By Dr. Kevin McGruder

Photos: YouTube Screenshots

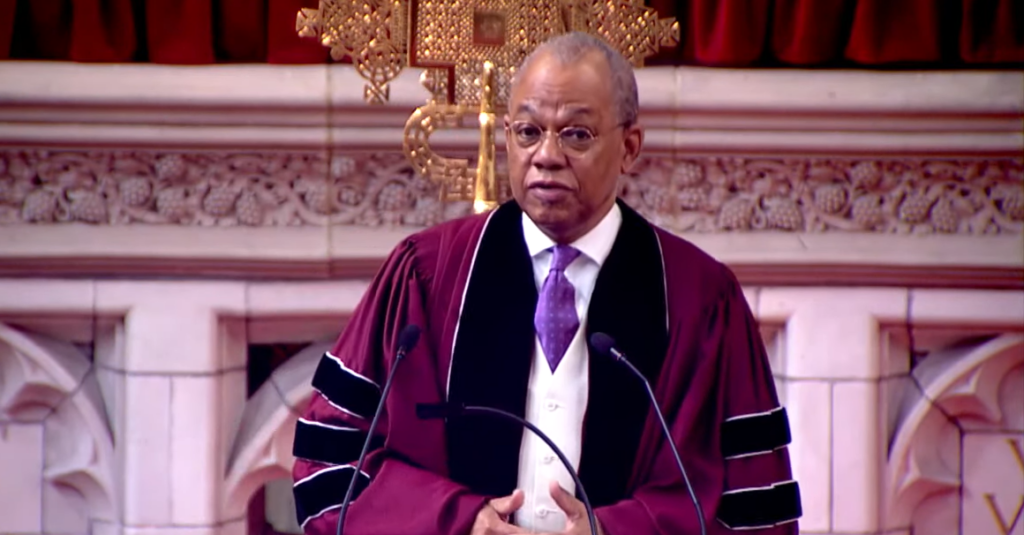

“Do not major in bylaws and minor in the Bible…. America is counting on you, Abyssinian. This is holy ground, not a battleground.” These were remarks made by Rev. Dr. Raphael Warnock at the September 29th installation ceremony for Rev. Kevin R. Johnson, the announced new pastor of the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem. Warnock, as a legislator, advising a congregation to not to ‘major in bylaws’ when electing its new pastor was oddly unusual, particularly at a time when this country was moments away from perhaps the most consequential presidential election in our history. Further, he had been on the frontlines campaigning for the Democratic candidate, Vice President Harris. One of the central Democratic critiques of the first Trump presidency was the fact that he repeatedly broke the law, the rules.

Yet, the Georgia Senator, and former Abyssinian Assistant Pastor, disapprovingly referred to a months-long effort by groups of Abyssinian members to get the church leadership to follow its own rules in selecting a new pastor who would be the successor to Dr. Calvin O. Butts, III, the previous Abyssinian pastor, who died in October of 2022. Our efforts were unsuccessful, largely due to the church leadership’s refusal to adhere to a litany of provisions in the church’s bylaws. In three member-called special meetings, our concerns were ignored and our questions were not answered by church leadership.

The search culminated with the June 23rd announcement of Rev. Johnson as pastor, even though he had received only twenty-five percent of the vote of members rather than the majority required by church bylaws. Why is this so important? When a pastor is called to a church by less than a majority of its members, there is potential danger of a church fracture that could alter the institution’s future, proving detrimental to opportunities for growth and its financial well-being.

Two weeks after the September installation ceremony, the church and Rev. Johnson were served with legal papers in a lawsuit regarding the pastoral search and election. I am one of the four plaintiffs in the suit. I never expected – or wanted – to be in this position. Each of the plaintiffs have varying reasons for being the public face of this effort, which is supported by dozens of other Abyssinian members. For me, my decades-long history with Abyssinian, and my equally long history of working for nonprofit organizations, left me no other choice in taking what I firmly believe is a step toward saving this church that has lost its way as it relates to governance practices. Like any institution or corporation, survival is impossible when its foundation lacks integrity.

Abyssinian is a religious institution. The First Amendment of the Constitution restricts the government from interfering with most aspects of the activities of churches. But Abyssinian is also a nonprofit organization. Like other nonprofits, its exemption from paying income taxes, which also allows its members to deduct our contributions to the church from our personal income taxes, rests on the fact that, like other nonprofit organizations, it is viewed as a public trust, undertaking activities that are for the public good.

Bylaws of nonprofit organizations are the rules that govern their operations. They are developed by the organizations and are expected to be followed, providing organizational consistency as staff and leadership change over the years. They may be amended as needed, but ignoring protocols and bylaws is a sign of serious organizational dysfunction, something that the recent pastoral search and election processes revealed regarding the current governance practices at the Abyssinian Baptist Church that are so egregious that we are asking the court to intervene, after failing to get church leadership to take corrective action.

