recent statistics reflect 138 attorneys who self-identify as Black, Hispanic, or Asian, out of 680 attorneys. Attorneys in the aforementioned categories make up 20.3 percent of the attorneys in the office, which is in line with the diversity of recent law school graduating classes and much more diverse than the legal profession as a whole.”

(In terms of the proportion of New York City’s citizens, Blacks, Latinos, and Asians make up 64.4% according to the 2010 Census).

During Pressley’s tenure at SLU, she says there were no racial minority supervisors or senior counsel assigned to the unit and there were no racial minority attorneys at the City’s top executive level. The exception is the EEO officer, a position Pressley says is stereotypically given to someone of color. The EEO officer reports to Michael Cardozo.

As New York’s corporation counsel, Cardozo served as the City’s top lawyer and the man who represented the city when it sued, or when the City was sued.

Some things in Cardozo’s work record are revealing.

In the past, Cardozo was on the defensive over arrests made during the 2004 Republican National Convention, when he defended “the city’s methods and motives in detaining hundreds of protesters, well beyond the ordinary legal time limit of 24 hours, without the usual access to lawyers.” In that case Cardozo was reported by the New York Times, as saying that he believed state law gave the city the right to an automatic stay of State Supreme Court judge, Emily Jane Goodman’s order requiring the city to allow defense lawyers to meet their clients “forthwith.”

Cardozo also made a statement leaning towards the police officers who killed Sean Bell; the unarmed victim who was senselessly and fatally shot on the eve of his wedding in November 2006 in a hail of bullets. Cardozo was quoted as saying “The Sean Bell shooting highlighted the complexities our dedicated officers must face each day.”

Cardozo demonstrated no sympathy for Black firefighters who were victorious in a discrimination suit against the Fire Department of the City of New York (FDNY). In a 42-page response, Cardozo blasted the Vulcan Society’s (an organization of Black firefighters) $8.5 million discrimination payout as “unreasonable,” “vague” and “profligate.” He contended that the seven-figure tab was simply too much for taxpayers to pay. The City of New York had for decades discriminated in hiring of African American firefighters.

But perhaps given the composition of the OCC itself Cardozo thought the Vulcan’s case was too close to home.

(Only 2.9% of New York City’s 11,500 firefighters are Black).

His concern for the expenditures in this case is inconsistent, however with his hiring one the best law firms in the city of New York to represent him and his other 15 co-defendants, most of whom are lawyers, against Pressley’s case. She had represented herself, working alone with very limited resources, until she hired a lawyer on November 27, 2013.

Currently, when someone sues — for example– the commissioner at another city agency, that commissioner does not select his own private attorney to defend himself and the city.

The Office of Corporation Counsel handles the defense. However, when one sues Corporation Counsel or the office’s executives, as in Pressley’s case, the OCC selects and directs counsel, for themselves individually, and the City, with discretion over taxpayers’ funds, even though they have a personal and direct financial interest in the outcome of the case.

It appears that there are no checks or balances to prevent malicious or personally abusive use of City funds in litigation when Corporation Counsel is being sued. This alone could discourage someone from pursuing their rights against government officials with unchecked discretion.

The selection of a law firm to represent the City and the individual executives in this action by those individual executives themselves is a conflict of interest.

A protective/confidentiality order proposed by the City and granted by the court, in Pressley’s case, can essentially conceal from the public, the media, and anyone not identified in the order, any information exchanged in discovery, including any possible wrongdoings by top level government officials like Cardozo and how much taxpayer’s money is spent on their defense, that defendants have unilaterally marked as confidential.

“The order does not help to discourage continuing discriminatory practices, because the information concealed cannot generally be used against them in subsequent lawsuits filed by victims,” Pressley says.

Why was it necessary for Cardozo and company to hire a prestigious outside law firm to defend them against one pro se plaintiff?

Pressley first met with head EEO officer, Muriel Goodes-Trufant in December 2004, and thereafter continually until Pressley’s departure in November 2007, she says. Goodes-Trufant, also named as a defendant in the suit, handled Pressley’s internal EEO complaint filed with the City. Pressley’s suit alleges that it was a pattern or practice that when African-American attorneys merely met with the EEO officer to discuss EEO issues for their career advancement or tenure at the City, their careers would be harmed or destroyed.

Retaliation against Pressley began in September 2004 when she refused the repeated demands of her immediate supervisor, Judith Davidow to report to work on Sunday, her Sabbath, she says. She didn’t expect it to be an issue because the offices are closed on weekends, Pressley says. Not until then had there ever been a problem regarding her work schedule.

Pressley told Davidow she couldn’t work Sunday but that she would come in on any other day. Pressley says she completed the pending assignment on time and successfully without coming in on the Sunday but that only a couple of days after that Davidow criticized her—for the first time–in writing for her work arrival times.

Pressley’s first evaluation in 2004, was prepared by Davidow and Mark Palomino and included unfair and untrue comments, ratings, and criticism that implicated her lack of availability on her Sabbath, Pressley says.

The City uses evaluations to prepare subsequent evaluations of an attorney and to make decisions related to transfers, promotions and pay increases, all of which Pressley says have adversely impacted her. Her suit says that in time her conditions deteriorated. The more she communicated with Goodes-Trufant, the EEO officer, the worse conditions became, eventually forcing her to leave, she says.

After leaving the OCC she joined a private law firm that served as outside counsel to the City of New York, Pressley says. Because of pressures from the City, she says, she was dismissed six months later. She began her own law practice but again interference by the City has made things very difficult.

During the course of reporting and writing this article, New York city’s political landscape changed and many observers believe there’s possibility that the OCC could also be transformed.

De Blasio, the new mayor, has already said he plans to settle the case of the five young men who were wrongfully convicted and served long sentences in the so-called Central Park 5 case, a move that’s been widely hailed.

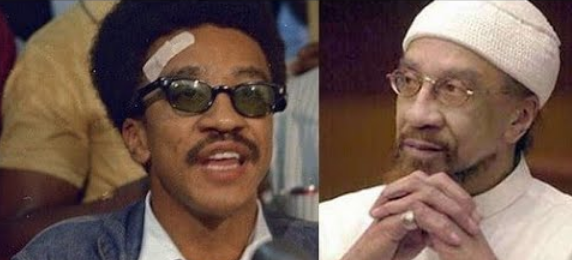

Zachary Carter, a former U.S. Attorney on the Eastern District, is now the City’s Corporation Counsel.

Carter, who is African-American, prosecuted the NYPD officers who beat and sodomized Abner Louima in a Brooklyn police precinct.

Who knows whether the OCC will take a different approach with respect to Pressley’s case. In the meantime, she’s hired legal assistance for her case but it’s still a David vs. Goliath battle, she says.

Even though more and more African-Americans are now graduating from universities, often with high honors, they still encounter road blocks and bigotry in the workplace, as Pressley’s experience shows.

It is evident that the U.S. legal system has changed very little when it comes to the rights of African-Americans and people of color, whether the fight is in the street, the board room or the legal offices of a major city.

Editor’s Note: If you have a similar case to report please reach [email protected]