By Zara Frost

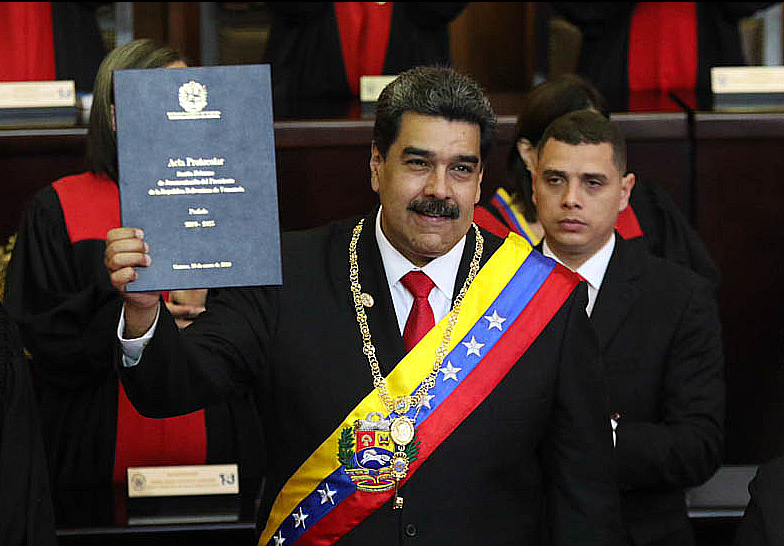

Photos: YouTube Screenshots

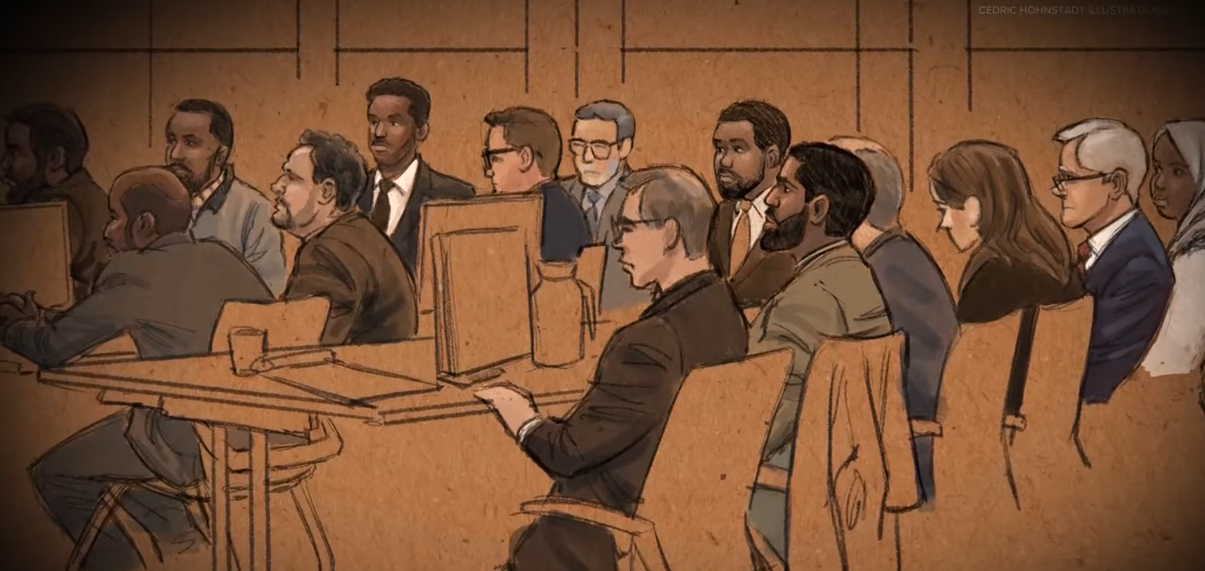

The testimony in the first Feeding Our Future trial, particularly regarding allegedly fraudulent meal rosters, is profoundly flawed and introduced unfair prejudice against the defendants. The government’s approach relies on questionable comparisons and assumptions that fail to reflect the realities of the pandemic and the emergency food distribution system. Let’s explain why this testimony is not probative of wrongdoing and instead misleads the jury.

Comparing School Rosters to Meal Rosters: A Misguided Metric

One of the government’s main arguments centers on comparing meal site rosters to local school attendance records. IRS Special Agent Joshua Parks testified that names on the food site rosters didn’t match students enrolled in nearby schools. But this comparison makes no sense in the context of the pandemic. The meal sites were “open” during COVID-19, meaning families could pick up food from any location, not just the one nearest their home or their child’s school. There were no geographical restrictions.

During the pandemic, the United States Department of Agriculture intentionally expanded access to ensure families could get food regardless of where they lived or whether their children attended local schools. So, the fact that names on the rosters don’t match school records is not evidence of fraud—it reflects the nature of the emergency program rules. The government’s comparison is, at best, a misunderstanding of the program’s design and, at worst, an attempt to skew the evidence to appear more incriminating than it actually is.

No Verification Required: Defendants Are Not Responsible for Government’s Choices

Another glaring issue in the government’s case is the complete disregard for the lack of verification requirements. The federal government waived identification and verification protocols during the pandemic. This was done to ensure families could quickly and easily access food without the usual barriers. The meal sites weren’t expected to check IDs, confirm addresses, or verify enrollment in local schools.

If the government designed the system to operate without these checks, how can it now hold the defendants responsible for any discrepancies in the rosters? The defendants followed the rules of a system built for speed and efficiency, not administrative perfection. The prosecution essentially tries to impose accountability for errors in a system where the government said verification was unnecessary. This argument falls under its own weight when considering the rules the defendants were working under.