I became a member of Abyssinian in 1987. I had just turned thirty, and having grown up in the church, had stopped attending regularly as an adult, but felt that something was missing from my life. Abyssinian became a central part of my identity. I was a member of its Chancel Choir, Director of Real Estate Development at the Abyssinian Development Corporation, and led its Archives and History Ministry for over a decade, during which professional archives were established.

My work with the Archives and History Ministry led me to decide to obtain a Ph.D. in U.S. History, and also provided me with the opportunity to become a co-author of the 2014 Abyssinian bicentennial history book, Witness: Two Hundred Years of African American Faith and Practice at the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, New York. I also served as Assistant Church Clerk, one of the officers of the Church, from 2009 to 2012. When I moved to Ohio in 2012, I maintained my Abyssinian membership, supporting the church financially and watching services online. I often traveled to New York for the February annual church meetings.

Abyssinian was founded in 1808 when eleven women and four men of color asked permission to leave the First Baptist Church on Gold Street in Lower Manhattan, a predominantly White congregation. It was the first Black Baptist church established in the state of New York. The 1800s was a period of challenges and small triumphs for Abyssinian, but the church grew and entered the national stage in the twentieth century. Rev. Adam Clayton Powell Sr., pastor from 1908 to 1937, moved the church from midtown to Harlem, and to national prominence through his work with White and Black Progressives of his era.

His son, Rev. Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. succeeded him, and through his concurrent service as the Congressional representative for Harlem, brought the church to international prominence as the “Church of the Masses,” one of the first megachurches with a reported membership of 10,000 people.

After Powell, Jr.’s death in 1972, he was succeeded by Dr. Samuel DeWitt Proctor, who stabilized the church, and then encouraged Abyssinian to be a force for revitalizing its Central Harlem neighborhood by forming the Abyssinian Development Corporation, incorporated in 1989. That same year, Dr. Calvin O. Butts, III succeeded Dr. Proctor as pastor, and continued to build on the foundation that he had inherited. He expanded it in the area of education with establishment of the Thurgood Marshall Academy for Learning and Social Change, a high school and lower school, that are New Vision, smaller public schools.

To appreciate why my fellow petitioners and I have taken these steps, it is important to understand that Abyssinian, a flagship Baptist Church in this country with this rich history, is not merely a church. Abyssinian is often looked to as a model of what could be and what should be as a preeminent institution of faith that has been at the forefront of social justice, equality, and civil rights for the Black community. If Abyssinian’s leadership establishes a dangerous blueprint, with this recent election of a pastor, that ignoring bylaws is acceptable, what type of precedence does this set for the governance of other Black Baptist churches going forward?

Speaking truth and seeking course correction of this matter has had consequences

for me and others. Most recently, at the end of the November 10th Sunday worship service, during which Abyssinian celebrated its 216th anniversary, Rev. Johnson concluded the service by noting that the day before, the Deacon and Trustee Boards had voted unanimously to prohibit any member who was “opposing” the church from continuing to serve in any Abyssinian ministry, the organizations through which most of the day-to-day work of the church is done. Ministries, including choirs and usher boards, are the main vehicles through which members move from Sunday-only attendees to working on activities that strengthen their bonds with other members while creating initiatives that serve Abyssinian and the broader community. Most importantly, as the name implies, serving in an Abyssinian ministry is an opportunity for a member to minister to others like a Christian should.

Rev. Johnson claimed that the recent decision was made at the advice of the church’s attorney, and was meant to achieve “unity” within the church. The statement implies Rev. Johnson and his followers are the “church”. I do not oppose Christ’s church, the congregation of Abyssinian. What I oppose is those who interlope as the church, have a casual disregard for Abyssinian’s bylaws, and show contempt for members of Abyssinian. While I know this latest announcement was meant to isolate and demonize the plaintiffs and others, it was also meant to silence anyone seeking accountability from church leaders, now and in the future, by daring to ask a simple question. It is a page taken out of the playbook of dictators, and it reveals the unethical foundation on which Rev. Johnson and Abyssinian’s church leaders are attempting to build his pastorate that is only a few months old.

Contrary to Rev. Dr. Warnock’s remarks at the recent installation service, I believe that all church members need to be double majors, grounding our faith in our knowledge of the Bible, while also understanding the governance practices, represented in, and the integrity required by, our bylaws. Our lawsuit is meant to provide Abyssinian leadership with an opportunity to embark on a course correction and bring our governance practices, in this case the pastoral search and election process, in alignment with our bylaws so that the Abyssinian Baptist Church in the City of New York can move forward into the future as a well-governed, spiritually strong church. Our goal is to restore integrity at the Abyssinian Baptist Church, something that is now in extremely short supply. To support the Restoring Integrity at Abyssinian Effort, go to: https://gofund.me/9d9f98a5